Corunna Retreat - Peninsular War Tour 2019

Battles and Actions in the Tagus Valley(Alcantara and Almaraz Bridges) - Peninsular War Tour 2019

Battles and Actions in the Tagus Valley, Battle of Talavera - Peninsular War Tour 2019

I thought my second post in this series, covering the Battle of Salamanca, was long, but this one looking at the four sieges of Badajoz is, by the nature of the depth of content, much longer; and with the number of British memoirs covering the third siege in particular, demanded a proper consideration of the hell many of the soldiers involved went through, perhaps something that would not be seen in a much larger way until the trench warfare of World War One.

I wanted this post to serve as much as anything, as my tribute to those men, given that Carolyn and I only had to contend with the discomfort of temperatures in the early forties degrees centigrade, on the afternoon of our visit; and given the loss of much of the original defence works to later twentieth century development, the model of the 1812 breach and assault makes a good stand in to accompany the testimonies of the soldiers who did it for real.

If you set yourself the task of following my text, then I can only say you must be slightly mad, but thank you and I hope I have done the subject justice.

-------------------------------------------

With our touring of the valley of the River Tagus completed with a visit to Talavera, Carolyn and I headed south-west and moved our lodgings from Trujillo to just north of Elvas, back on the Portuguese/Spanish border to take time to look at this important area in the southern theatre of operations for Wellington's army.

The border here is dominated by the mighty River Guadiana, a river I once swam in in my youth during a hot summer holiday to southern Portugal and the Algarve. The river's course reaches the border after meandering its way across central Spain, before swinging south to meet the Mediterranean Sea and here at the bend in the river is situated the walled fortress city of Badajoz.

The city, perched above its glorious Roman arched bridge over the Guadiana was the other 'Key to Spain' as mentioned in my look at the similarly dominant walled fortress of Ciudad Rodrigo in the north.

The area has been occupied since the Bronze Age, about 4000 BC, but the city itself traces its founding back to the 8th century AD as, during Roman times, the area was dominated by the great Roman city of Merida. It was the Moorish Umayyad dynasty that raised Badajoz importance as a regional centre, up until the early 11th century, and its Moorish castle stands out as a key feature of its remaining walled defences.

With the 'Reconquista' and the expulsion of the Moors, the city became central to the disputed region between Portugal and Spain and would see its position countered with the development of another former Moorish stronghold, Elvas in Portugal, and also by the fortified town of Campo Mayor to the north.

|

| A view of Badajoz with Allied troops in the foreground and the road from Elvas crossing the Roman bridge and the white Las Palmas Gate visible on the opposite bank. |

As well as the key border cities and towns, the wider territory of Estremadura would host the activities of Marshal Jean de Dieu Soult as, from early 1810, he set out to carve out his own vice-royalty under the pretence of pursuing the Emperor's orders of subduing this southern region in the name of the Emperor's brother, King Joseph.

|

| Marshal Jean de Dieu Soult |

These activities would see him fail to destroy the central Junta, then meeting in Seville and fail to stop them making a hasty retreat to Cadiz which would see his troops under Marshal Victor pursue a lengthy but ultimately failed siege of the city; all the while attempting to subdue Spanish regular and irregular forces and occasional incursions by Anglo-Portuguese forces after having failed to bring any worthwhile support to Marshal Massena in his mission to invade and occupy Portugal, other than to take the city of Badajoz which he would fail to hold on to in 1812 when the tide of war had irrevocably turned against the French.

At the end of 1810 Napoleon was troubled by the news he was getting from the free press in England that Massena's invasion of Portugal was stalled before the defences around Lisbon and that the Spanish general La Romana had pulled his army back over the border from Estremadura to aid Wellington in his defence of the country.

Marshal Soult soon was made aware of his Emperor's displeasure at his failure to detain La Romana and his army, as per his orders when he was sent into the area at the start of the year and, desperate to reconcile the situation, he offered to conquer Estremadura.

The offer entailed the Marshal having to supplement Mortier's Corps of 13,000 men in and around Seville, with another 7,000 men drawn from his Andalusian army; seeing half of Marshal Victor's cavalry, then supporting his operation besieging Cadiz, withdrawn, and a regiment taken from Sebastiani, chasing partisans in the Sierra de Ronda, together with the 63eme Ligne also taken from Victor and as many guns as possible collected from numerous fortresses to put together a siege train, all to be gathered at Seville in January 1811 in preparation for the venture.

The plan was to advance in two columns over the Estremaduran plains to Badajoz and there to lay siege to the city, however things soon went wrong, as hindered by heavy seasonal rains, the 2,500 oxen towing the thirty-four gun siege train died and the Spanish drivers deserted en masse leaving the guns stranded in the pass of Monasterio, between Seville and Badajoz (see map above).

To make matters worse the train was threatened by a Spanish army to the west under General Ballesteros near Fregenal which required the Marshal to detach Marshal Mortier and half of his force to drive the Spanish back over the Portuguese border after a well fought rearguard by the Spanish commander.

As Mortier drove off Ballesteros, leaving General Gazan to pursue the Spanish while Mortier himself, rejoined Soult's main force, Soult managed to press on and arrived before the small fortress town of Olivenza on the 11th January, a dilapidated work that could not be allowed to stand in the French rear and required twelve days to batter a breach that forced General Herck and his 4,000 man Spanish garrison together with a battery of guns to surrender on the 23rd January.

The fall of Olivenza required a detachment of two battalions to escort the prisoners away which, added to the troops under Mortier chasing Ballesteros, left Soult with just 5,500 infantry. To add to his woes, the Emperor's orders arrived for him to press on with his campaign to support Massena urgently and thus he felt compelled to advance on Badajoz, hoping that his efforts would draw in La Romana's army to the aid of the city and go some way to appease the Emperor.

Thus Soult arrived with his siege train and his small army before Badajoz on the 26th January 1811.

|

| General Rafael Menacho, Spanish Governor of Badajoz, commanded a garrison of some 5,000 men and 150 modern guns |

The city was under the command of General Rafael Menacho and like his compatriot in the north, General Herasti was an honourable and capable man commanding an equally capable garrison of 5000 men supported by 150 guns.

With the north side of the city covered by Fort San Christobal and the river and stream, the most obvious place to attempt to attack was the area between the Padaleras Fort and the riverbank, but Soult's small infantry force rendered this option liable to attack from Spanish artillery from the north bank. Thus Soult and Mortier agreed that the initial attack should focus on capturing Fort Paderleras.

|

| General Menacho's arrival in Badajoz in 1810, via the Puerta del Pilar, close to the Santa Maria Bastion as indicated on the map of the fortification above. Model by Curro Agudo Mangas and displayed in the Luis de Morales Museum in Badajoz https://modelismoprofesionaldeescenas.blogspot.com/ |

|

| This model and another showing the great breach in 1812 gives a great impression of the original ditch that has since been removed and built over |

Work commenced on the 28/29th January to create the first parallel, approach trenches and saps that were completed on the 30th prompting vigorous attacks from the Spanish garrison, seeing Soult's chief engineer officer and a number of sappers together with the leader of the sortie, Colonel Bassecourt of the 1st Sevilla Regiment killed in the fighting.

On the 3rd of February as the weather improved General Gazan arrived with the balance of Soult's infantry, back from chasing off General Ballesteros and within hours were in action ejecting a second Spanish force that had gained access to the French trenches.

On the following day Soult brought up two batteries of guns and started to bombard the town with, it seems, little effect.

Meanwhile, aware of Soult's moves into Estremadura, Wellington and La Romana had prepared to send reinforcements to the beleaguered city by assembling an army of 14,000 men including some Portuguese cavalry under General Madden, initially to be commanded by La Romana himself until his sudden death on the 23rd January forced a change in command to General Gabriel de Mendizabal.

|

| General Gabriel de Mendizabal Iraeta |

Mendizabal was given clear instructions on how he was to use his 14,000 men but chose to execute his own plan after arriving on the heights of Cerro San Christobal on the 5th of February by inserting the bulk of his infantry and Madden's cavalry into the city via the bridge, whilst fending off Latour-Maubourg's dragoons who attacked to the foot of the Christobal ridge and were forced to fall back.

With a large force of Spanish troops in the city a plan was executed to attack Soult's lines and on the 7th a large force of 5,000 men under the command of General Carlos de Espana, emerged from the Trinidad Gate at three o'clock in the afternoon and attacked General Phillipon's brigade atop the Cerro de San Miguel, destroying three batteries and holding the trenches from repeated counter-attacks from the 34e and 40e Ligne until eventually forced back into the city by a French flank attack that threatened their retreat route back there.

The next day Mendizabal withdrew his two divisions from the city and encamped on the heights of San Christobal but, despite advice from General Menacho, took no steps to strengthen the position with trenches.

On the 11th February Soult turned his attention back to the siege with a determined attack by escalade against Pardaleras Fort which against the odds, fell to the French attack causing Menacho to turn his guns against it and forcing the French garrison to construct their own communication trench from it back to their own lines.

|

| Marshal Edouard Mortier |

A return of bad weather had raised the water levels in the river and stream preventing Soult from sending a force across it to confront Mendizabal but this changed on the 18th when water levels dropped sufficiently to allow Mortier to cross with a force of 7,000 men, including an infantry and dragoon division and a brigade of light cavalry.

Oman described the French attack;

'On the afternoon of the 18th it was reported to Soult that both the rivers had fallen, and that the Gebora had again become fordable. He made no delay, and at dusk his striking-force began to cross the Guadiana—the operation was slow, since only two flying-bridges and a few river-boats were available. But at dawn nine battalions, three squadrons, and two batteries were on the north bank, while Latour-Maubourg had come up from his usual post at Montijo with six cavalry regiments more.

The whole force assembled in the angle between the Guadiana and the Gebora amounted to no more than 4,500 infantry and 2,500 horse, with twelve guns, a total so much below Mendizabal's 9,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry that the adventure seemed most hazardous. But fortune often favours the audacious, and on this day Soult chanced on the unexpected luck of a very foggy morning.

He was practically able to surprise the enemy, for the first warning that a battle was at hand only came to Mendizabal when, shortly after dawn, his picket at the broken bridge of the Gebora—a short mile or so in front of the heights—was driven in by masses of French infantry. At the same moment a tumult broke out on his left rear: the 2nd Hussars, sent on by Latour-Maubourg to discover and turn the Spanish northern flank, had been able to mount the heights unseen and unopposed, by making a long detour, and rode unexpectedly into the camp of one of Carlos de Espana's regiments.

Mendizabal's troops flew to arms, and began hastily to form their line upon the heights, but they had no time to get into good order, for the enemy was upon them within a few minutes.'

Oman continues;

'The San Cristobal heights are a most formidable position, two miles of smooth steep slopes with an altitude of 250-300 feet, overlooking the whole plain of the Gebora and with hardly any 'dead ground' in their sides. They form an excellent glacis for an army in position ready to defend itself by its fire, for the assailant must come up the hill at a slow pace and utterly exposed. Cavalry could only climb at a walk, and with difficulty; but Mortier had sent all his horse far to the north, where they ascended, and partly crossed, the range at its lowest point, beyond the extreme flank of the enemy.

|

| The French 2nd Hussars were attached to Latour Maubourg's Dragoon division at the Battle of Gevora 19th February 1811 |

Just at this moment the fog rose, and everything became visible. On gaining the heights unopposed, Briche's light cavalry formed up across them, and commenced to move along the summit towards the Spanish left wing, while Latour-Maubourg, with three dragoon regiments, descended the reverse slope and moved towards the hostile camp, in front of which Butron's Spanish horse and Madden's Portuguese could be seen hastily arraying their squadrons.

It may be said that the battle of the Gebora was lost almost before a shot had been fired, for on seeing themselves threatened in flank and about to be charged by Latour-Maubourg, the Spanish and Portuguese horse broke in the most disgraceful style, disregarding the orders of their commanders, and went off in a disorderly mass across the plain of the Caya, towards Elvas and Campo Mayor.

They outnumbered the enemy, and could have saved the day if they had fought even a bad and unsuccessful action, so as to detain the French dragoons for a single hour. But the cavalry of the Army of Estremadura had a bad reputation—they were the old squadrons of Medellin and Arzobispo, of which Wellington preserved such an evil memory, and Madden's Portuguese this day behaved no better. They escaped almost without loss, for Latour-Maubourg let them fly, and turned at once against the flank and rear of Mendizabal's infantry.

The combat on the southern part of the heights had not yet assumed a desperate aspect. Though the column which was formed by the 100th regiment had got up the hillside under the fort of San Cristobal, and had penetrated into the gap between that work and its extreme left, the Spanish infantry was still holding its own. The fog having cleared, they were able to estimate the smallness of the number of the hostile infantry, and stood to fight without showing any signs of failing. But the fusilade was only just beginning all along the hillside when the victorious French cavalry came into action. Briche's light horse came galloping along the crest of the heights, while Latour-Maubourg's dragoons were visible in the plain behind, well to the rear of the Spanish line.

Mendizabal, horrified at the sight, ordered his men to form squares, not as usual by battalions, but vast divisional squares, each formed of many regiments, and with artillery in their angles. If the French cavalry alone had been present, it is possible that in this formation the Spaniards might have saved themselves. But Mortier's infantry was also up, and well engaged in bickering with Mendizabal's men.

The squares, when formed with some difficulty, found themselves exposed to a heavy fire of musketry from the front at the same moment that the cavalry blow was delivered on their flank. Bridie's hussars penetrated without much difficulty through battalions already shaken by the volleys of the French infantry.

|

| The Hussars of Estremadura part of General Butron's Spanish Cavalry Division of the Army of Estremadura of whom Oman said 'the cavalry of the Army of Estremadura had a bad reputation.' |

First the northern and soon afterwards the southern square was ridden through from the flank and broken. The disaster that followed was complete: some of the Spanish regiments dispersed, many laid down their arms in despair, a limited number clubbed together in heavy masses and fought their way out of the press towards the plain of the Caya and the frontier of Portugal.

General Virues and three brigadiers were taken prisoners, with at least half of the army. Mendizabal and two other generals, La Carrera and Carlos de Espasna, got away, under cover of the battalions which forced their passage through toward the west. In all about 2,500 infantry escaped into Badajoz, and a somewhat smaller number towards Portugal. The rest were destroyed—only 800 or 900 had been killed or wounded, but full 4,000 were taken prisoners, along with seventeen guns—the entire artillery of the army—and six standards.

The French loss, though under-estimated by Soult in his dispatch at the ridiculous figure of 30 killed and 140 wounded, was in truth very small—not exceeding 403 in all. It fell almost entirely on the cavalry—who had done practically the whole of the work. The regimental returns show that only four officers in the infantry were killed or wounded, to thirteen in the mounted arm.'

The defeat at Gevora was a disaster for the Allies, leaving Soult able to tackle the siege of Badajoz, from both sides of the river, at his will.

However General Menacho was determined to resist and French progress was slow with Spanish artillery fire from the walls proving deadly accurate and it was not until the night of the 24th/25th February that Soult was able to deploy two batteries close to the Pardaleras Fort to provide counter fire against the defenders guns.

|

| General Menacho is felled by a French marksman whilst observing the Spanish sortie on the 2nd March 1811 |

By the 2nd of March the French had reached the ditch in front of the San Juan bastion, with a mining operation stopped the next day by another vigorous attack by the garrison, the last to be ordered by General Menacho as he was killed by a chance musket shot as he observed the sortie from the walls above.

Command immediately devolved to General Jose Imaz possessing none of the aggressive and active intent of his predecessor and the French quickly noticed the decline in the intensity of the defence in the days following, with no further sorties made from the walls; allowing them to take full advantage by mining the counterscarp and creating a breach between the Santiago and San Juan bastions that was declared practicable on the 10th March with a summons sent to Imaz to surrender the city that day.

Imaz immediately summoned his council of war, whilst in possession of a message from Wellington via semaphore from Elvas, informing him that General Beresford was on his way with two Allied divisions to relieve the city and knowing this, concealed it from his officers, accepted their majority vote to surrender the place, whilst making a personal declaration against the decision in a feigned display of reluctance on his part.

He surrendered that afternoon and allowed French troops to occupy the Fort of San Christobal and Tete du Point before marching out the next day with 8,000 troops leaving 1,000 sick and wounded in the city hospital.

The city yielded to the French 170 pieces of ordnance, nearly 8,000 tons of powder together with large quantities of infantry cartridges and two complete bridging trains that were perhaps the most valuable prizes of all.

The Regency in Cadiz ordered that Imaz should face trial for his shameful conduct but subsequent hearings dragged on and nothing was concluded by the end of the war.

The retreat of Massena had effectively released Soult of his duty to cooperate with the now failed invasion of Portugal; and with Wellington able to deploy additional forces to Cadiz which were threatening Victor's investment of the place and with Ballesteros back on the border threatening his troops in and around Seville, the Marshal wasted no time to head south on the 2nd March 1811, leaving a small force of 11,000 men under Mortier to garrison Badajoz and to continue the offensive by capturing Campo Mayor, with Mortier heading north on the same day that Soult marched south

The small force left to Mortier posed him quite a challenge, to carry on offensively whilst securing Badajoz, but the month of March would see hem successfully knock out the two Allied fortresses at Campo Mayor and Albuquerque, leaving Latour Maubourg in charge of dismantling them; and retrieving the usable guns and ammunition, before conducting a hasty retreat back to Badajoz in front of a badly organised pursuit by Marshal Beresford, a he approached with 18,000 Allied troops.

This action and the pursuit from Campo Mayor will be covered in a following post.

Following the retreat of Massena and his being driven back over the border into Spain, Wellington turned his attention south, arriving at Elvas on the 16th April 1811, to see the situation for himself, bringing with him his chief engineer, Lieutenant Colonel Sir Richard Fletcher to make a full reconnaissance of the city.

The result of the reconnaissance suggested the main attack to be made on San Christobal, with diversionary attacks against Pardaleras and Picurina, the plan being thought to offer the prospect of a quick result given that Wellington estimated the Allies would only have sixteen days to force a capitulation before Soult would arrive to relieve the city.

Once San Christobal was taken a breach would be battered in the wall of the old medieval castle and once complete, work would cease on the diversionary parallels, and the city stormed before the defenders could effect repairs to the castle wall.

Having agreed the plan, Wellington rode north on the 25th April to rejoin the main army leaving Marshall Beresford in charge of the operation with a comprehensive set of instructions covering his actions in the event of every conceivable French reaction.

|

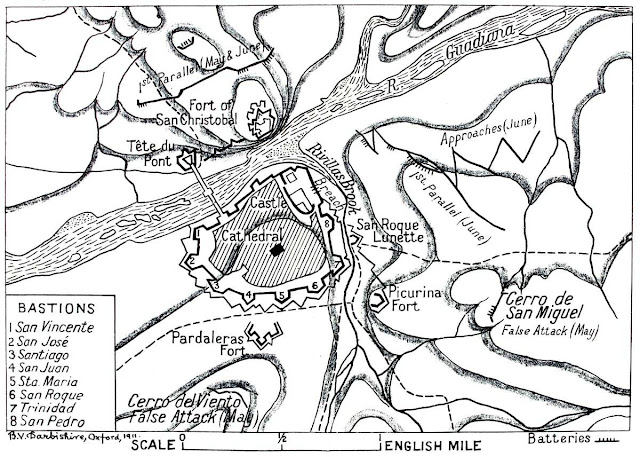

| Oman's map illustrating the key positions and British trenches for the first and second Allied sieges of Badajoz in 1811 |

On the 9th April Beresford crossed the Guadiana at Jerumenha, advancing in two columns and arrived before Olivenza to summon the French garrison to surrender which after a fairly brief resistance capitulated on the 15th March after a practicable breach was made seeing the 460 French troops made prisoner.

The Allies then preceded to surround Badajoz, via Albuera, driving off Latour Maubourg's covering forces and linking up with Castanos and the remnants of the Army of Estremadura who had taken Merida and pushed the French back beyond Almendralejo.

With the circumvention complete, Beresford turned his attention back to Badajoz and with an improvement in the weather on the 5th May, Major General Stewart commenced securing the investment of the city which he declared complete the same day and by 8th of May the first parallels were being dug in front of San Christobal, Pardaleras and Picurina, with the Allies opening the old French works from a couple of months earlier.

Early on the 10th the French launched a sortie from Badajoz over the Roman bridge and via the Tete du Pont entering the battery position in front of Fort Christobal, but were driven back by the trench guard who then got themselves badly shot up by the guns on the walls of the fort when they got carried away in the pursuit, seeing some 400 of them killed or wounded.

Following this attack, Battery No. 4 was started on the western end of the parallel to allow fire to be directed along the bridge from about 700 yards, with three 12 pounder guns ordered up from Elvas to arm it.

|

| Map illustrating the Allied positions thrown up against the Tete du Pont Bridgehead and Fort San Christobal |

However over the next two days the poor quality ancient guns salvaged from Elvas together with inexperienced Portuguese gunners and insufficient troops to labour on the trenches and post guard at the same time, saw the work come to an end and the attack flounder with the Allied batteries losing the dual between them and the French gunners on the walls of Badajoz Castle and Fort Christobal with No.1 battery silenced.

Work continued in front of Picurina and Pardaleras with work commenced on the 13th on a new parallel from which the castle might be breached, but by then news had reached the besiegers of the approach of a French relieving force under Soult seeing the guns and stores sent to the rear on the 14th and the siege brought to an end the following day as Beresford prepared to take a force to meet them.

Captain Moyle Sherer of the 34th Foot wrote of his experiences from this time;

"I regard the operations of a siege as highly interesting; the daily progress of the labours; the trenches filled with men who lie secure within range of the garrison; the fire of the batteries; the beautiful appearance of the shells and fireballs by night; the challenges of the enemy's sentries; the sound of their drums and trumpets; all give a continued charm and animation to the service.

But the duties of a besieging force are both harassing and severe; and, I know how it is, death in the trenches never carries with it that stamp of glory which seals the memory of those who perish in a well-fought field. The daily exploits of the northern Army under Lord Wellington and Graham's victory at Barossa, made us restless and mortified at our comparative ill-fortune."

Captain Sherer would get his 'well-fought field' a few days later at the bloodiest battle of the Peninsular War outside the village of Albuera, fourteen miles south of Badajoz, a battle he, unlike many of his compatriots would survive and one I will cover in a following post.

Following the interruption of the Battle of Albuera fought on the 16th May 1811 and the retreat of Marshal Soult to Seville, Badajoz was reinvested by a Portuguese brigade on the 19th May, probably in accordance with the extensive guidance issued to Beresford from Wellington, prior to the siege.

That same day Wellington arrived with two Allied divisions at Elvas following his own hard fought battle with Marshal Massena at Fuentes de Onoro, earlier in the month, to meet with a somewhat shaken up Beresford and help him 'write up a victory' before sending him back to Portugal to deal with the Regency and training matters, more to his skill set, whilst no doubt relieved to have General Hill returned to him from sick leave in the UK.

Despite the horrendous losses suffered at Albuera the Allied position was a strong one in that both the Armies of Portugal and Estremadura had been themselves roughly handled at Fuentes de Onoro and Albuera respectively, leaving Wellington a period of time to focus his efforts on retaking Badajoz before either would be ready to intervene.

However the weakness in siege artillery was to prove a fatal flaw in Allied hopes despite the best efforts of Wellington's chief artillery commander Captain Alexander Dickson who had scoured Elvas for suitable pieces and had assembled thirty 24 pounders, four 16 pounders and four 10 inch and eight 8 inch howitzers; supplemented with six modern iron Portuguese ship guns brought up from Lisbon, together with a company of British artillerymen to provide a core of trained gunners to support their Portuguese allies.

The situation with the guns was only aggravated by the lack of suitable carriages making it difficult to move the pieces to and from Elvas as required.

Wellington took personal command of the next phase in the siege and decided to follow the original plan but to use a greater number of guns in a counter-battery role and to construct many more works to protect the besiegers against sorties.

Most significantly he proposed to press the works simultaneously with equal determination to sufficiently confuse the defenders as to where he intended to breach and assault the city at the very last possible moment.

|

| Map illustrating the Allied parallel and gun positions erected before the castle during the second Allied siege |

By the 6th of June in spite of drooping gun barrels among the Allied 24 pounders and the reduced rate of fire it caused, and the accurate French return fire dismantling several pieces, the Allied gunners had succeeded in causing a minor breach to the castle but a feasible one to San Christobal which was assaulted at midnight by 180 men and a Forlorn Party led by Ensign Dyas and twenty-five soldiers from the 51st Foot, guided by Lieutenant Forster, an engineer officer.

However the scaling ladders were found to be two short to scale the seven foot drop from the wall to the rubble slope in the ditch, made worse by French work parties removing some of the rubble and filling the breach with carts and other obstacles.

|

| The Forlorn Hope Party for the attack on Fort San Christobal at midnight on the 6th June 1811 was composed of 26 men and an engineer officer from the 51st Foot. |

Dyas and Forster then made the sensible decision to withdraw just as Major Mackintosh plunged into the ditch with the main body to see the attackers showered in shells, grenades, rocks and other missiles killing or wounding about a hundred of them, including Lieutenant Forster, before they could withdraw.

That same night seven iron 24 pounder guns were brought up to reinforce Battery No. 7 and they commenced firing on the 8th with a noticeable improvement in the rate of fire and the effect on the clay at the foot of the wall which started to crumble and threaten a likely collapse.

Indeed further fire over the next few days would render the castle breach to be declared practicable, but San Christobal needed to be taken first and with further fire directed against its breech a second attack was launched on the 9th June.

This second attempt would see a similar twenty-five man forlorn, again led by Dyas, lead a seventy five man assault group into the breach but also supported by parties detailed to cut the fort off from rearward support and another similarly sized party to escalade the front walls of the fort and to provide close covering fire with muskets and rifles against defenders atop the parapet.

The assault however was met by a tremendous fire from the garrison, obviously reinforced in anticipation of a second attempt, and despite persisting for an hour, command and control was lost, with the death of many of the officers involved and the attackers withdrew leaving one-hundred and forty men killed or wounded, nearly seventy percent of the force.

Private Wheeler of the 51st was cut off in a ditch when the French made a sortie from the fort and evaded capture by soaking his white haversack in the blood of a man killed close to him, convincing the French he was badly wounded in the hip and thus leaving him where he lay after relieving him of shirt, boots and stockings. He recalled;

".... The moon rose which cast a gloomy light around the place. Situated as I was this added fresh horrors to my view, the place was covered with dead and dying, the old black walls and breach looked terrible and seemed like an evil spirit frowning on the unfortunate victims that lay prostrate at its feet.

As the moon ascended it grew much lighter and I began to fear I should not be able to effect my escape, for the enemy kept a sharp look-out and if anyone endeavoured to escape they were sure to discharge a few muskets at him.

I soon perceived that when our batterys fired they would hide behind the walls. I made the most of this by sliding down as often as I observed a flash from our works. By daybreak I had got to the plain below the fort. I had nothing to do but to have a run for it across the No. 1 Battery.

This plain, like our camp, was covered with small dry thistles. The enemy discharged two guns loaded with roundshot, and several muskets at me, and I bounded like a deer, the Devil take the thistles. I felt none of them until I was safe behind the battery."

On his successful return to the Allied lines he was astonished to see Ensign Dyas,

"... without cap, his sword was shot off close to the handle, the sword scabbard was gone and the laps of his frockcoat was perforated with balls."

Ensign Dyas was promoted to Lieutenant, replacing one of the other officers of the 53rd killed in the attack, but no other recognition for his undoubted bravery.

At 10 am the next morning the Allies asked for a truce to recover their dead and wounded which was granted and this effectively marked the end of the second siege, with the approach of Marshal Marmont, the newly appointed commander of the Army of Portugal, putting any further work at great risk, and forcing the Allies to lift their blockade on the 16th June and seeing the French relieve the city on the 19th June.

The first and second Allied sieges of Badajoz revealed how much Wellington and his army had to learn about conducting siege warfare, a fact that would still be outstanding during the sieges of Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajoz the following year, but that those lessons were impressing themselves upon the Allied commander, in this his first test, are obvious in the changes observed during the second siege and what would happen in 1812.

Most significantly, Wellington already started to show his recognition of the need to stretch the French defences with multiple assaults as was demonstrated with his unsuccessful second assault on San Christobal, defeated by his not securing the place first, from a reinforcement after the first attack.

In addition he sees the value of supporting his assaults with mass skirmish fire to suppress the defenders during an assault something most notable in the sieges of 1812 and only introduced here on the second attack on San Christobal.

Finally he will deal with the problem of an adequate siege train by bringing in modern artillery from Britain and Lisbon that will enable him to create breaches more quickly and effectively.

However 1812 will reveal another ongoing weakness in British and Allied siege techniques in their need to create a professional engineer and sapping formation skilled in the techniques of preparing entrenchments and gun positions in the best positions to effect the breaches required.

As mentioned in my post looking at the Allied siege of Ciudad Rodrigo, the initiative in the Peninsular War had shifted irretrievably in favour of the Allies with the Emperor's decision to invade Russia in 1812 and Wellington took steps to take full advantage of the effects that decision was already having on the French armies before him; with his well informed intelligence network allowing him to take the prerequisite steps to create the best possible circumstances for when he took the offensive into Spain either against Marmont's Army of Portugal or Soult's Army of Andalusia that summer.

In fact his planning in the winter of 1811 allowed him to take the offensive as early as January 1812 with his bold advance and capturing of Ciudad Rodrigo that month, not only taking the key fortress but capturing the French siege train within it and Marmont's only hope of taking it back.

With one of the key fortress cities dealt with, Wellington could now focus his attention towards Badajoz and by the 18th February 1812 the Allied divisions started to march south one by one, leaving only the 5th Division and Alten's cavalry brigade around Rodrigo when he, in company with them, marched on Badajoz, setting up his new headquarters in Elvas on the 12th March.

On the 8th March a fifty-two gun siege train had been assembled by Alexander Dickson which included twenty recently acquired Russian 18 pounder guns brought in by Admiral Berkley and the Royal Navy, with one problem in that the ammunition was a different calibre to the British 18 pounders, and Berkley refused to exchange the guns from his own ship as a replacement.

Fortunately the ever resourceful Dickson discovered a store of suitable Russian ammunition, although it seems many of the guns were still found to be unsuitable and left behind.

As with the preparation for Ciudad Rodrigo, a similar effort had been initiated for Badajoz with the garrison of Elvas employed in the preceding months in producing gabions and facines in preparation for the planned operation.

|

| Men of the Royal Military Artificers part of the corps that would amalgamate with the Royal Engineers after the experience of siege warfare in the Peninsular War |

As well as guns and stores, Wellington now had at his command 300 British and 500 Portuguese artillerymen, however the engineer arm still remained the weak point with Colonel Richard Fletcher only able to command 115 men of the Royal Military Artificers later supplemented by a party sent up from Cadiz in the closing days of the siege, but with no trained miners and only 120 soldiers from 3rd Division who came with experience working on the trenches at Rodrigo.

|

| Wellington proposed the creation of a corps of sappers and miners based on his experience of conducting siege warfare |

This lack of trained engineering support prompted Wellington to write to Lord Liverpool suggesting a permanent unit should be created as soon as possible;

'I would beg to suggest to your Lordship the expediency of adding to the Engineer establishment a corps of sappers and miners. It is inconceivable with what disadvantage we undertake a siege, for want of assistance of this description.

There is no French corps d'armee which has not a battalion of sappers and a company of miners. We are obliged to depend for assistance of this sort upon the regiments of the line; and although the men are brave and willing, they want the knowledge and training which are necessary.

Many casualties occur, and much valuable time is lost at the most critical period of the siege.'

|

| Position 1 on the Oman Map of the Allied Siege in 1812. The San Vincente Bastion assaulted by Walker's brigade, 5th Division |

As bad as the engineering position was the prospects in other regards were favourable towards prosecuting the siege, with Soult still detained before the siege lines around Cadiz and his policing of Grenada making it unlikely that he could gather more than 25,000 men to oppose the siege and that, in not less than a few weeks, needed to gather them. Even then Wellington could meet him in battle with 40,000 troops and still leave 15,000 investing Badajoz.

Marmont was in a better position to intervene if he gathered in his five or six divisions in and around Salamanca, as he had done in June 1811, but Wellington could likely count on three to four weeks of uninterrupted operations before the French could intervene; and as it later transpired the Emperor had forbade Marmont to move, only granting him permission on the 27th of March, by which time it was too late.

However this still presented Wellington with a time problem, demanding the city should be taken by the first week of April, the earliest time a relief attempt could be made, thus on the 16th March 1812 the 3rd, 4th and Light Divisions crossed the Guadiana to the south of the city via a pontoon bridge; and pressing on via the Cerro del Viento and on to the Cerro de San Miguel and, meeting no opposition, the city was soon invested and cut off from the other French armies.

General Phillipon's garrison at this time consisted of about 4,000 men with a further 400 laid up in the hospital, and consisted of troops from the 9e and 28e Legere, 58e, 64e, 88e and 103e Ligne, the Hesse Darmstadt Regiment and elements from King Joseph's Spanish Guard, 21e Chasseur a Cheval, 26e Dragoons together with artillerymen to man the city guns.

On the evening of the 17th March ground was broken by 3,000 troops digging in about a thousand yards in front of the Picurina fort without any interference from the small French garrison, and under harassing fire from the fort and the city wall the parallel was extended 450 yards to reach the Talavera road on the 18th March.

|

| The early months of 1812 were characterised by atrociously rainy weather that was to make conditions on the march to and during the siege of Badajoz miserable for the Allied troops |

Captain John Kincaid recounted his experiences on the first night's work;

"On the 17th of March, 1812, the third, fourth, and light divisions, encamped around Badajos, embracing the whole of the inland side of the town on the left bank of the Guadiana, and commenced breaking ground before it immediately after dark the same night.

The elements, on this occasion, adopted the cause of the besieged; for we had scarcely taken up our ground, when a heavy rain commenced, and continued, almost without intermission, for a fortnight; in consequence thereof, the pontoon-bridge, connecting us with our supplies from Elvas, was carried away, by the rapid increase of the river, and the duties of the trenches were otherwise rendered extremely harassing. We had a smaller force employed than at Rodrigo; and the scale of operations was so much greater, that it required every man to be actually in the trenches six hours every day, and the same length of time every night, which, with the time required to march to and from them, through fields more than ankle deep in a stiff mud, left us never more than eight hours out of the twenty-four in camp, and we never were dry the whole time.

One day's trench-work is as like another as the days themselves; and like nothing better than serving an apprenticeship to the double calling of grave-digger and game-keeper, for we found ample employment both for the spade and the rifle."

Work in the trenches in such miserable conditions was only made worse by the horrors of war as men attempted to relieve the depressing situation with touches of bravado as described by Sir James McGrigor on a visit to the trenches and to some of his acquaintances in the 88th Connaught Rangers with whom he breakfasted;

"We were very soon obliged to creep on all fours as we advanced, for there were sharp-shooters on the look out, who popped at every head that appeared, and who, as it seems, were good marksmen, for they had killed many of our men in this way.

Under the care of my friend Thomson, we returned in safety; but what was my horror when, in less than two hours after this, an officer of the 88th came to me with the information that our poor friend Thomson had been shot through the head, while engaged with a friend in the same manner as he had but so lately been with me.

An officer of another regiment had called upon him immediately after his return from the trenches with me, and had also expressed a wish to see the state of the trenches; Thomson offered to accompany him, and they had proceeded but a short way, when Thomson, in bravado, stood up, looking directly at the spot from whence the shot came every now and then, believing he was out of reach, when he was struck on the head by a bullet, and fell dead."

|

| Position 1 on the Oman Map of the Allied Siege in 1812. A sally port at the base of the bastion and its adjoining wall |

On the 9th March the work progressed beyond the Talavera road prompting Governor Phillipon to launch his first sortie against the trenches, sending out two battalions of 500 men and an escort of 40 dragoons from the Trinidad gate under the command of General Vieland.

Sergeant William Lawrence of the 40th Foot left an account of his experience during this attack;

"... but on the 19th of March the garrison attacked us, and were only driven back with a loss on our side of a hundred men killed and wounded, and a still greater loss on their part.

I killed a French sergeant myself with my bayonet in this action. I was at the time in the trenches when he came on the top and made a dart at me with his bayonet, having, like myself, exhausted his fire; and while in the act of thrusting he overbalanced himself and fell.

I very soon pinioned him to the ground with my bayonet, and the poor fellow soon expired. I was sorry afterwards that I had not tried to take him prisoner instead of killing him, but at the time we were all busily engaged in the thickest of the fight, and there was not much time to think about things. And besides that, he was a powerful-looking man, being tall and stout, with a beard and moustache completely covering his face, as fine a soldier as I have seen in the French army, and if I had allowed him to gain his feet, I might have suffered for it; so perhaps in such times my plan was the best - kill or be killed."

The actual losses were 20 killed and 147 wounded on the French and around 200 British casualties including the chief engineer Colonel Fletcher, struck by a musket ball in the groin that forced a dollar-piece from his purse an inch into his thigh; in addition the attack was made worse by the loss of two-hundred badly needed entrenching tools taken away by the attackers.

With the sortie repulsed, work continued to extend the trenches under a continuous hail of shot and musketry, with the French garrison, as at Ciudad Rodrigo, using the high points of the city to observe Allied movements of troops within them, signalling with church bells to initiate an increased barrage of shot directed on a point at any given moment.

Captain James MacCarthy of the 50th Foot related his experience of this tactic during a changeover of working parties;

"The working party was retiring to make way for the relief, and the last man stood by my side waiting his turn to pass out, (alternately) and hesitating to allow me to precede him, I desired him to pass, as I was not going; at that instant, a cannon shot (lobbed according to the soldiers' phrase) fell upon him, and tore out his intestines entire, from his right breast to his left hip, and they hung against his thighs and legs as an apron - instantly he lost his balance and fell."

Detailing two men to bury the man, MacCarthy sat down with two engineers to observe the shells being thrown at the works, when one of the men shouted a warning;

"A shell is coming here, sir. I looked up, and beheld it approaching me like a cricket ball to be caught; it travelled so rapidly that we had only time to run a few paces, and crouch, when it entered the spot on which I had been sitting, and exploding, destroyed all our night's work."

The Allied workers took steps to try and alert their comrades to the danger with some Portuguese artillerymen detailed to keep watch on the city and call out whenever a shell was coming.

The shout indicating a single shell heading their way would be 'bomba, balla, balla, bomba,' and on seeing a general salvo from a battery, they would scream 'Jesus, todos! todas!'.

By March 20th the parallel had been extended to the left covering the Seville Road and to the right where work commenced on the construction of batteries 4, 5 and 6, countered by Phillipon, having two guns deployed close to Fort San Christobal, on the opposite bank of the Guadiana, to fire in enfilade along the works, with protection constructed around them to prevent Allied riflemen sniping at the crews.

To counter the French battery, Wellington ordered Leith's 5th Division to move forward and invest Badajoz from the north bank of the river.

By March 25th, all was ready to commence the assault on La Picurina with ten 24 pounders, eleven 18 pounders and seven 5.5 inch howitzers, supplemented by rifle armed marksmen amid the trenches, commencing a galling fire from 150 yards, on the works and forcing the French garrison to abandon the parapet, and seeing return fire delivered from the guns inside the fort and from Badajoz city wall.

The parapet of La Picurina was about twelve feet thick but was severely damaged by the Allied gunfire seeing urgent repairs made to it that evening with the application of facines and woolpacks to shore it up.

Despite the work, the French still needed another day to prepare its defences to resist an assault and alerted of this fact by a Spanish deserter, Wellington gave orders for the assault to be made that night.

|

| Position 4 on the Oman Map of the Allied Siege in 1812. |

The orders for the assault were issued to Major General Kempt commanding the trenches on that sector and detailed 500 men of the 3rd and Light Divisions, formed into three detachments of 200 men on the right and left and 100 in the centre under the commands of Major Shaw, 74th Foot, Major Rudd, 77th Foot and Captain Powis of the 83rd Foot respectively.

|

| The soldiers from the 3rd and Light Divisions were readied for the assault on Fort Picurina on the night of the 25th March 1812 |

Each column would be accompanied by an engineer officer, six carpenters and six miners with cutting tools, crow-bars, hatchets, axes and ladders.

The general plan was to approach the fort with parties detailed to force an entry whilst others moved to the rear to prevent escape or reinforcement from the city walls.

Lieutenant William Grattan of the 88th Foot described the scene;

"At about three o'clock in the afternoon of the 25th of March, almost all the batteries on the front of La Picurina were disorganised, its palisades beaten down, and the fort itself, having more the semblance of a wreck than a fortification of any pretensions, presented to the eye nothing but a heap of ruins. But never was there a more fallacious appearance: the work, although dismantled of its cannon, its parapets crumbling to pieces at each successive discharge from our guns, and its garrison diminished, without a chance of being succoured, was still much more formidable than appeared to the eye of a superficial observer.

It had yet many means of resistance at its disposal. The gorge, protected by three rows of palisades, was still unhurt; and although several feet of the scarp had been thrown down by the fire from our battering-park, it was, notwithstanding, of a height sufficient to inspire its garrison with a well-grounded confidence as to the result of any effort of ours against it; it was defended by three hundred of the elite of Phillipon's force, under the command of a colonel of Soult's staff named Gaspard Thiery who volunteered his services on the occasion.

On this day a deserter came over to us from the fort, and gave an exact account of how it was circumstanced."

|

| Position 4 on the Oman Map of the Allied Siege in 1812. |

Waiting for the signal for the assault to commence, being the firing of a single gun from No.4 Battery, Grattan continued;

"The evening was settled and calm; no rain had fallen since the 23rd; the rustling of a leaf might be heard; and the silence of the moment was uninterrupted, except by the French sentinels, as they challenged while pacing the battlements of the outwork; the answers of their comrades, although in a lower tone of voice, were distinguishable — "Tout va bien dans le fort de la Picurina" was heard by the very men who only awaited the signal from a gun to prove that the response although true to the letter, might soon be falsified.

The great cathedral bell of the city at length tolled the hour of eight, and its last sounds had scarcely died away when the signal from the battery summoned the men to their perilous task; the three detachments sprang out of the works at the same moment, and ran forwards to the glacis, but the great noise which the evolution unavoidably created gave warning to the enemy, already on the alert and a violent fire of musketry opened upon the assailing columns.

One hundred men fell -before they reached the outwork; but the rest, undismayed by the loss, and unshaken in their purpose, threw themselves into the ditch, or against the palisades at the gorge. The sappers, armed with axes and crow-bars, attempted to cut away or force down this defence; but the palisades were of such thickness, and so firmly placed in the ground, that before any impression could be made against even the front row, nearly all the men who had crowded to this point were struck dead.

Meanwhile, those in charge of the ladders flung them into the ditch, and those below soon placed them upright against the wall; but in some instances they were not of a sufficient length to reach the top of the parapet. The time was passing rapidly, and had been awfully occupied by the enemy; while as yet our troops had not made any progress that could warrant a hope of success.

More than two-thirds of the officers and privates were killed or wounded; two out of the three that commanded detachments had fallen; and Major Shawe, of the 74th, was the only one unhurt. All his ladders were too short; his men, either in the ditch or on the glacis, unable to advance, unwilling to retire, and not knowing what to do, became bewildered. The French cheered vehemently, and each discharge swept away many officers and privates.

|

| Position 4 on the Oman Map of the Allied Siege in 1812. |

Shawe's situation, which had always been one of peril, now became desperate; he called out to his next senior officer (Captain Oates of the 88th) and said, "Oates, what are we to do?" but at the instant he was struck in the neck by a bullet, and fell bathed in blood.

It immediately occurred to Oates, who now took the command, that although the ladders were too short to mount the wall, they were long enough to go across the ditch! He at once formed the desperate resolution of throwing three of them over the fosse, by which a sort of bridge was constructed; he led the way, followed by the few of his brave soldiers who were unhurt, and, forcing their passage through an embrasure that had been but bolstered up in the hurry of the moment, carried—after a brief, desperate, but decisive conflict—the point allotted to him.

Sixty grenadiers of the Italian guard were the first encountered by Gates and his party; they supplicated for mercy, but, either by accident or design, one of them discharged his firelock, and the ball struck Gates in the thigh; he fell, and his men, who had before been greatly excited, now became furious when they beheld their commanding officer weltering in his blood. Every man of the Italian guard was put to death on the spot.

Meanwhile Captain Powis's detachment had made great progress, and finally entered the fort by the salient angle. It has been said, and, for aught I know to the contrary, with truth, that it was the first which established itself in the outwork; but this is of little import in the detail, or to the reader.

|

| Ladders that were too short were used instead to bridge the ditch in front of the parapet |

All the troops engaged acted with the same spirit and devotion, and each vied with his comrade to keep up the character of the "fighting division." Almost the entire of the privates and non-commissioned officers were killed or wounded; and of fifteen officers, which constituted the number of those engaged, not one escaped unhurt !

Of the garrison, but few escaped ; the Commandant, and about eighty, were made prisoners; the rest, in endeavouring to escape under the guns of the fortress, or to shelter themselves in San Roque, were either bayoneted or drowned in the Rivillas ; but this was not owing to any mismanagement on the part of Count Phillipon.

He, with that thorough knowledge of his duty which marked his conduct throughout the siege,' had, early in the business, ordered a body of chosen troops to debouche from San Roque, and to hold themselves in readiness to sustain the fort; but the movement was foreseen.

A strong column, which had been placed in reserve, under the command of Captain Lindsey of the 88th, met this reinforcement at the moment they were about to sustain their defeated companions at La Picurina. Not expecting to be thus attacked, these troops became panic-struck, soon fled in disorder, and, running without heed in every direction, choked up the only passage of escape that was open for the fugitives from the outwork, and, by a well-meant but ill executed evolution, did more harm than good."

|

| Position 4 on the Oman Map of the Allied Siege in 1812. The section of the castle wall escaladed by Campbell's Brigade, 3rd Division |

As soon as Phillipon was aware the La Picurina had fallen, he ordered a heavy fire on the fort to prevent the British troops from securing a lodgment in it, but despite French guns firing long after midnight, a communication route was formed into the work from the first parallel and supported on the left by the second parallel.

Total British casualties in the assault amounted to four officers and fifty men killed together with 250 men wounded including Majors Rudd, Shaw and Captain Powys who later died of wounds received, and all three of the engineer guides; whilst the French had about one-hundred men of the garrison killed or wounded and sixty made prisoner including Colonel Thierry.

|

| A sketch of the interior of La Picurina immediately after its capture looking towards Badajoz |

Phillipon was greatly annoyed by the loss of Picurina, having estimated that the fort, following French preparations, which included the provision of a plentiful supply of shells and grenades placed around the parapet and on the glacis, should have held for five to six days; and its disappointing loss might have compelled the French commander to stir the courage of his soldiers by reminding them that a stout resistance and a death for the glory of France was preferable to confinement aboard an English prison hulk.

Despite an attempt by Wellington to garrison the fort, French fire made the place untenable and the place was abandoned the next day after the works inside had been destroyed.

The work of digging further battery positions and sapping towards the San Roque lunette with the intent to destroy the dam holding back water in the inundation of the Rivellas, thus making a crossing there much more practical, continued apace.

|

| Plan of the breaches in the Santa Maria and San Trinidad Bastions |

The work immediately alerted Phillipon to the true threat and intent of Allied operations, namely the preparation of three battery positions, NO's. 7, 9 and 10, opposite the Trinidad and Santa Maria Bastions and the French immediately began work on the 27th March to raise the counterguard of La Trinidad and the unfinished ravelin covering the front.

Inside the city, the French demolished houses and gardens and cut trenches across streets as they worked hard on a retrenchment behind the two bastions, however on the last day of March the Allied batteries were in position and two of them fitted out with twenty-six heavy guns opened fire on the right face of La Trinidad and the flank of the Santa Maria bastions, prompting the French gunners to reply sending at least 5,000 cannon balls into the Allied lines.

Colonel Jean Lamare, Phillipon's chief engineer described the effect of the guns;

"Before night there was a good deal of rubbish at the foot of the wall which working parties and sappers went to clear. Our brave troops always executed these operations with the greatest courage, remaining exposed for four or five hours to grape shot and the projectiles of every description which the enemy directed upon the point.

The town also suffered much; desolation was general amongst its inhabitants; the greatest number terror-struck sought refuge in the cellars, and in the churches, which they imagined to be bomb proof but where many were killed under their frail protection.

The garrison had no casements whatsoever, nor even the smallest shelter from blinds; nevertheless our loss in killed and wounded from 16 March to the present moment did not exceed 700 men."

The British guns blasted away through the 1st and 2nd of April, seeing a gradual slackening of French return fire as the parapets of both bastions were destroyed and the replacement parapets of wool bales and sandbags equally removed almost as soon as they were placed.

Lieutenant George Simmons, 95th Rifles was forward, looking to pick off any unwary gunners on the wall;

"I was with a party of men behind the advanced April sap, and had an opportunity of doing some mischief. Three or four heavy cannon that the enemy were working were doing frightful execution amongst our artillerymen in their advanced batteries. I selected several good shots and fired into the embrasures.

In half an hour I found the guns did not go off so frequently as before I commenced this practice, and soon after, gabions were stuffed into each embrasure to prevent our rifle balls from entering. They then withdrew them to fire, which was my signal for firing steadily at the embrasures. The gabions were replaced without firing the shot. I was so delighted with the good practice I was making against Johnny that I kept it up from daylight till dark with forty as prime fellows as ever pulled trigger.

These guns were literally silenced. A French officer (I suppose a marksman), who hid himself in some long grass, first placed his cocked hat some little distance from him for us to fire at. Several of his men handed him loaded muskets in order that he might fire more frequently. I was leaning half over the trench watching his movements. I observed his head, and being exceedingly anxious that the man who was going to fire should see him, I directed him to lay his rifle over my left shoulder as a more elevated rest for him.

He fired. Through my eagerness, I had entirely overlooked his pan, so that it was in close contact with my left ear; and a pretty example it made of it and the side of my head, which was singed and the ear cut and burnt.

The poor fellow was very sorry for the accident. We soon put the Frenchman out of that. He left his cocked hat, which remained until dark, so that we had either killed or wounded him.

My friends in camp joked me a good deal the next morning, observing, "Pray, what's the matter with your ear? How did the injury happen? " and so on.

Weather for some days good."

On the 3rd of April a third battery was brought to bear against La Trinidad, directing their fire against the breach so as to ricochet into the retrenchments behind and deter the French working parties from their duties.

French return fire reduced still further a the garrison sought to preserve its remaining stocks of ammunition and so resorted to using marksmen placed in covered ways, behind loopholes and positioned in rifle pits to try and pick off the enemy artillery men in the battery positions.

Colonel Lamare described the ongoing situation;

"Death was dealt in every direction amongst us, the ramparts were crumbling to pieces, the breaches becoming practicable, the efforts which the workmen made nightly to clear them, were ineffectual. In this state of things the Council of defence was assembled in order to make the last arrangements."

Writing on the 4th of April he continued;

"... we continued our preparations for sustaining the assault; the artillery had posted their men at the guns in the flanks of the bastions, loaded with grape shot.

At about ten o'clock in the morning a strong column of the enemy's infantry arrived by the Elvas road, on the left bank of the river, and formed on the Albuera road. We also observed a long train of waggons loaded with scaling ladders and all the preparations which announced the approaching assault."

|

| Position 6 on the Oman Map of the Allied Siege in 1812. |

Throughout the 5th April, thirty-eight heavy British guns hammered away at the La Trinidad and Santa Maria Bastions and by sunset the breaches were declared practicable.

As Wellington inspected the breaches, he was informed that Soult had reached Llerna the previous day (see the map of Estremadura at the top of the post) a situation that precluded Wellington taking more time to convince the garrison to surrender and reluctantly forcing him to prepare orders for an assault later that evening.

Lieutenant Grattan described the air of expectancy among the Allied troops;

"On this day the batteries of the enemy were nearly crippled, and their replies to our fire scarcely audible; the spirits of the soldiers, which no fatigue could damp, rose to a frightful height—I say frightful, because it was not of that sort which alone denoted exultation at the prospect of their achieving an exploit which was about to hold them up to the admiration of the world; there was a certain something in their bearing that told plainly that they had suffered fatigues, which they did not complain of, and had seen their comrades and officers slain while fighting beside them without repining, but that they smarted under the one, and felt acutely for the other; they smothered both, so long as their minds and bodies were employed; now, however, that they had a momentary license to think every fine feeling vanished, and plunder and revenge took their place.

Their labours, up to this period, although unremitting, and carried on with a cheerfulness that was astonishing, hardly promised the success which they looked for; and the change which the last twenty four hours had wrought in their favour, caused a material alteration in their demeanour; they hailed the present prospect as the mariner does the disappearance of a heavy cloud after a storm, which discovers to his view the clear horizon. In a word, the capture of Badajoz had long been their idol.

Many causes led to this wish on their part; the two previous unsuccessful sieges, and the failure of the attack against San Christoval in the latter; but, above all, the well-known hostility of its inhabitants to the British army, and perhaps might be added a desire for plunder, which the sacking of Rodrigo had given them a taste for. Badajoz was, therefore, denounced as a place to be made an example of; and, most unquestionably, no city, Jerusalem excepted, was ever more strictly visited to the letter than was this illfated town."

At four o'clock however orders arrived announcing that Wellington had countermanded his orders and the assault was postponed, this following a close inspection by the wounded chief engineer Colonel Fletcher who on seeing the French placed obstacles littering the breaches recommended a third breach be made to the curtain between the other two.

The news of the delay did not go without incident as the men in the assault divisions unsurprisingly aroused to their duties took out their disappointment on the engineers who were roundly and occasionally violently abused until cooler heads were able to restore order and convince all concerned in the wisdom of the decision.

|

| Position 6 on the Oman Map of the Allied Siege in 1812. |

With the news of Soult's advance, Wellington ordered Leith's 5th Division around the city to the south-west to occupy the Cerro del Viento, whilst relocating the bulk of the army to Albuera to be prepared to offer battle if necessary.

The following morning on the 6th April fourteen heavy howitzers opened fire from the right of the first parallel against the curtain wall between La Trinidad and the Santa Maria bastions, and by four o'clock, that afternoon, a practicable breach was declared.

The third breach heralded an all out bombardment by every Allied gun in the lines in an effort to further degrade the town's defences and prevent French efforts to shore up the damage, with orders issued for the place to be stormed at half past seven that evening.

However the three and half hours between the breach being caused and the time set for the assault proved to be not long enough for all preparations to be made and so the assault hour was moved back ten o'clock, allowing the French garrison an extension to shore up the defences as best they could.

Another error in Allied planning would be exposed when the assault was finally launched in that the scarp in front of the ditch before the three breaches had not been blown up in preparation, which would have normally caused a rubble slope down into the ditch for the attackers to descend before crossing and climbing up the rubble slopes of the breaches and rushing the defences en masse.

This omission in preparations would force the attack to stall as the assault infantry would be forced to jump down into the ditch, before forming up again to press their attack up and into the breaches causing them to spend longer under the guns of the defenders than would have been preferable.

In addition to Allied failures in their preparations, the French had added further to the problems the attackers would face by preparing a ditch behind the counterscarp, now deepened to sixteen feet in which the French had, unseen by the besiegers, flooded the area that would further impede the attempted rush of the attack whilst under the guns of the defences beyond.

|

| Position 7 on the Oman Map of the Allied Siege in 1812. The massive ditch that would have fronted the walls has given way to a city park |

In the breaches themselves the French had littered the debris slope with a multitude of obstacles equally designed to maim and impede the progress of the assault infantry; ranging from chevaux-de-frise, made from razor sharp cavalry sabre blades, planks studded with twelve inch spikes and chained to the ground, backed up by fascines and wool packs designed to replace fallen ramparts and grenades and barrels of powder ready to be rolled down the slope among the Allied troops.

|

| Position 7 on the Oman Map of the Allied Siege in 1812. The scars of the siege born on the walls of the Santa Maria bastion |

Each soldier manning the defences was to be armed with three muskets, laid along the parapet ready for immediate use and Lieutenant de Ruffey of the 58e Ligne arranged for a boat of soldiers to be moored in the flooded ditch at the salient angle of the La Trinidad bastion, able to enfilade any attackers attempting to get across it.

|

| Position 7 on the Oman Map of the Allied Siege in 1812. |

Finally, at the foot of the counterscarp, immediately in front of the breaches, sixty, fourteen inch shells had been laid in a circle, four yards apart and linked with 'mine tubes' of powder, designed to act as fuses, with the whole array covered in earth and under the control of Lieutenant Maillet of the Miners.

At ten o'clock on the 6th of April 1812 all was ready in Allied lines for the assault to commence and the divisions detailed for the attack were in position.

Wellington's plan of attack mirrored his approach used in the assault of Cuidad Rodrigo in January with multiple attacks around the perimeter in addition to those against the breaches designed to stretch the defences and take advantage of any weakness wherever that might occur.

General Picton's 3rd Division would move out right from the first parallel, cross the Rivellas and take the castle by escalade.

General Coleville's 4th Division would storm the breach at La Trinidad, whilst Barnard's Light Division would attack the breach at Santa Maria, whilst also providing 100 picked men to act as sharpshooters against the defenders on top of the bastion.

Each assaulting division would have an advance party of 500 men carrying twelve ladders, whilst the men of each forlorn hope would carry large sacks of grass to be thrown down into the ditches to break the fall of the men jumping down into them.

Further diversionary attacks were to be made by Leith's 5th Division on the Pardaleras fort and an escalade against the San Vincente bastion, whilst a detachment under Major Wilson of the 48th Foot would attack San Roque, whilst Power's brigade of Portuguese would make a feint attack against San Christobal.

The spirits of the troops were high, but all were well aware that the hours preceding the attack may well be their last;

Captain Kincaid of the 95th Rifles, reminisced;

"In proportion as the grand crisis approached, the anxiety of the soldiers increased; not on account of any doubt or dread as to the result, but for fear that the place should be surrendered without standing an assault; for, singular as it may appear, although there was a certainty of about one man out of every three being knocked down, there were, perhaps, not three men, in the three divisions, who would not rather have braved all the chances than receive it tamely from the hands of the enemy. So great was the rage for passports into eternity, in our battalion, on that occasion, that even the officers' servants insisted on taking their places in the ranks; and I was obliged to leave my baggage in charge of a man who had been wounded some days before."

Bugler William Green, confirms Kincaid's account;

"Our bugle major made us cast lots which two of us should go on this momentous errand; the lot fell on me and another lad. But one of our buglers who had been on the Forlorn Hope at Ciudad Rodrigo offered the bugle major two dollars to let him go in my stead.

On my being apprised of it, he came to me, and said 'West will go on the Forlorn Hope instead of you.' I said 'I shall go where my duty calls me.' He threatened to confine me to the guard tent. I went to the adjutant, and reported him; the adjutant sent for him, and said, 'So you are in the habit of taking bribes;' and told him he would take the stripes of his arm if he did the like again!

He then asked me if I wished to go? I said 'Yes sir.' He said 'Very good,' and dismissed me.

Those who composed this Forlorn Hope were free from duty that day, so I went to the river, and had a good bathe; I thought I would have a clean skin whether killed or wounded, for all who go on this errand expect one or the other."

At twenty minutes to ten, the silence was broken by the rattle of musket fire as Major Wilson's party attacked the San Roque lunette, moving against the rear of the small emplacement and placing scaling ladders against the ramparts.

|

| The 7th Fusiliers assault the defences of the small lunette of San Roque about twenty minutes before the main attack against the breaches began. |

Meeting little resistance the position was soon taken by the 300 man detachment, as recorded by Lieutenant Robert Knowles of the 7th Fusiliers who took part in the attack;

"When the 3rd Division advanced to commence their attack upon the castle we advanced to the Raveline, and after considerable difficulty we succeeded in placing one ladder against the wall, about twenty-four feet high.

|

| The Luis de Morales Museum, houses some excellent models depicting the siege of 1812 |

A corporal of mine was the first to mount it, and he was killed at the top of it. I was third or fourth, and when in the act of leaping off the wall into the Fort I was knocked down by a discharge from the enemy, the handle of my sabre broke into a hundred pieces, my hand disabled, and at the same time I received a very severe bruise on my side, and a slight wound , a piece of lead (having penetrated through my haversack, which was nearly filled with bread, meat, and a small stone brandy-bottle for use in the trenches during the night) lodged upon one side of my ribs, but without doing any serious injury.

I recovered myself as soon as possible, and by the time seven or eight of my brave fellows had got into the fort, I charged along the ramparts, killing or destroying all who opposed us.

I armed myself with the first Frenchman's firelock I met with, and carried it as well as I was able under my arm. The greater part of my party having joined me, we charged into the Fort, when they cried out 'prisoners'."

Knowles then sat himself down on a wall giving him a front seat view of the other attacks on the town and with the main assault about to begin.

|

| Model of the Breech in the Trinidad Bastions by Curro Agudo Mangas and displayed in the Luis de Morales Museum in Badajoz. |

"We were told to go as still as possible, and every word of command was given in a whisper. I had been engaged in the field about twenty-six times, and had never got a wound; we had about a mile to go to the place of attack, so off we went with palpitating hearts.

I never feared nor saw danger till this night. As I walked at the head of the column, the thought struck me very forcibly 'You will be in hell before daylight!' Such a feeling of horror I had never experienced before."

|

| Lieutenant de Ruffey of the 58e Ligne and his boat load of soldiers engage the assaulters from the flooded ditch |

Colonel Lamare wrote;

"A very dark night favoured their approach. The columns of attack arrived on the glacis without being seen; the heads of these columns instantly leaped into the ditches and arrived at the foot of the ruins.

The clinking of arms was heard; a sudden cry was raised - 'there they are! there they are!'

Sergeant John Spencer Cooper was with the 7th Fusiliers in the ditch when the French lit the fuse to the mines placed in their path;

"When our men had approached within three hundred yards of the ditch, up went a fire ball. This showed the crowded state of the ramparts,and the bright arms of our approaching columns. Those men who carried grass bags to fill up the ditch, and ladders for escalading the walls, were now hurried forward. Instantly the whole rampart was in a blaze; mortars, cannon, and muskets roared and rattled unceasingly. Mines ever and anon blew up with horrid noise. To add to this horrible din, there were the sounding of bugles, the rattling of drums, and the shouting of the combatants.

|

| The mine explodes in the breaches as the assault parties struggle forward in the flooded ditch |