|

| The XX Legion set up home in Deva Victrix or modern day Chester |

"By the early years of the second century AD the three legions stationed in Britain were in the fortresses where they were to remain until at least the end of the third century. Legion II Augusta at Isca (Caerleon), Legion VI Victrix at Eboracum (York), where it had replaced IX Hispana, probably at the beginning of Hadrian's reign, and Legion XX Valeria Victrix at Deva (Chester). All three were founded in the seventies of the first century AD."

W.H. Manning 'Roman Fortress Studies' in Deva Victrix (1999)

Our visit to Chester earlier this month adds the third of the Roman fortresses in Britain to be visited following previous visits to Caerleon in 2016 and York last year - see the links below.

As can be seen in the map below, with the subjugation and Romanisation of the south, south-west and midland regions of Britain, the Roman front line was moved north of the first frontier, namely the Fosse Way running from Isca Dumnoniorum (Exeter) in the south west to Lindurn (Lincoln) to establish itself anchored on the three towns that would be the centre of operations for the British legions.

|

| Original map created by Andrei Nacu |

These bases made sense as the Roman commanders pushed out into first Wales and the subjugation of the four tribes (Silures, Ordovices Demetae and Deceangli).

With the north anchored on Deva and Eboracum, the northern tribes were suppressed, although, it seems, probably never fully subjugated; as Agricola under orders from Emperor Vespasian and later his sons Titus and Domitian set out to complete the final occupation of the whole island with the final push into Caledonia, culminating in the Battle of Mons Graupius about 83 AD.

In the end the project to control the whole of Britannia was left incomplete as other areas of the empire drew attention and manpower and then a change of policy to stop further additions to the empire caused a consolidation on the Antonine and later Hadrian's Wall.

|

| Battle of Mons Graupius, Sean O'Brogain - Osprey |

As well as supporting operations in Wales and the north, the establishment of Deva also allowed the Romans the use of a fortress port that may well have been seen as a base to facilitate the projection of Roman power yet further and a possible invasion of Ireland.

|

| The probable appearance of Deva fortress from the 2nd century AD, with the amphitheatre seen on the south-east corner |

The Romans are thought to have established a small fort at Deva as early as 60 AD, however the first legionary fortress with a timber palisade atop an earthen rampart and surrounding ditch was probably built in the 70's AD enclosing an area of some 24 hectares.

The XX Legion Valeria Victrix provided the garrison during most of its occupation but the II Adiutrix may have also been stationed there for a short time as well.

It was in the 2nd century AD that the fortress was rebuilt in the famous local red sandstone as seen in the picture above of the model of the city in the Grosvenor Museum.

The Romans named Deva after the sacred river that flows past it, 'Deva' thought to mean 'goddess' or 'holy one'. Known today as the River Dee, the river still follows a course from the Welsh hills to the Irish Sea, although silt deposits over the intervening centuries have greatly altered its course and depth for ship navigation from the river that the Romans would have known.

It used to be thought that Flavian fortresses were standardised in their layouts and planning but this theory has since been disproved, all be it that the layouts followed a level of standardisation that allows one to work out where particular buildings were likely to be found.

The map above shows how the Roman fortress aligns to the modern city and the extended medieval wall that takes in the original Roman fortification along its north and eastern facing.

Much of the Roman infrastructure of Deva remains hidden under the modern town and a few discoveries are available to be seen in the basements of various shops in the town centre, by prior arrangement.

We confined our tour around the city with visits to places that are readily accessible and then followed that up with a visit to the Grosvenor Museum to see the artifacts that have been discovered over the centuries.

At the centre of a Roman fortress close to the junction of the two roads that connect each of the walls, the Via Principalis (Watergate and Eastgate Streets) the Via Decumana (Northgate Street) and the Via Praetoria (Bridge Street), the Principia (administrative headquarters) has been discovered and in Hamilton Place, just off the Market Square an amazing basement room is visible to passers by in the street.

The strongroom is a massive walled basement room at the back of what would have been the Pricipia built below another room at ground level that would have housed the shrine and statue of the emperor alongside the cohortal and legionary standards when not in the field.

|

| The Principia shrine room with the strongroom below |

The strongroom seen below, under a reconstructed floor level to give a better idea of its position relative to ground level, would have housed the legion's valuables such as the soldiers pay.

In addition to this easily accessed part of the Principia there are also the remains of the cross-hall colonade that was inside the headquarters building in the basement of 23 Northgate Row.

Leaving the centre of the town we headed off down Bridge Street, turning left into Pepper Street to join the wall at Newgate which marks the beginning of the old Roman wall that still remains.

|

| Newgate |

This part of the wall is also a good place to start for the Roman enthusiast as to the right of the gate seen above lies the entrance to the Roman Garden where various pieces of discovered Roman stonework and masonry have been placed for the public to see.

Alongside the garden is also the remains of the amphithetre and across the road are the foundations of the south-east angle tower indicating where the Roman wall originally turned west along Pepper Street to meet up with the lost western wall that ran along the line of St Martin's Way and Nicholas Street.

|

| The mosaic is typically Roman with reference to the four seasons incorporating designs from around the empire |

Turning right into the entrance to the Roman Gardens the visitor is greeted by a Roman style mosaic using designs from north Africa, Vienne in France, Istanbul and an encircling scroll taken from the Woodchester Villa in Gloucestershire.

In Roman times the garden lay outside the south-east corner of the fortress and was a quarry site producing the blocks of red soft sandstone used in the construction of the buildings.

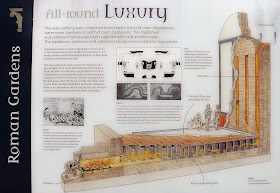

The garden was laid out in 1949 and now serves to display the many Roman building fragments discovered in the city over the previous century, such as the remains of the bath house and columns from the Principia.

The replica hypocaust is based on the remains of the Roman baths first discovered on the east side of Bridge Street near the Via Praetoria South Gate access in 1732.

The remains of the Basilica were later excavated over a hundred years later in 1863 with some of the bases to the pillar columns and a few of the hypocaust pillars can be seen here in the gardens.

However for the more determined visitor, remains in situ are still visible in the medieval rock cut cellar of 39 Bridge Street.

The scale and opulence of these fragments of Roman Chester indicate the stature of the public buildings and the importance of the city in Roman Britain.

The replica black and white mosaics are indicative of the similar patterns discovered in the bath house excavation, part of which is still visible in the basement of the shop at 18 St Micheal's Row.

Some of the sandstone pillars recovered from the basilica are about 2.5 feet in diameter at the base and originally would have been about 11.5 feet in height.

With an arcade above them supporting sloping roofs as in the depiction above, it is estimated that the height of the nave ceiling would have been about 56 feet, a truly imposing building, close to the south wall.

Heading back to the entrance to the garden and turning right leads into the entrance to the Deva amphitheatre.

The amphitheatre's whereabouts was a mystery up until 1929 with the chance discovery by workmen working at a nearby convent school uncovered a piece of curved wall.

Excavations soon followed, led by Professor Robert Newstead who established the northern limits and size of the structure, together with the positions of two entrances.

Work came to a halt with local development plans that unbelievably threatened to build a road right through the site.

A national campaign was started to save the monument which went to the top of government leading the Ministry of Transport to veto the plan, which became world news with reports as far afield as in the New York Times

Large scale excavations took place in the 1960's revealing the remains that can be seen today, with further work done in 2004 to 06 revealing little of the structure has survived but that intriguingly there was originally a much smaller building.

In addition the later work revealed that the first amphitheatre was of stone with wooden seating but that the larger later building was all stone and a much grander affair.

Carolyn and I have visited a couple of other amphitheatres in the UK and I have posted about, with the one at Carleon (see link above) and earlier this year at Cirencester (Corinium Dobunnorum)

The Chester structure seemed much more on a scale with Cirencester, but the revealed walls together with the added modern dressed stones that help illustrate the massive scale of this building have an impact that is not as obvious at Cirencester.

|

| The arena floor surrounded by the area that would have housed the tiered rows of seats above it |

Whilst taking our time to take in the majesty of this amazing building, we came across two members of the Roman Tours Ltd reenactment team who provide knowledgeable guides around the city.

www.romantoursuk.com

Whist talking to the chaps about all things Roman they let me know about their current project to develop a historical park that will faithfully recreate a Roman fort and Iron Age farmstead recreating agricultural techniques and crops from the period very much on the theme of Butser Ancient Farm.

http://jjwargames.blogspot.com/2018/07/butser-ancient-farm-experimental.html

More information about the 'Park in the Past' can be found here.

http://www.parkinthepast.org.uk/

|

| Carolyn's Dumnonii accent gave her away as a stranger to the local garrison |

Close to the arena floor and main entrance was the entrance to the small temple to Nemesis, seen below.

The size of the building that once towered above these remains are hinted at by the thickness of the double circular walls now encased with modern dressed stones that show where the original stonework would have been.

Alongside the massive outer wall, the concrete plinths indicate where a circular row of columns would have been placed on two levels as indicated in the model of the building above.

The role of this building should and cannot be ignored, and it is only emphasised as you walk down the main entrance, which would have been a covered way that would have been much darker to walk along before entering the bright daylight of the arena.

A few of the dressed outer stones are still to be seen and show the marks of the Roman masons.

Towards the centre of the arena close to the wall painted to give an impression of the wider extent of the boundary is the tethering or 'Apprentice Stone' to which combatants or beasts could be tethered during the various contests.

This stone with evidence of a metal ring attached to it was found resting on a plinth of bedrock within about a yard from the centre of the arena and is the strongest possible evidence for gladiatorial combat in Deva.

|

| The Apprentice Stone as depicted in the Bignor mosaic |

Interestingly, I photographed a design from the mosaic at Bignor Villa back in 2016 illustrating such a stone in use with either one or both combatants chained to it.

The Romans in Britain Part Two - Bignor

The other entrance discovered in the early excavations is on the east of the arena and the column fragment at the base of one of its walls is thought to have come from one of the official boxes that would have been built above.

|

| The eastern entrance with the column from the official box |

|

| The entrance to the eastern access point |

Behind the part of the structure that remains fully covered the sections of walls left exposed confirm the size and extent of the whole building.

|

| Wall sections exposed on the part of the building left covered |

Close by were yet more examples of the stonework uncovered in the excavations including the curved stones of a massive arch seen below.

Across the road from the amphitheatre Carolyn and I rejoined the wall at Newgate where we were able to see the remains of the Roman south-east angle tower.

The rather discoloured illustration was taken from the information board and despite the effects of pigeons still gives a good impression of how this tower may have looked with a piece of Roman artillery set up on top and with a twenty foot wide and nine foot deep ditch surrounding its perimeter.

Built sometime between 74 to 96 AD the stone wall would have presented a formidable barrier to the local tribes with any ideas of contesting Roman occupation.

Getting on to the eastern wall we headed north as the path took us among buildings that illustrate the rich and varied past of Chester throughout British history and whilst looking for the Roman sites I was more than aware of the medieval and English Civil War parts that I intend to cover in a later post.

The wall has been rebuilt and modified over the centuries last being put to the test of protecting the inhabitants back in 1745 during the Jacobite Rebellion.

The Roman parts of the wall are more often to be seen at its base as later additions were built over or on top of the original foundations.

The entire Roman fortress went though several rebuilds in its history which seems to come to an end in 125 AD and is thought to correspond with work redirected to Hadrian's Wall.

In the later 2nd early 3rd century AD the curtain wall was replaced with a new one twenty-two feet high incorporating the typical semi-circular towers projecting from it and with a recut defensive ditch.

Evidence of the semicircular towers can still be seen along sections of the wall as seen below.

Perhaps some of the best sections of the original Roman wall are to be found along the north wall were large sections still stand almost to the level of the walkway as you follow the route of the Shropshire Union Canal.

Working our way along the northern ramparts we reached the end of what remains of Roman Chester's wall at the modern 1966 St Martin's Gate that bridges the road and allows a view of the pavement below where the position of the north west angle tower is marked out at the foot of the steps to the bridge.

|

| The Roman north-west angle tower marked out on the pavement below |

|

| The new houses along this side of St Martin's Way follow the route of the demolished Roman western wall |

Referring back to the model of the Roman city of Chester illustrates just how close the original course of the River Dee came to the now demolished western wall.

|

| The top of this picture of the model of Roman Deva shows the original course of the River Dee through ground now occupied by Chester Race Course |

Chester worked hard over the centuries to maintain its access to the sea and the trade that access brought it, but time and silting gradually caused the river to become unnavigable to larger ships and indeed the silted land became the prime spot for the development of Britain's first race course which came to occupy the site of Deva and Chester's harbour.

This is a busy time of year for Chester Race Course and looking at this area it is hard to imagine how the Roman harbour would have looked, so without any period pictures to call on I grabbed a picture from my trip to London last week and the model of the Roman harbour in Londinium to aid the imagination.

If you take the time to look, the original Roman harbour wall is still visible at the back of the car-park underneath the foot of the medieval wall that extended down to the waterfront.

|

| The original Roman harbour wall of Deva now firmly upon dry land |

As mentioned, repair of the Roman wall was an ongoing process and the Romans reused gravestones and monuments from a disused part of their cemetery outside the Northgate of the fortress.

These tombstones laid sealed away and protected from the elements for sixteen hundred years until revealed and recovered in the late 19th century during repair work to the wall.

This amazing collection, perhaps some of the finest Roman gravestones now form part of the Roman exhibition in the Grosvenor Museum.

In the second part of this post on Roman Deva Victrix we will look at the collection of items discovered in the city from this period on display in the Grosvenor Museum.

Awesome post as usual!

ReplyDeleteThank you. I enjoy putting these posts together as I find the process reinforces my own understanding, so it is really great when others enjoy reading it as well.

DeleteThanks again

JJ

What a fantastic post! Thanks so much for sharing it.

ReplyDeleteHi,

DeleteMy pleasure and thank you for taking the time to comment, not only that but also being the one thousandth comment on the blog.

JJ

Wow, that was a great read. I love that history you can touch. I'm envious because our history here in the States only really starts in the colonial period in regards to sites you can still visually see. Thanks for posting!

ReplyDeleteHi Adam,

DeleteThank you, very pleased you enjoyed the read. Wait till you see what the Grosvenor Museum holds!

I am very conscious of my reading population from across the pond and the fact that I am able to depict history from nearly two thousand years ago.

We are very fortunate in Britain in that we have a lot of history, packed into a relatively small island, stretching back several thousand years, informed by a very good body of archaeological research to help unravel and understand it.

It is easy for us, living here, to be a bit blaze about it but I never grow tired of simply being amazed about what is on our very doorsteps, I live near Exeter, one of the first major Roman settlements, I also spent much of my professional life driving over large parts of the country using roads built by the Romans, and I am very keen to share that with others who don't have a similar experience or are as amazed as I am.

I find this stuff inspires my wargaming as I hope it does for others.

Thanks again

JJ