Corunna Retreat - Peninsular War Tour 2019

Battles and Actions in the Tagus Valley(Alcantara and Almaraz Bridges) - Peninsular War Tour 2019

Battles and Actions in the Tagus Valley, Battle of Talavera - Peninsular War Tour 2019

Badajoz, The French Siege and Allied First, Second and Third Sieges - Peninsular War Tour 2019

Cavalry Actions in Estremadura - Peninsular War Tour 2019

|

| Map of Estremadura from Oman's History showing the location of Elvas and Albuera |

I have covered the role of the fortress town of Elvas, in my previous post looking at the sieges of Badajoz, similar to its sister Portuguese town Almeida in the north of the country, acting very much as the Allied garrison and command centre for the Anglo-Portuguese forces operating on that part of the frontier.

The star shaped defences of this important frontier town has earned it UNESCO World Heritage Status and that, as much as any other reason, would recommend it to the Peninsular War traveler, as well as its important role during the conflict.

The majority of the fortifications date back to the 17th century and the War of Restoration as Portugal fought Spain to establish its independence and, like other fortresses in the area, it bears the common features of a typical Vauban defence, which saw the town resist four Spanish attempts to take it in 1644, 1659, 1711 and in 1801 during the War of Oranges.

It was the Romans that first identified the importance of the site Elvas now occupies, but like so many major centres in the region, it was the Moors that have left their mark on the architecture, ruling here for five-hundred years.

|

| On the road into Elvas the walls and Romano-Moorish castle, top left, dominate the heights above |

The entrance to the town is dominated by the massive 16th century Amoreira Aqueduct, stretching over four and half miles and towering up to one-hundred feet above the road below; the aqueduct was built to carry water from the spring of Amoreira some five miles away, this after the single well in the town began to fail in the late 15th century.

Built with 843 arches, the aqueduct took one-hundred years to complete, feeding water into an underground cistern, now only used to feed water into the town fountain.

|

| The 16th century Amoreira Aqueduct seen on the road into Elvas |

I have to say both Carolyn and I loved Elvas which is a beautiful town incorporating its buildings around little squares and cobbled streets, with some glorious restaurants to be sought out by the tired and hungry Peninsular War tourist.

Talking of the Peninsular War, Elvas is also home to one of the oldest British military cemeteries in the world.

Formerly known to the Portuguese as the 'English Cemetery' on a common assumption around the world that all who hail from the British Isles are English, which they are most definitely not, the cemetery was practically lost from memory until rediscovered about twenty years ago and fully refurbished into the beautiful memorial garden the visitor can see today.

|

| The road leading up to the entrance to the British Cemetery with the Chapel of St John of Corujerra to its left |

The cemetery occupies the half-bulwark of Sao Joao da Corujerra, named after the 13th century Chapel of St. John of Corujeira built by the Knights Hospitallers in 1228 now also fully restored and that lies next to the entrance.

The cemetery was established by the British during the Peninsular War and the first person to be buried there was Major General Daniel Houghton, commander of 3rd Brigade (29th, 1/48th, 1/57th Foot), 2nd Division, killed during the battle of Albuera on 16th May 1811.

As the work began to clear the cemetery of years of neglect, other graves were uncovered, that of Lieutenant Colonel James Ward Oliver, 4th 'King's Own' Foot, who commanded the 14th Portuguese Line and who died at Elvas on 17th June 1811 from wounds received at the siege of Badajoz, Lieutenant Colonel Daniel White, 29th Foot, part of Hoghton's brigade and also killed leading his battalion at Albuera, Major William Nicholas Bull who died on 14th February 1850 and Mrs Caroline Bull, his wife, who died in 1863 and was buried beside her husband.

|

| The British Cemetery and nearby chapel are perched on a bastion overlooking the border countryside |

In 1996 the Association of Friends of the British Cemetery (FBC) was formed and following work to clear the area of rubble, prune bushes and whitewash the walls, on November 11th that year the first service of remembrance was held, followed a year later by a service for Albuera Day in remembrance of those who fell at the Battle of Albuera, both ceremonies now an annual event since then.

|

| It was really great to see the work carried out by Peninsular War 200 to remember the two hundredth anniversary of the war with a re-memorialising of key sites we visited on our tour. |

|

| The view from the bastion towards the Spanish border captured in the tile art below showing the position in relation to Badajoz and Albuera |

The British Cemetery is a credit to the work of the FBC, headed up, as President, by Lady Jane Wellesley, daughter of the 8th Duke of Wellington, which is a registered UK charity, with Gift Aid Scheme status and administered by a trust.

|

| Given that most soldiers who fell in this era have no known grave, this small cemetery is moving memorial to their sacrifice and suffering. |

|

| 'Sacred to the memory of Lieutenant Colonel James W. Oliver who was mortally wounded at the Badajos and died in this city the 17th June 1811' |

In my travels, I have visited many British-Commonwealth War Cemeteries around the world, from Northwest Europe, the Mediterranean and the Far East, run and administered by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, with some that stick out in the mind for their beautifully tranquil locations, but I have to say that Elvas ranks right up there with the best and I would recommend visitors to take the time to visit if the opportunity presents.

|

| Forte de Graca |

I think I mentioned in my preamble about the delights of Elvas and its restaurants, and I thought I would mention one in particular that found Carolyn and I standing in a queue with other residents of the town in a certain Piri-Pri Chicken Bar.

I mentioned the delights of this classic Portuguese dish whilst visiting Almeida and the River Coa and so with this, our last stay in Portugal on this tour, we decided to go where the locals went for their evening's tea and boy were we treated.

Perhaps the locals were a bit surprised to find English tourists joining them in the queue but our hosts were most inviting and very patient with my mix of broken Portuguese and English and rustled up the most tasty take away chicken with extra piri-piri you could die for.

I don't know why we can't get food like this in the UK, so if some entrepreneurial Portuguese caterers are reading this, get over here and get cooking because the market is wide open to this real taste of Portugal.

|

| Living the dream! |

Both Carolyn and I really enjoyed our stay at Elvas and the town proved an excellent base to locate ourselves at for our travels in the area.

Thus we come to the final location that I was really looking forward to visiting whilst in Estremadura and that was the battlefield of Albuera, a battle I have studied ever since reading about it in my library copies of Sir Charles Oman's History back in my mid teens.

Since those days I have come to appreciate the peculiarities of this battle that make it stand out from others fought in the Peninsular War and is one that really illustrates why commanders tried to avoid the situation that occurred in this particular battle, namely a lengthy exchange of musketry between opposing lines of infantry, not to mention the drama of cavalry charges over a rain affected battlefield that saw the French snatch defeat from the jaws of victory because as Marshal Soult declared the enemy just didn't know when they were beat.

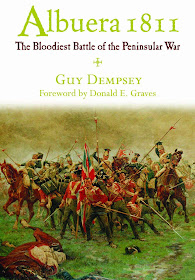

As in previous battle site walks I have recommended a book that I referred to in the planning and visit to the site discussed and in this case I would not hesitate to recommend 'Albuera 1811, The Bloodiest Battle of the Peninsular War' by Guy Dempsey which is another classic example of a book that forensically explores the battlefield in a focused look at what happened, where, to who, and specifically at a given time with all the usual caveats that apply 'to the best of anyone's knowledge' based on the evidence of those who witnessed what happened.

The maps are excellent and are based on the Spanish topographical walking maps that I was carrying alongside the electronic navigation tools, and thus allow the visitor to start to imagine the ground occupied by the various units in the actions described - highly recommended.

|

| One of my favourite books in my library and a classic reference for the Battle of Albuera |

Another way to imagine the ground is to see it modelled in a way that captures the drama of the events that occurred there in 1811 and so I have chosen to intermix my pictures of the battlefield with the models of Curro Agudo Mangas that can be seen in the Luis de Morales Museum in Badajoz, that I hope will really add to the accounts from the veterans that took part.

The two key battles of the Peninsular War that occurred in 1811 were perhaps the Battle of Fuentes de Onoro on the 1st to 3rd of May and the Battle of Albuera on the 16th May, that saw both French armies in the north and south driven back by combined Allied armies.

I find it interesting to consider that both battles share some similarities in the approach taken by both French commanders, Marshals Massena and Soult, both off the back of experiencing trying to tackle Allied and particularly British infantry in positions, head on and suffering the consequences.

In these two battles we see both commanders look to pin the Allied line around a built up area and use the French advantages in speed of manoeuvre to take advantage of a covered approach and rapidly turn the Allied line to present opportunities for the French combined arms attacks of infantry columns covered by mass skirmishers and supported by cavalry and artillery to support them.

It is probably in these two battles that the French in Spain came the closest to defeating an Allied army with British troops involved, and both Wellington and Beresford were tested to the extreme in their abilities to respond quickly and reposition their respective lines to deal with the French manoeuvre; and therein lies another interesting compare and contrast situation with how the two commanders responded and the rapidity of that response.

Wellington didn't claim Fuentes as a victory, but the losses suffered at Albuera by his subordinate forced him to do so to offset the likely disquiet at home once the awareness of the losses suffered became more widely appreciated.

|

| La Albuera remembers the sacrifice of those who gave their lives for Spanish independence |

As covered in my post looking at the sieges of Badajoz, the battle of Albuera was brought about by Marshal Soult marching up from his positions in the south of Estremadura to break the siege of Badajoz by the Allied army led by General Beresford after he had invested the city on the 5th of May and commenced siege operations with the first trenches dug on the 8th, seeing the Allies suspend their work on the 14th when news reached them of Soult's approach, following reports from Seville that he had left the city with his troops in the middle of the night 9th/10th May.

Wellington was very clear on how he wanted the campaign against Badajoz conducted while he was away in the north dealing with the French Army of Portugal, recently driven back over the border to Ciudad Rodrigo, and he outlined his plans to Beresford in three memoranda, all dated 23rd April 1811 in which, importantly, he gave him discretion on how to respond to a French advance.

In it he stated;

'All this must be left to the discretion of Sir William Beresford. I authorise him to fight the action if he should think it proper, or to retire if he should not.'

However if Beresford decided to fight, Wellington was in no doubt as to where he should offer battle, stating;

'I believe that, upon the whole, the most central and advantageous place (for Beresford) to collect his troops will be at Albuera.'

Unfortunately Wellington did not go on to give his specific reasons for that choice, but the position of Albuera in front of a river crossing, on the main road up from Seville, together with other roads allowing access to Spanish armies operating in the area to get there speedily and a route back to Elvas should a retreat be required, all seem likely reasons for the choice.

La Albuera lies about sixteen miles southeast of Badajoz on the Royal Road leading from Badajoz to Seville and is described as being in 1811 a town of about 150 'very indifferent' houses.

Lieutenant Moyle Sherer of the 1/34th Foot described it when he and his battalion arrived at five in the evening on the 15th May after marching from Valverde at midday;

'It is a small inconsiderable village, uninhabited and in ruins: it is situated on a stream from which it takes its name, and over which there are two bridges; one about two hundred yards to the right of the village, large, handsome, and built of hewn stone; the other, close to the left of it, small, narrow, and incommodious. This brook is not above knee-deep: its banks, to the left of the small bridge, are abrupt and uneven; and, on that side, both artillery and cavalry Would find it difficult to pass, if not impossible; but to the right of the main bridge, it is accessible to any description of force.

The opposing armies stood too before dawn on the 16th May, but it soon became obvious that neither army was prepared to make any obvious move, as the Allies were content to hold their position and the French were still arriving off the Seville road.

|

| The smaller of the two bridges defended by the 1st KGL Light Infantry. Note the rising ground up to the village, mentioned by Sherer in his description of the area. |

Sherer described the initial Allied deployment as shown in Oman's map above;

'On the morning of the 16th our people were disposed as follows:

The Spanish army, under the orders of General Blake, was on the right, in two lines; its left rested on the Valverde road, on which, just at the ridge of an ascent, rising from the main bridge, the right of our division (the second) was posted, the left of it extending to the Badajos road, on ground elevated above the village, which was occupied by two battalions of German riflemen; General Hamilton's Portuguese division being on the left of the whole. General Cole, with two brigades of the fourth division (the fusileer brigade and one of Portuguese), arrived a very short time before the action, and formed, with them, our second line.

These dispositions the enemy soon compelled us to alter.'

By 08.00 Soult had obviously seen enough of the Allied dispositions to decide him on his plan of attack, particularly as with the bulk of his enemy in view on the heights above the town, he could discern the yellow and other assorted colours of the Spanish troops on the Allied right alongside the redcoats and Portuguese in blue.

Lieutenant Charles Leslie of the 29th Foot described the scene;

'We had scarcely time to get a little tea and a morsel of biscuit, when the alarm was given—"Stand to your arms! The French are advancing."

We accordingly instantly got under arms, leaving tents and baggage to be disposed of as the quartermaster and bat-men best could. We moved forward in line to crown the heights in front, which were intended for our position, and which may be shortly described as follows. The rivulet of Albuera ran nearly parallel to the front of the heights, at about six hundred yards' distance, which sloped down to it, these being perfectly open for all arms; but beyond our right they swelled into steeper and more detached ones.

The village of Albuera was nearly opposite the centre of our line, and on the same side of the water; at which point was the only bridge. The banks of the rivulet were at some places steep and abrupt. On the opposite, or French side, they were rather low, and the ground flat and open for some little distance; then gradually rose to a gentle height, covered with wood, particularly at some distance from the bridge up the river, where the French army lay concealed from our view, they having only some detached parties of cavalry in the open ground.

|

| A very dry River Albuera with the smaller of the two bridges to the right and the outskirts of the modern town on the heights above |

In occupying the position the army was formed as follows: —The Portuguese, in blue, on the left; the English, in red in the centre—viz., General Houghton's brigade, the 29th, 57th, and 1st battalion of the 48th Regiment; General Lumley's, 28th, 39th, and 34th Regiments; Colonel Colbourn's, the 3rd, the 2nd battalion of the 48th, the 66th, and 31st Regiments; and the Spaniards, in yellow or other bright colours, formed the right.

The whole were drawn up as for a grand parade, in full view of the enemy, so that Soult could see almost every man, and he was also enabled to choose his point of attack; which would not have been the case if we had been kept under cover a few yards farther back, behind the crest of the heights, or had been made to lie down, as we used to do under the Duke of Wellington. That part of the 4th Division under Sir Lowry Cole, which had just arrived from Badajos, were posted in second line in our rear.

The enemy occupied a very large extensive wood, about three quarters of a mile distant, on the other side of the stream, and posted their picquets close to us. The space between the wood and the brook was a level plain; but on our side the ground rose considerably, though there was nothing which could be called a height, as from Albuera to Valverde every inch of ground is favourable to the operations of cavalry not a tree, not a ravine, to interrupt their movements.'

|

| The dry river bed here at the old bridge shows how relatively shallow it was, thus allowing the French to ford it in places as well as using the bridges during their attack on the town. |

Before we had time to halt in our position, we observed two large columns of the enemy, supported by cavalry and artillery, moving towards the bridge and village of Albuera, which was occupied by the light corps of the German Legion under Colonel Hacket. The first attack here commenced, under cover of a heavy cannonade, upon the village and our line in its rear.

The Germans made a gallant defence, and maintained their post; but as the enemy apparently seemed to make a push at this point, Colbourn's brigade was ordered to move down in support of the troops in the village.'

|

| Godinot's brigade presses forward in column onto the new bridge, under fire from the KGL skirmishers |

Soult had launched General de Division Godinot and his Second Independent Brigade, some eight battalions including a combined battalion of grenadiers, at the new bridge in front of the town, supported by Briche's light cavalry, the 27th and 21st Chasseur a Cheval together with the 4th Dragoons and the Vistula Lancer supported by a horse battery.

|

| Marshal Soult, pictured here in his younger days, as he would have looked whilst commanding at Albuera |

The attack was a feint designed to draw more Allied troops into defending the town whilst the main attack would develop on the Allied right.

Needless to say the French commander must have been delighted to see the Colborne's brigade of redcoats move down off the heights towards the battle now underway around the bridges.

Major General Charles Alten commanding the First Independent Brigade, Kings German Legion, described the attack on his soldiers defending the new bridge;

'(A) close column (of French) ... advanced up to the bridge but owing to the well directed fire of the 2nd Light Battalion and of its advanced marksmen, the latter repeatedly picking off the officers who led the enemy column, the enemy failed several times in forcing this passage. After different fruitless attempts and a heavy loss, the column however succeeded in crossing the Albuera, partly by the bridge and partly by fording.'

|

| The lead troops of Godinot's column move onto the new bridge, with skirmishers fording the river either side |

|

| General de Division Nicolas Godinot led his brigade in the attack against the town of Albuera |

By 09.00, with the attack on Albuera well underway, the Allies got their first indication of the threat developing on their right as the cavalry that crossed the Albuera with Godinot's infantry suddenly swung left and rode across the front of the Allied lines; this move soon followed by disturbing news that other elements of Soult's army had been observed crossing the Nogales and Chicapierna streams causing Beresford to ride over and join Spanish General Blake to observe the situation for himself.

|

| Teniente General Don Joaquin Blake commanding 4th Adalucian Expeditionary Corps |

With the threat to the Allied right confirmed, Beresford ordered Blake to reposition his troops to face the developing French attack.

|

| Colours of the 57th 'Die Hards' ,so named after their heroic stand at Albuera and the 77th East Middlesex Foot buried in front of the memorial |

|

| The larger or 'new' bridge as depicted in the model below |

This first stage of the battle saw Alten's KGL brigade of 1,100 men up against Godinot's brigade of 4,000.

Behind them Beresford would have observed from the high ground General de Brigade Francois Werle's 6000 men of the First Independent Brigade and perhaps 2,000 dragoons in the two cavalry brigades; and suspecting Soult to have the rest of his army along the Seville road out of sight, he can perhaps have been forgiven for committing Colborne's brigade to support Alten in the town and then being at first unsure about reports of Soult's change of direction, knowing the French commander could easily commit his troops either way.

This doubt about the French direction of attack even caused General Blake to question his repositioning of the Spanish line to the Allied right flank until further observations confirmed the validity of the initial reports.

|

| The view from the new bridge on the Allied side of the river looking towards Albuera |

|

| The view across the new bridge looking towards the French side of the river |

|

| KGL Light Infantry in battle around the church in Albuera against French troops that have managed to force a way forward from the bridges below the town |

|

| The church is, as most churches are at battle sites in the Peninsula, a veteran of the battle fought around it and makes an easy landmark from which to get ones bearings |

However, alongside the events on the Allied right flank, a bitter battle would continue along the river and in the town, as Godinot's troops pushed Alten's men back into it.

|

| Godinot's brigade included a battalion of combined grenadiers |

|

| The church bears its battle scars on its walls |

|

| Just as at Salamanca there is a Battle Information Centre next to the church, and just as at Salamanca it was closed! |

|

| French skirmishers press on into Albuera |

|

| An abiding memory of our holiday in Spain 2019 |

The repositioning of the Spanish line perhaps took half an hour for the respective battalions to face right and create a new line extending down to the Chicaperna stream with a second line positioned directly behind.

However by 11.00 the French troops were up on the higher ground to the right of the town and advancing towards the Spanish line with nineteen battalions of veteran French infantry, supported by strong elements of both cavalry and artillery, knowing full well how many times Spanish infantry had been routed on open ground in similar circumstances with the Battle of Gevora outside of Badajoz fresh in the memory.

The French advance had been accompanied by a dramatic change in the weather as described by French surgeon Jean-Baptiste d'Heralde;

'At this moment, a rain mixed with hail struck our faces and added to the difficulties of our infantrymen who, already wet to the knee from their stream crossings, struggled to reach the crest of the ridge.'

|

| General de Division Jean-Baptiste Girard Commanded V Corps at Albuera |

The decisive moment in the Battle of Albuera had been reached as General de Division Jean-Baptiste Girard at the head of V Corps advancing along the ridge came into view of the Spanish line with as General de Brigade Jean Maransin describing the advance of V Corps;

'Having arrived at the point of attack (on the crest of the ridge), the V Corps changed direction by a movement of the head of the column to the right; Girard's division marched towards the enemy in attack columns, the second division was 150 paces behind in attack columns by battalion.'

As Dempsey points out in his book, there has been much debate on the formation of attack used by Girard's troops, because of other sources describing other types of manoeuvre columns; however quoting from Napoleon's guidance notes to his commanders on the appropriate column to adopt, after French battalions changed from a nine to a six company structure, it is clear that battalions in attack columns were two companies wide if both elite companies were attached and one company wide if not.

Given that the French were attacking with combined grenadier battalions and likely having voltigeurs detached to skirmish ahead it is most likely that the French approached in columns one company wide as seen in the model as the French approach the Spanish line.

|

| The Information Board close by informs visitors of the events that happened in the fields beyond |

One question that Dempsey discusses in the book is Girard's decision to press his attack in column once he observed the Spanish line drawn up ahead to meet him and it seems likely that seeing the mass of Allied troops moving behind the Spanish and interpreting that as their attempt to disengage he felt that the impetus of the attack would be better prosecuted in column, relying on the performance of previous Spanish infantry lines to break before the French columns allowing the French cavalry to get in among them and their supports.

However as events showed, that plan fell apart on first contact with the enemy and the officer casualties suffered by the French as the Spanish line held firm only added to their woes.

Surgeon Jean-Baptiste d'Heralde;

'The Spanish artillery ... pounded the ranks of the 1st Division, which found itself in critical danger. General Bayer had his left leg broken by a gun shot. His aide-de-camp Carlier was killed. General Girard's horse was killed and he himself was wounded. His first aide-de-camp (Duroc) Mesclops was mortally wounded, as was his engineer officer, Captain Andouan (Andoucaud). Chief of Staff Hudry had his horse killed. The two commandants (majors) of the 40th Line, Bonneau (Gaspard-Bonnot) and Supersaque (Supersac), Grenadier Captains Lamare (Delamarre) of the 40th Line, (and) Combarieux (Combarlieu) of the the 34th ... were already killed or mortally wounded'

|

| The French arrived in a column of companies before the Spanish line. only to find their enemy resolute and delivering well aimed musketry and roundshot |

The French desperately tried to shake out into line or to bring other columns forward to simply add more muskets into their part of a developing firefight with the Spanish, and in the process General de Division Honore Gazan leading 2nd Division fell wounded trying to bring some order to the situation.

|

| General de Division Honore Gazan commanded 2nd Division of V Corps |

Captaine Edouarde Lapene of the French artillery described the scene of growing disorder among the French ranks;

'Not a shot missed our column, still formed in serried masses, and we were only able to reply with insufficient musketry of our first two ranks.

Our soldiers were falling left and right without being able to defend themselves and the survivors fell prey to the darkest discouragement.'

The French needed desperately to form into line to be able to compete with the Spanish musketry, but were now stuck, falling rapidly into disorder and, to make matters worse, with a newly arrived brigade of British infantry arriving on their left flank.

Major General William Stewart had been marching his British 2nd Division 'at the double', as Lieutenant John Clarke of the 66th Foot recalled to bring his soldiers into a new position to support the Spanish holding the Allied right flank.

This had taken longer than preferred due to Stewart's preference to lead with Colborn'e brigade which had to be extricated from its support of Alten's KGL in Albuera before the move could be initiated.

|

| The view looking down the Spanish line to the left of picture towards the flatter ground near the Chicapierna stream |

Once completed Stewart had all three brigades on the march in open company columns, similar to the French formation but with longer intervals between the companies.

Taking advantage of a track on the reverse slope, the long column hove into view of the French artillery supporting their stalled attack and now redirected some well aimed fire against the British arrivals as mentioned by Ensign Benjamin Hobhouse of the 57th Foot;

'During our advance in column the incessant and well-directed fire of the French artillery mowed down many of our poor fellows.'

Lieutenant Sherer of the 34th Foot also recalled the results of this fire against the two brigades that preceded his;

'We formed in open column of companies at half-distance, and moved in rapid double quick to the scene of action. I remember well, as we moved down in column, shot and shell flew over and through it in quick succession: we sustained little injury from either; but a captain of the twenty-ninth* had been dreadfully lacerated by a ball, and lay directly in our path.

We passed close to him, and he knew us all; and the heart-rending tone in which he called to us for water, or to kill him, I shall never forget. He lay alone, and we were in motion, and could give him no succour; for on this trying day, such of the wounded as could not walk, lay unattended where they fell: all was hurry and struggle; every arm was wanted in the field.

*Identified by Dempsey as Captain John Humphrey.

Stewart's lead brigade arrived at the extreme right of Allied line at 11.00 just as the French were driving in the Spanish skirmish line, and realising the advantageous position it offered him to get onto the flank of the French columns, he directed Colborne's brigade to carry on marching past the right flank of the Spanish line, preparatory to turning into line to deliver a telling fire that would exploit their advantage.

However the move would expose Colborne's brigade's flank, and given the amount of French cavalry in the area it would have been prudent to have had the last unit in column or square to protect the line, but one source suggests Colborne's proposal to do so was overruled by Stewart; however Colborne certainly never made any public statement to confirm this account although he seems to have suggested it in private communications on the matter.

Dempsey quotes a description about the affair given by Sir James Wilson, commanding the 1/48th Foot in Stewart's second brigade;

'The confusion and rout of the 1st Brigade appears to have originated in some little misunderstanding between Lt. Col. Colborne of the 66th Regt. who commanded it and General Steuart. The latter being in charge of the Division would not have been supposed to interfere in the immediate formation of his brigade. He however directed it himself, ... contrary to the wishes and suggestion of Col Colborne, who is a most excellent officer.'

On the face of the description of the advance of Colborne's columns it would have seem to have been a simple exercise for each battalion to have its companies make a quarter wheel left to bring them into line facing the French flank, but it appears Stewart complicated matters still further by ordering the battalions to form on the right of their grenadier companies in complete reversal to normal practice.

This, added to the lead battalions not advancing far enough before turning to face the French flank and thus not allowing enough room for the rearward battalions to join the line, caused yet more delay in a smoke and rain obscured battlefield and allowed the French infantry to prepare a line of columns facing the British when they eventually moved forward to engage.

Major William Brooke, 2/48th described the scene;

'On gaining the summit of the hill we discovered several very heavy columns of French troops ready to receive us. The British line deployed, halted, and fired two rounds; the heads of the French columns returned the fire three deep, the front rank kneeling.'

It seems the firing between the two opposing lines was close and fierce and struck several observers with its intensity;

Lieutenant Robert Brown Dobbin of the 66th Foot recorded;

'...the French fight so well as they did on this occasion. We were often firing at not more than ten yards distance before we came to the charge, and that for two or three minutes together.'

He continued;

'A Frenchman made a snap at me when I was in Front, and not five yards distance, but his piece missed fire, and he was taken down in a moment by a man of my company named Boland.'

Lieutenant Charles Madden of the 4th Dragoons observing the firefight;

'The French being strongly supported stood firm, and a more awful scene was never witnessed; it was perfect carnage on both sides, bayonet against bayonet for nearly half an hour.'

Seeing the French resolution in the face of the British firing, Stewart opted to lead with the bayonet by initiating a charge and even here Albuera stands out in the annals of Napoleonic battles seeing the rarity of bayonet to bayonet combat.

Lieutenant Edward Close 2/48th Foot described this stage in the fighting;

'Two or three shots were fired by our regiment, when, irregularly formed as we were, we charged. The left column of the French became opposed to the left wing of the Buffs and our right. Their centre column faced our two left companies and the 66th Grenadiers. Their right column, which had escaped our notice, found its way to our rear.

The French left column was broken, and was the only part of their troops which stood the charge. They remained as if powerless until they were bayoneted by our men.

The rear companies fled. The centre column ... however gave way as soon as we charged.'

Lieutenant Robert Brown Dobbin of the 66th Foot in a letter to his father described the fierce French resistance;

' ... when we did charge, the french never moved until we came Bayonet to Bayonet, and as soon as we dispersed one column another appeared which we served as the former.'

In spite of their success the men of Colborne's brigade were finding conclusive success elusive as the French columns that had fled, rallied on their support and recommenced firing, whilst other columns not dealt with, such as that mentioned by Lieutenant Close of the 2/48th, started to get into the rear of the British line and threaten its momentum.

Despite this the British commanders opted to charge yet again, seemingly to ignore the growing disorder the casualties were causing among their own ranks as described by Lieutenant Crompton of the 66th Foot

'We fought them until we were hardly a Regiment. The Commanding Officer (Captain Benning) was shot dead, and the two officers carrying the Colours close by my side received their mortal wounds. In this shattered state our Brigade moved forward to the charge. Madness alone would dictate such a thing.'

With the French surprise flank attack stalled before a resolute Spanish line and now finding itself outflanked and outnumbered by an Allied army turning to face the perceived threat, Marshal Soult would have been forgiven if he had decided to withdraw to live to fight another day; but the Battle of Albuera had yet another twist in stall, as the French cavalry entered stage left to completely alter the situation and all but destroy a four battalion British infantry brigade and almost its Army commander at the same time.

However the movement forward by the French horsemen was enough to cause the Buffs to at least throw back their right wing to try and protect the rest of the brigade as depicted in the model below

Even as the enemy lancers approached the refused flank of the Buffs, yet more confusion ensued as a cry went up that the lancers were Spanish and for the men to hold their fire.

The Buffs were subject to the full force of the enemy charge and were annihilated by it, being cut down almost to a man and shown no quarter.

The battalion started the day with 27 officers and 728 other ranks and by the end of it could only muster 85 unwounded men including seven officers, with 112 survivors in total and a loss of 85%.

One anonymous private of the Buffs recalled what happened to him and many of his comrades;

'I was knocked down by a horseman with his lance, which luckily did me no serious injury. In getting up I received a lance in the hip, and shortly after another in my knee, which slightly grazed me.

I then rose, when a (French) soldier hurried me to the rear a few yards, striking me on the head with his lance. He left, and soon another came up, who would have killed me had not a French officer came up, and giving the fellow a blow told the fellow to spare the English (prisoners), and to go on and do his duty against ... (the rest) of my unfortunate comrades.

The officer directed me to the rear of the French lines and here, the sight that met the eye was dreadful! Men dead, where the column had stood, heaped up on each other; the wounded crying out for assistance and human blood flowing down the hill!

I came to where the baggage was where I found a vast number of my own regiment, with a good proportion of officers prisoners, like myself; numbers of them desperately wounded even after they were prisoners!

Here then I offered up my most fervent thanks to Heaven for having escaped so (relatively) safe.'

The Colours or standards of a particular regiment were always highly prized by their owners as symbols of that units prestige within the wider army and were thus highly prized by the enemy as symbols of their own prowess in having captured them, knowing the intensity of fighting that would entail to do so.

|

| King's Colour, '3rd 'Buffs' Foot |

British battalions carried two such Colours, the Kings which in line regiments was the Union banner usually with a shield device at its centre with the number of the regiment displayed surrounded by a wreath of flowers representing each country in the Union.

|

| Regimental Colour, '3rd 'Buffs' Foot |

In addition, the Regimental Colour would be born alongside it usually in the facing colour of the regiment as displayed on their collars and cuffs with a small Union banner in its top corner nearest the staff and with a similar shield and Union wreath as on the King's colour.

|

| The Latham Centrepiece c1880, 3rd East Kent Regiment of Foot, Lieutenant Matthew Latham saving the King's Colour at the Battle of Albuera 16th May 1811 as pictured in the National Army Museum in April this year. https://jjwargames.blogspot.com/2019/04/treasures-in-national-army-museum.html |

The first bearer of the Buffs King's Colour at Albuera was fifteen year old Adam Walsh who struggled to defend his charge against the attack from the lancers and was joined by Lieutenant Mathew Latham who took the Colour from Walsh with terrible personal consequences for himself.

Doctor John Morrison who joined the 3rd Buffs and later cared for Latham, described what happened;

'He was attacked by several French Hussars, one of whom seizing the flag-staff, and rising in his stirrup, aimed a stroke at the head of the gallant Latham, which failed in cutting him down, but which sadly mutilated him, severing one side of the face and nose; he still however struggled with the dragoon, and exclaimed, "I will surrender it only with my life".

|

| Lieutenant Mathew Latham - engraving from J. Carpue - An Account of Two Successful Operations (London 1816) |

A second sabre struck severing his left arm and hand, in which he held the staff, from his body. The brave fellow, however, then seized the staff with his right hand, throwing away his sword, and continued to struggle with his opponents, now increased in number, when ultimately thrown down, trampled upon and pierced by the spears of the Polish Lancers, his last effort was to tear the flag from the staff, as he thus lay prostrate, and to thrust it partly in the breast of his jacket.'

The young Ensign Walsh was wounded and taken prisoner, but later managed to escape and rejoin the battalion.

The next battalion in the brigade to be struck was the 2/48th, suffering a similar fate with little organised resistance established once the cavalry were in amongst their line.

Lieutenant Edward Close wrote;

' ... their cavalry ... rode through us in every direction, cutting down the few that remained on their legs. There was nothing left for it but to run.

In my flight I was knocked down by some fugitive like myself, who I suppose, was struck by shot.'

The battalion was not as badly cut up as the Buffs but suffered terribly, starting the day with 519 all ranks and ending it with 355 a loss of 32%.

One officer in the battalion complained of the barbarous behaviour of the Lancers, suggesting in his opinion that many of them were 'intoxicated' and how in the heat of the battle they rode over the wounded darting their lances into them as they passed.

The next battalion to be engulfed in French cavalry was the 2/66th 'Berkshire' Regiment of Foot, seriously weakened earlier after its firefight with the French infantry.

Nineteen-year-old Lieutenant John Clarke described the attack on his battalion;

' ... at this moment a crowd of Polish Lancers and Chasseurs-a-Cheval swept along the rear of the Brigade; our men now ran into groups of six or eight, to do as best as they could; the officers snatched up muskets and joined them, determined to sell their lives dearly.

Quarter was not asked, and rarely given. poor Colonel Waller, of the Quarter-Master-General's staff, was cut down close to me; he put up his hands asking for quarter, but the ruffian cut his fingers off.

My Ensign (James) Hay, was run through the lungs by a lance which came out of his back; he fell, but got up again. The Lancer delivered another thrust, the lance striking Hay's breast-bone; down he went, and the Pole rolled over in the mud beside him ... The Lancers had been promised a doubloon each, if they could break the British line.

In the melee, when mixed up with the Lancers, Chasseurs-a-Cheval and French infantry, I came into collision with a Lancer, and being knocked over was taken prisoner; an officer ordered me to be conducted to the rear.'

The success of the French cavalry charge had not gone unnoticed by General Lumley commanding the Allied horse on the ridge further along, but conscious of his being severely outnumbered, but still needing to try and intervene he dispatched four squadrons, two of which were Spanish, whilst the others were from the the 4th Dragoons.

The two Spanish squadrons advanced as ordered but then pulled up short before engaging, the 4th Dragoons, however, charged home. This was their first encounter with enemy lancers.

Lieutenant Charles Madden left an account of the charge;

'The charge of our right wing was made against a brigade of Polish cavalry, very large men, well-mounted; the front rank (was) armed with long spears, with flags on them, which they flourish about, so as to frighten our horses, and thence either pulled our men off their horse or ran them through. They were perfect barbarians, and gave no quarter when they could possibly avoid (it).

We had ... two captains, and one lieutenant taken, and one captain and one lieutenant severely wounded, with a great proportion of men and horses killed and wounded.'

The most significant effect of the Allied cavalry charge was to cause enough of a distraction to allow a significant number of British soldiers to escape back to their own lines, including Colonel Colborne.

|

| Marshal Beresford deals with a Polish Lancer who rashly attempted to take on the Allied Commander after having broken through into the centre of the Allied line. |

The French cavalry charge had reached its zenith and by now order had been lost with just small groups of cavalrymen operating together which did much to allow the last battalion in Colborne's brigade which due to the rather confused deployment into line by the brigade had not allowed room for the 2/31st Foot to deploy from its column as it crested the ridge line.

As the enemy cavalry came forward from among the wrecks of the other three battalions Major L'Estrange commanding, was able to get the 31st into an impromptu square of his own devising as recorded by Major General Stewart's report, although his account disputed the fact that they were attacked by the cavalry, which other eyewitness accounts clearly disprove;

'The 31st Regiment, the left of the brigade, not having been attacked by the cavalry, retained, by its steadiness and spirit, the summit of the hill which had been gained by the rest of the brigade.

The conduct of this small corps (320 men in action at the start of the battle) under the command of Major L'Estrange was so particularly remarked by me during the whole of the action that I feel it to be my duty to state the same in the warmest terms.'

Looking for easier targets, and perhaps 'drunk with victory' with the thought of an open Spanish line to attack a small group of some thirty or forty lancers penetrated beyond the 31st and attacked Marshal Beredford and General Zayas together with their respective staffs between the two other brigades of British 2nd Division and the Spanish line to their front.

One Polish Lance made straight for the Allied Army Commander, but took on more than he bargained for with Beresford's physical prowess;

'One of them grabbed the marshal by the collar, but Beresford lifted him from his horse and threw him to the ground where he was killed.'

The French cavalry charge had been devastating for Colborne's brigade but, after it had run its course, still left the other two brigades of British 2nd Division behind the Spanish line and with French V Corps shot up and held in front of them.

At this point both sides took the opportunity to perform a passage of lines with the French 2nd Division moving through their battered comrades and the Spanish line ordered to retire through the ranks of the British battalions in their two deep lines, not before voicing their reluctance and with the British troops having to elbow their way through the 4th battalion Spanish Royal Guards, justly proud of their stand and unwilling to pull back.

The fighting then went into a second round of musketry that mimicked the first but this time with General de Brigade Maransin's 2nd Division trying to charge home against a British two deep line and, as so many times before, seeing the French columns pull up after having been shot up on the way in and then trying to shake out into line.

However unlike the attack of Colborne's brigade, the classic British tactic of following up a successful volley with a bayonet charge was not carried out, and Dempsey speculates that the early loss of Major General Hoghton during the firefight and the fact that the British line was broken up into battalions fighting individual battles after having passed through the Spanish line may have contributed to the battle degenerating into a battle of attrition with the French columns standing and trading shots with the British line.

To quote Dempsey;

'Unable to exploit their firepower advantage over the opposing columns with cold steel, Hoghton's battalions took extraordinary casualties themselves. The result was a prolonged and bloody stalemate.'

One of the battalions involved in this bloody exchange of fire was the 1/57th Foot under the command of Lieutenant Colonel William Inglis.

The Regiment had never earned a single battle honour up to this point, but the extraordinary tenacity displayed by the regiment 'gave posterity a new exemplar of behaviour for British soldiers facing adversity and earned the immortal nickname of the Die Hards'*

The battalion started the day with 647 rank and file and finished it with just 219 survivors, a loss of 66% including Colonel Inglis, with the regimental history stating;

'Colonel Inglis ... was severely wounded ... but, refusing all offers to carry him to the rear, he remained where he had fallen, in front of the colours of his regiment, urging his men to keep up a steady fire and die hard.'

There is a full and extensive examination offered by Dempsey in Appendix D of his book on how the 57th earned their title and despite a lack of direct attributable evidence for Colonel Inglis uttering the immortal words I happen to agree that no matter what, the title was fairly won as the casualties bear testament to.

*Direct quote from Demsey

With the battle again degenerating into a stalemate, both commanders were struggling to decide the best course and on which reserves, not yet committed, to use, to swing the battle their way.

It is at this stage that Beresford comes in for the most criticism and accounts suggest that he was not dealing well with the stress of command as his soldiers looked to him for a decisive lead.

Oman picks up the thread in his account of the closing stages of the battle;

'The stroke which ended the battle came from a direction where Beresford had intended to keep to the defensive, and was delivered by the one part of his army which he had refused to utilize—the 4th Division.

|

| Major General Sir Galbraith Lowery Cole |

Cole and his eight battalions had been standing for an hour and a half supporting the allied cavalry, opposite Maubourg's threatening squadrons. He was himself doubting whether he ought not to take a more active part, and sent an aide-de-camp to Beresford to ask for further

orders; but this officer was badly wounded on the way, and the message was never delivered. If it had been, the answer would undoubtedly have been in the negative.

But at this moment there rode up to the 4th Division Henry Hardinge, then a young Portuguese colonel, and Deputy Quartermaster-general of the Portuguese army. He had no orders from Beresford, but he took upon himself to urge Cole to assume the responsibility of advancing, saying (what was true enough) that Hoghton's brigade on the heights above could not hold out much longer, and that there were no British reserves behind the centre.

Cole hesitated for a moment—the proposal that he should advance across open ground in face of 3,500 French cavalry, without any adequate support of that arm on his own side, was enough to make any man think twice. But he had already been pondering over the move himself, and after a short conference with Lumley, his colleague in command of the cavalry, determined to risk all.

The 4th Division was ordered to deploy from columns into line, and to strike obliquely at the French flank. Entirely conscious of the danger from the twenty-six squadrons of French horse before him, Cole flanked his deployed battalions with a unit in column at either end: at the right flank, where Harvey's Portuguese brigade was drawn out, he placed a provisional battalion made up of the nine light companies of all his regiments, British and Portuguese; at the left extremity, on the flank of his British Fusilier brigade—the two battalions of the 7th, and the 23rd Royal Welsh Fusiliers—was a good Portuguese unit—Hawkshaw's battalion of the Loyal Lusitanian Legion.

The line made up 5,000 bayonets—2,000 British, 3,000 Portuguese. The whole of the English and Spanish cavalry advanced on his flank and rear, Lefebvre's horse-artillery battery accompanying

the extreme right.

The sight of this mile of bayonets moving forward showed Soult that he must fight for his life—there was no drawn battle possible, but only dire disaster, unless Cole were stopped. Accordingly he told Latour-Maubourg to charge the Portuguese brigade, while the whole nine battalions of Werle's reserve were sent forward diagonally to protect the flank of the 5th Corps, moving along the upper slope of the heights so as to thrust themselves between the Fusilier brigade and the flank of Girard and Gazan.

Soult had now no reserve left except the two battalions of grenadiers reunis, which he held back for the last chance, on his right rear, keeping up the connection with Godinot.

The French cavalry struck first, but this time the Allied line was ready from them and more particularly Harvey's Portuguese line who received two charges in line as cool as any veterans, as recounted by Sir Charles Vere;

'The French cavalry, under General Latour Maubourg, was in front of the advancing line of the Portuguese infantry during its movement. The French cavalry was received with, and repulsed by a well directed fire from the line, and the Artillery on its flanks, in both charges. The line shewed great steadiness; and conduct, that would have done honour to the best and most experienced troops.'

Next it was the turn of the Fusiliers in Colonel Myers brigade to take the fight to the flank columns of Marasin's French 2nd Division as recounted by Lieutenant Colonel Sir Edward Blakeney of the 7th Fusiliers;

'We moved steadily towards the enemy, and very soon commenced firing. The men behaved most gloriously, never losing their ranks, and closing to the centre as casualties occurred.

From the quantity of smoke, I could perceive little but what was immediately to my front. The first battalion (of the 7th) closed with the right column of the French, and I moved on and closed with the second column, and the 23rd with the third column.'

He went on to describe the French reaction to the British fire;

'I saw French officers endeavouring to deploy their columns, but all to no purpose; for as soon as a third of a company got out (of the column) they immediately ran back, to be covered by the front of the column.'

The time had come to avoid the previous stalemated firefights by initiating the charge of bayonets as one officer of the 23rd Fusiliers recounted;

' ... we advanced to within about twenty paces of them without firing a shot. When our men gave three cheers and fired, the enemy broke in confusion.'

The Spanish battalions joined in the advance as recounted by Ensign Benjamin Hobhouse of the 57th Foot recounted in a letter to his father describing General Ballesteros using a bloody French general's coat;

'Ballesteros seized it and cried out, though I believe he knew to the contrary, 'Soult is dead my lads, look at his coat,' as he rode in front of the lines, and he held up an embroidered coat.

He said in my hearing, and it produced an admirable effect; for both Spaniards and British advanced to the attack with redoubled vigour.'

|

| A local tribute to a British soldier who fell at Albuera erected by his family in Topsham, Devon as pictured in my previous post. Lieutenant Colonel George Henry Duckworth |

Oman summed up the final Allied attack;

'The fusiliers lost more than half their numbers—1,045 out of 2,015 officers and men. Their gallant brigadier, Myers, was among the slain. Werle's three regiments had casualties of well over 1,800 out of 5,600 present—a bigger total but a much smaller percentage—one in three instead of the victors one in two.

The rout of the French reserves would have settled the fate of the battle in any case; but already it was won on the summit of the plateau also. For at the same moment when the Fusiliers closed, Abercrombie's brigade had wheeled in upon the right of the much-disordered mass that represented the 5th Corps, and, when they followed up their volleys with a charge, Girard's and Gazan's men ran to the rear along the heights, leaving Hoghton's exhausted brigade lying dead in line in front of them. The fugitives of the 5th Corps mingled with those from Werle's brigade, and all passed the Chicapierna brook in one vast horde.

There was practically no pursuit: Latour-Maubourg threw his squadrons between the flying mass and the victorious Allies and the British and Portuguese halted on the heights that they had won ....

|

| My rendition of the Vistula Lancers prepared for Talavera 208 and ready to take the field in a future Albuera play through |

So finished the fight of Albuera; a drenching rain, similar to that which had been so deadly to Colborne's brigade, ended the day, and made more miserable the lot of the 10,000 wounded who lay scattered over the hillsides.

The British had hardly enough sound men left in half the battalions to pick up their own bleeding comrades, much less to bear off the mounds of French wounded, who lay along the slopes of the gentle dip where the battle had raged hardest. It was two days before the last of these were gathered in.'

From an Allied army of just over 35,000 men, casualties are estimated at 6,000 to 7,000, whilst the French, starting with some 24,000 are thought to have lost somewhere between 6,000 to nearly 8,000, however grand totals don't go anywhere to capture the horror of individual units losing 60 -75% casualties, whilst others walked away from the encounter practically untouched.

The battle and the losses suffered seems to have seriously shaken both Beresford and Wellington’s confidence in him, and the latter would be very unhappy reading the after action report of the battle, commenting to a staff officer;

‘This won’t do, It will drive the people in England mad. Write me down a victory.’

Soult tried to minimise the losses in his report to the Emperor, trying hard to cover up the fact that it was he that relinquished the field of battle, but generously paid tribute to the tenacious steadfastness of the Allied troops writing later;

‘There is no beating these troops, in spite of their generals. I always thought they were bad soldiers, now I am sure of it. I had turned their right, pierced their centre and everywhere victory was mine - but they do not know how to run.'

A soldier of the 71st visited the battle site in 1812 and was shocked at the sight;

'When I first came upon the spot where the battle of Albuera had been fought, I felt very sad; the whole ground was still covered with the wrecks of an army, bonnets, cartridge-boxes, pieces of belts, old clothes, and shoes; the ground in numerous ridges, under which lay many a heap of mouldering bones. It was a melancholy sight; it made us all very dull for a short time.'

|

| My rendition of the 3rd Buffs for Talavera 208, similarly ready for their rematch with the Vistula Lancers pictured above. |

A soldier of the 71st visited the battle site in 1812 and was shocked at the sight;

'When I first came upon the spot where the battle of Albuera had been fought, I felt very sad; the whole ground was still covered with the wrecks of an army, bonnets, cartridge-boxes, pieces of belts, old clothes, and shoes; the ground in numerous ridges, under which lay many a heap of mouldering bones. It was a melancholy sight; it made us all very dull for a short time.'

Speaking personally, standing on the edge of Albuera field and knowing the events that occurred there, was a moving experience and it was nice to see the information board close by highlighting the battle to any casual visitor that might happen by and be interested enough to stop and read.

Principle References used in this post:

Albuera 1811 The Bloodiest Battle of the Peninsular War - Guy Dempsey

Albuera, The Fatal Hill - Mark S Thompson

History of the Peninsular War Vol IV - Sir Charles Oman

Soldier of the 71st

Recollections of the Peninsula - Moyle Sherer

Marches, Movements and Operations - Sir Charles Vere

Next up, I should be back from a week away in Spain getting a bit of autumn sun to start work on the next post in the series looking at the pivotal battle of Bailen, together with some pictures of my Indians and Butlers Rangers added to my AWI collection.

As always lots of lovely pics that help you understand the action and the terrain fought over.

ReplyDeleteThanks Steve, some parts of battlefields can end up as a series of pictures of fields unless you can get some context for them to allow the viewer to picture what happened there. I hope I have struck a balance.

DeleteJJ

Another great report. On my to see list.

ReplyDeleteThanks James, I think we all have similar lists!

DeleteJJ

Excellent series of battlefield visits and a fitting last one. Albuera has changed a lot since were there, and very much for the better. It's good that many of the battlefields you visited now have memorials and information centres. On our visits most has nothing to show a major battle had taken place. Perhaps it is because Spain was the scene of so much fighting through the ages that they make so little effort to present the battlefields to visitors.

ReplyDeleteI have really enjoyed reading your reports. They brought back many happy memories of our own visits. We also took photocopies of personal descriptions of each battlefield, which greatly adds to the enjoyment and understanding of the location.

Good job, very well done

Thank you Paul, the site of the battle out on the Allied right flank took a bit of finding to determine exactly which part of the slope the French came along, and I worked it out before noticing the display board and sign, which was reassuring.

DeleteThe signing of the various battle sites is still a bit hit and miss and I get the feeling that apart from Bailen the Spanish battle sites are all but ignored with two, Burgos and Gevora outside Badajoz, built over.

One area where I think the Spanish excel is with the models of Albuera and Badajoz which are stunning examples of the art and something that puts some of the shoddy examples displayed in many British military museums to shame, the Perry's model of Agincourt excepted.

It would be nice to see a commitment to that way of portraying famous battles to a younger generation who are more likely yo take an interest through a better visual portrayal alongside the copious amounts of military memorabilia and I think the National Army Museum in London for example would be spending their money more profitably taking a similar approach and we certainly have the model making talent in the UK to produce them.

Thanks again

JJ

Great post and great photos. Thanks to share

ReplyDeleteExcellent job Thankyou.

ReplyDeleteThank you, glad you enjoyed the read.

DeleteJJ