In this second post covering Carolyn's and my visit to the British Museum in April 2024 to see their latest exhibition, Legion Life in the Roman Army, I pick up from Part One, which you can start with, if you missed it in the link below.

|

| JJ's Wargames - The British Museum - Legion Life in the Roman Army, Part One |

Legionary Defence

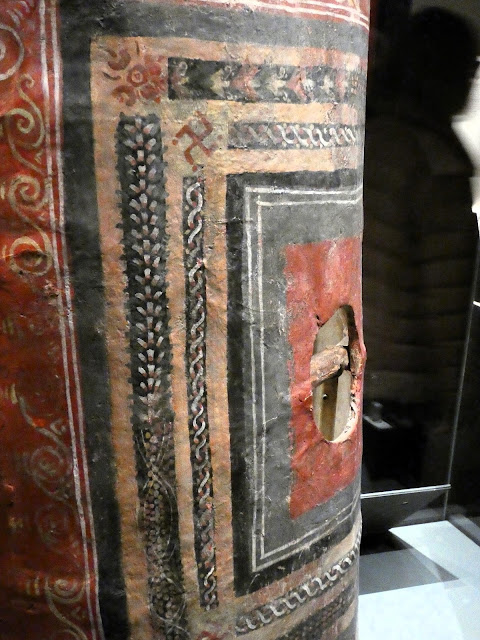

Despite the countless made, this is the only complete surviving Roman legionary long shield or scutum and is from Rome's Syrian frontier, where the dry climate preserved the wood and its remarkable painted leather surface.

Its cylindrical shape is now more curved than it would have been and it clearly displays Roman victory and legionary motifs, including an eagle with a laurel wreath, winged victories and a lion, adorning the military red background.

|

| Wood, leather and bronze: Dura-Europa, Syria, Early AD 200s |

|

| A scene from Trajan's Column showing the 'testudo' or tortoise manoeuvre, interlocking their scuta in a tank-like formation to advance against Dacian defences under enemy missiles whilst trampling fallen enemies underfoot and providing a ready made ramp for other brave souls to mount and attack the higher parts of the walls to their front. JJ's Wargames - Trajan's Column |

While Roman auxiliaries mostly used flat oval shields, this semi-cylindrical profile helped legionaries interlock shields in battle manoeuvres, as portrayed on Trajan's Column in Rome, but by the AD 250s, legionaries abandoned the shield type in favour of those used in the auxiliary cohorts.

Defend and Attack

The central boss, below, is from England and carries personifications of the four seasons decorating each corner, whilst a central eagle clutches an olive branch, flanked with military standards, the Roman god of war, Mars, and a bull. |

| Metal: River Tyne, England, Early AD 100s |

Editors Note: I have to say that these two items, the shield and boss, were my stars of the exhibition and a personal joy to have seen up close, especially the scutum, given its rarity and that it has survived in such an amazing state of preservation and is perhaps one of the most iconic items of equipment of the early to mid imperial Roman army.

Enduring Life under the Skins

Tents became the temporary homes of soldiers and emperors alike and their cost was taken from soldiers' pay, with one mother of a deceased soldier recorded as having received a twenty denarii refund for her son's one-eighth share of a tent.

|

| Test Panels: Leather, Vindolanda Fort, Northumberland, England, 100-200 AD |

|

| Tent Pegs: Wood, Vindolanda Fort, Northumberland, England 85-410 AD |

On the March

Terentianus was ordered from Egypt to the empire's eastern front, probably in 113 AD for emperor Trajan's campaign against Parthia, Rome's superpower rival.

|

| Sandstone, Corbridge, Northumberland, England, 138-61 AD |

Packed Up

Though mules and oxen transported larger camp items, soldiers were expected to carry personal equipment and armour even on marches over vast distances.

|

| Leather: Bar Hill Fort, East Dunbartonshire, Scotland, 142-80 AD |

The leather has been stretched at the centre by the shield boss, and this one covered an oval shield of the type used most by the auxiliary troops, rather than the rectangular legionary version.

A Military Monarch

Roman rulers could achieve military credibility with the rank and file by pitching up with their troops, and some empresses such as Julia Domina and empress Faustina II the wife of emperor Marcus Aurelius carried popularity among the soldiers that could lead to their recognition as mater castorum (mother of the camp) formalised by its further broadcasting on Roman coinage.

Mobile Field Hospitals and the Army Medic

Terentianus complained of being robbed of his bedding while in sick bay.

Medical provision helped to prevent depletion of the ranks, and a report from Vindolanda Fort notes 31 soldiers as sick and out of action on one particular day, a 4% reduction in fighting strength.

The archer commemorated on the tombstone below holds a bow and possibly an arrow shaping tool, and wears a sword belt and a shoulder quiver of arrows.

Setting up Camp

Turf ramparts and wooden stakes protected marching-camps overnight and soldiers carried two stakes with their kit, which also included an entrenching pickaxe.

|

| Soldiers dig ramparts to make a camp, under the direction of a centurion - Peter Connolly |

Unfortunate Terentianus relates that his pickaxe was stolen by an officer.

|

| Pickaxe: Iron with modern wood shaft, Hod Hill, Dorset England, 43-75 AD |

Troops had to work quickly, with camps often pitched after a long day's march and often under enemy threat, and upon departure everything was dismantled and levelled to prevent its use by the enemy.

|

| Stake: wood, Chesters Fort, Northumberland, England, 80-410 AD |

Armies often changed camps nightly, not least because they quickly became muddy and polluted with food, animal and human waste.

|

| Some camps of strategic importance eventually took on a look of more permanence as defences were improved on the original layout. |

Carting the Camp

An eight-man tent party had a pack mule for command supplies including a folded leather tent of about forty to forty-five pounds, two tent poles, pegs, ropes digging tools, a portable mill to grind grain, and extra food.

The bell seen above is from a draft mule found on a part of the suspected Teutoburg Forest battlefield, with its neck broken by a harness as it tumbled into a ditch. The bell had been stuffed with grass, dulling its chime to avoid alerting the enemy and may well have part of a Roman group attempting to escape the slaughter of the final battle by slipping away with the animal under the cover of darkness.

Septimius Severus, ruled 193-211 AD, was a Roman governor proclaimed emperor by his troops, and whilst securing his position through civil wars, won wider loyalty by increasing soldiers' pay, social status and marriage rights.

|

| Marble, Rome, Italy, 200-10 AD |

The marble bust above depicts him in imperial traveling gear of tunic and military officers cloak, he being an emperor who fought and travelled widely with his armies and dying in York while campaigning in Britain.

|

| Septimius Severus and Julia Domina with their sons, Caracalla and Geta (face defaced after his fall from power). The couple were Roman provincials of North Africa and Syrian descent respectively. |

Empress Julia Domina, depicted below, accompanied her husband, emperor Septimius Severus, on his extensive military campaigns, and this bust shows her distinctive hairstyle, curving up at the back and held with horizontal braids, seemingly to resemble a military helmet.

|

| Marble, probably Rome, Italy, 203-17 AD |

Roman units had permanent medics who provided medical care on campaign, with some being simply bandage-men, soldiers excused from chores to nurse comrades, whilst others were doctors who administered medicines and undertook battlefield surgery.

Medical instruments such as the bone saw, forceps and knife, seen below, were used with only opium as an anaesthetic, and there were no antiseptics. Some patients even survived so-called heroic surgery, inside the abdominal cavity.

|

| Medical Box: Copper alloy, Yortan, Turkey - Bone Saw: France - Knife: Italy 1-400 AD |

Army medics were on hand to deliver first aid during and after battle as well as treating ailments back at base.

|

| Stone: Housesteads Fort, Northumberland, England, 74-410 AD |

The tombstone above commemorates Anicius Ingenius, a 25-year-old military doctor stationed on Hadrian's Wall.

|

| Medics depicted on Trajan's Column |

Medical provision helped to prevent depletion of the ranks, and a report from Vindolanda Fort notes 31 soldiers as sick and out of action on one particular day, a 4% reduction in fighting strength.

Spreading Diseases

Soldiers living and working in close quarters spread diseases and the Antonine plague was a pandemic introduced to Rome by campaigning armies returning from the empire's eastern frontier in 166 AD.

|

| Marble: Alexandria, Egypt, 194 AD |

The marble inscription above was dedicated by forty-one legionary veterans enlisted in an accelerated recruitment drive after 168 AD, replacing casualties of the plague.

Archers

The 1st Hamian cohort of Syrian archers were stationed on Hadrian's Wall, and similar units are depicted on Trajan's Column in fantastical eastern garb, but in reality, most likely dressed like typical Roman infantrymen.

|

| Tombstone: Stone, Housesteads Fort, Northumberland, England, 100-200 AD |

|

| Quiver: Leather, Birdoswald Fort, Cumbria, England, 122-410 AD |

The leather cover seen above, from an archer's quiver is a rare survival.

Legionaries in Battle Formation

During battle inexperienced soldiers occupied the front line, blocked from retreat by the older men, a position young Terentianus might have found himself in when he still had the stamina of youth and ignorance of the horror of combat.

|

| Stone: Saint-Remy-de-Provence, France, 1-50 AD |

Tormenting the Enemy

Roman artillery (tormenta) catapulted bolts up to five-hundred yards, some with a cage of burning rags, while ballista hurled stone balls up to two-hundred yards.

Animal sinew was wrapped around their metal torsion frames and frame washers, seen below released tension when not in use to prevent the sinews from wearing out. The D-shaped blocks also in the picture below, are for a small catapult, from an armourers store and are unfinished and without the holes for the torsion frames.

|

| 2. Catapult Bolts, 3. Frame Washers, 4 D-Shaped Blocks |

|

| Closer look at the D-Shaped Blocks |

|

| Wood and Iron: Modern replica bolts |

The replica light-calibre catapult (scorpio) has the two D-shaped blocks similar to the unfinished (undrilled) original pieces found in the fort at Carlisle, seen above.

|

| Replica light-calibre catapult |

For extra elevation, catapults could be set up on high ground beyond the battlefield or even cart-mounted (carroballista) as mobile artillery.

.jpg) |

| From the Column of Trajan another carroballista, this one apparently in action. The soldier to the far left seems to be turning the winch while the soldier in the cart aims. |

Each century of eighty soldiers maintained a cart-mounted catapult, while the cohort of some 300 to 400 men shared larger war machines.

Mounted Archers

Mounted archers provided mobility and greater elevation to boost effective bowshot range.

Syrians such as Proclus were renowned within the Roman army for their archery skills, and Proclus was seconded from his position as a provincial auxiliary to the emperor's bodyguard, with his outsider (non-citizen) status useful to assure his political loyalty was more likely focussed on the emperor.

Emperor Hadrian

Hadrian ruled from 117-138 AD and is depicted here as a military commander, wearing an officer's cloak and cuirass.

|

| Marble, Tivoli, Italy, 125-30 AD |

In major battles, active military emperors were often just behind the lines, directing operations; although an experienced general, in 135 AD, the now elderly Hadrian was much further away, confined to Rome, and only able to learn how general Arrian, serving on the eastern frontier, defeated the cataphracts through written correspondence.

Terentianus was nearing retirement at this time and his legion was not involved.

|

| Lucius Flavius Arrianius (Arrian) the Greek historian, and Roman commander who fought the Alans - Peter Connolly |

Illustrated above, during Rome's 135 AD battle against the Alan cataphracts, the sky over the Roman shield wall is thick with pila, javelins, arrows and scorpio bolts.

Cataphracts

The cataphract cavalry depicted on Trajan's Column are fancifully portrayed in lightly fitting armoured suits for horse and rider.

In reality the horses were protected by an armoured blanket, such as the uniquely preserved example shown here.

|

| Iron, linen and leather, Dura-Europa, Syria, 200-300 AD |

This horse armour uses larger scale-like plates than that seen on human armour, and it was lost when Roman Dura-Europa was destroyed by the Sasanians under Shapur I in 256-57 AD.

By this time, cataphracts had also joined the Roman ranks, so it could have belonged to a rider from either side.

During battle the horse's head and neck were also armoured, with sieve-like metal guards resembling insect eyes shielding the beast's vulnerable eyes from projectiles; and a leather face mask (chamfron), similar to the one shown below, held the eye guards and afforded further protection.

|

| Mask: leather, Newstead Fort, Scottish Borders, Scotland, 80-100 AD Eye Guards and Decoration: Copper alloy, Ribchester, Lancashire, England, 75-150 AD |

Death on the Battlefield

In 197 AD, Septimius Severus and his rival Clodius Albinus clashed in civil war at Lyon, France, and the equipment seen below was found on the remains of a soldier from Severus' victorious army, hurriedly buried on the battlefield.

|

| Silver and copper alloy, Lyon, France, 197 AD |

His belt inscription 'use with good luck' was in vain.

Triumphal Symbols

Roman art is rich in the symbolic language of victory and emperors famously celebrated military success with triumphant processions through Rome, parading spoils and captives.

|

| The Arch of Titus at the principle entrance to the forum from the Colosseum. JJ's Wargames - Rome 2022, Return to the Eternal City |

The silver coin depicts triumphal ornaments, an eagle-tipped sceptre and laurel crown flank ornate robes, with the reverse showing a triumphal chariot.

On the terracotta relief, Roman soldiers lead distressed prisoners in chains.

A more permanent architectural commemoration is depicted on the gold coin seen below, with a depiction of the arch for emperor Claudius's victorious British invasion of 43 AD.

Rome's triumphal arches were originally topped with statues, and the coin shows emperor Claudius on horseback flanked by humanlike trophies or captured arms and armour. Only fragments of his arch survive in Rome.

The Spirit of the Standards

Imbued with spiritual significance, military standards were revered by the troops, with a shrine room created at the headquarters building in which were kept an altar to the spirits of the emperor and the standards kept alongside imperial portraits between campaigns.

|

| JJ's Wargames - Deva Victrix (Roman Chester Part One), Chester 2018 |

Empresses who accompanied the army, such as Julia Domna, are depicted sacrificing to the standards in their role as 'mother of the camp'.

|

| Stone, Rochester Fort, Northumberland, England, 238-41 AD |

The altar to the spirits of the emperor and the standards above, is from the shrine room at Rochester fort and dates from 238-41 AD.

Protective Amulets

Decorative personal adornments are common finds from forts and these small items that became detached or lost can offer insights into the beliefs of their wearers.

|

| Pendants: Jet, Colchester, England, 100-400 AD |

|

| Intaglios: glass, Vindolanda Fort, Northumberland, England, 85-410 AD |

The Bathhouse and Gaming

Forts had bathhouses, probably shared with the neighbouring civilian township, for relaxation and recreation as much as cleaning, and they were used not only by soldiers, but also their families.

|

| Impression of the fortress bath complex at Caerleon as it may have appeared in 80 AD - Paul Jenkins, National Museum of Wales, from our visit to the National Roman Museum in 2016. JJ's Wargames - Caerleon and the National Roman Legion Museum, Part One |

The thick wood-soled sandals kept bathers' feet dry and safe from burning on the heated floors of the bathhouse and the man sized clogs seen here were accompanied by smaller ones suitable for women and teenagers at Vindolanda Fort.

|

| Wood and leather, Vindolanda Fort, Northumberland, England, 85-410 AD |

Warm bathhouses were a favourite place for off-duty soldiers to relax and socialise, especially in the sometimes cold forts along the empire's northern frontier.

Coins, counters and food waste attest to gaming and gambling, accompanied by snacks including shellfish, meats, fruits and olives.

Needless to say, the dice tower seen below was a very special item for any wargamer to see and we honour our Roman forbears to this day by referring to 'rolling the bones' when referring to our die rolls and I regularly use dice towers for most of my games these days.

|

| Sandstone and glass, Vindolanda Fort, Northumberland, England, 85-410 AD |

Written Records and a Birthday Party Invite

Here we see a letter from Claudia Severa to Sulpicia Lepidina inviting her to her birthday party, with the greater part of it written by a scribe, but with the text below in Severa's hand, and representing the earliest woman's Latin handwriting known.

Written by the Scribe:

'Claudia Severa, to her Lepidina, greetings.

On the third day before the Ides of September (11th September), sister, for the day of the celebration of my birthday, I give you a warm invitation to make sure that you come to us, to make the day more enjoyable for me by your arrival, if you are present.

Give my greetings to your Cerialis. My Aelius and my little son send their greetings.'

|

| The part of the letter illustrated above, with Severa's own note, bottom right, as seen above. Text translated by Alan K. Bowman |

Written by Claudia Severa:

'I shall expect you sister.

Farewell, sister my dearest soul, as I hope to prosper, and hail.'

These thin wooden sheets with faded handwritten ink, represent the voices of people living and working at Vindolanda Fort 1,900 years ago, as illustrated above with Claudia Severa's invitation to her birthday party to the matriarch of Vindolanda, Sulpicia Lepidina who also discusses medicines with Paterna, a female apothecary in the letter below.

The administrative documents below mention food supplies held up in winter.

Below is an inventory from the commander's residence which includes necklace-locks, loincloths, headbands and colourful curtains.

This list of household goods is an inventory of items registered to the house of Flavius Cerialis, commander of the Batavians (a Germanic tribe), who lived with his family at Vindolanda Fort, and letters from his wife, Sulpicia Lepidina also survive.

Below is a close up of the page on the left, above, where the scribe has crossed out the last line.

An Officer's Wife

Records from Vindolanda Fort on Hadrian's Wall suggest that contagious eye ailments were a common problem in the cramped barracks.

The Vindolanda letters of Claudia Severa, remind us of the presence of noblewomen and children in forts, with her invitation to her friend Lepidina to her birthday party and on a trip to the nearby town of Corbridge, and talks of her little boy.

|

| Stone, Carlisle, Cumbria, England, 74-410 AD |

The tombstone above has lost its inscription, but the woman is depicted in a genteel pose, with an elegant fan, her young son playfully reaching for a pet bird on her lap; with this woman possibly an officer's wife, who lived in an official residence within the fort.

Abbas, an Enslaved Child

Below is a sale of contract between two marines for a seven-year-old Mesopotamian boy, Abbas (also given the Greek name Eutyches).

|

| Papyrus, Faiyum, Egypt, 166 AD |

Quintus Julius Priscus, a trumpeter who probably captured the boy on campaign, made the sale to Caius Fabullius Macer, a centurion's assistant, for 200 denarii (over a third of Macer's salary). Enslaved boys like Abbas could become a soldier's groom.

Prescriptions

As in camps, fort life involved close quarters living, so diseases could spread quickly.

Impressed into eye sticks of eye ointment, this stamp names two oculists (eye-doctors), Amandus and Valentinus, perhaps father and son, or brothers. Their wares include vinegar salve for running eyes, drops for dim sight, poppy salve and a mixture for clear eyes.

Personal Hygiene

The elaborate broach at the top of the display pictured below is also a travel toilet set with tweezers, ear scoop, and nail cleaners, to care for personal appearance and cleanliness on the move.

|

| Broach and Toilet Set: Copper alloy and enamel, England, 100-300 AD Combs: Wood, Vindolanda Fort, Northumberland, England, 85-410 AD |

Combs for head lice are commonly excavated from forts, particularly in soldiers' barracks, where close living spread lice, and they are often personalised with decoration or even names, as sharing was not a hygienic option. Roman doctors recommended close cropped hair during campaign to guard against infestation.

Eating and Drinking

There were no canteens in forts but, as in camp, soldiers cooked and ate meals communally in their section of eight men.

|

| A legionary makes good use of his trulla, sat by his fire in Germania |

A handled drinking cup (trulla) was essential gear, used like a ladle to dip into well buckets or streams.

|

| Copper alloy and enamel, Cup (replica): Original from Wiltshire, England, 130-40 AD Handle: findspot unknown, 43-410 AD |

This cup (at the front) is unusually ornate, showing a souvenir-like commemoration of Hadrian's Wall, with a rampart decoration above which are inscribed the names of five Wall forts: Bowness-on-Solway, Burgh-by-Sands, Stanwix, Castlesteads and Birdoswald. From a different cup, the handle is enamelled with once-colourful hares and hounds.

Supplying the Fort

Army outposts could demand huge amounts of supplies, and forts seemingly held one years' worth in stock for the hundreds of resident soldiers and their families.

|

| Barrel: Wood, Bar Hill Fort, East Dumbartonshire, Scotland, 142-60 AD |

|

| Seal: Lead, Carlisle, Cumbria, England, 96-410 AD |

Beware of the Guard Dog

The marble statue of a seated Molossian hound is a Roman copy of a bronze original from the Greek world.

|

| Marble, Probably Rome, 100-200 AD |

Regina the Freedwoman of Barates, alas!

The tombstone below with its heartfelt lament, belongs to Regina, a freeedwoman and wife of the soldier Barates.

|

| Stone, Arbeia Fort, Tyne and Wear, England, 100-200 AD |

Though she came from southern England and he from Palmyra in Syria, they lived and died (she aged 30) on Hadrian's Wall. A freedwoman wife suggests initial enslavement as Barates's concubine.

Inscribed in Latin with its lament in Palmyrene, it was possibly made by a Syrian sculptor at Arbeia Fort (which could mean 'place of the Arabs') Regina sits on a wicker chair, spinning thread from a basket of wool.

Fort Families

In forts, official families lived in centurions' quarters and the houses of higher-ranking officers. Unofficial families squeezed into cramped barracks, or else resided in adjacent townships.

|

| Leather, Vindolanda Fort, Northumberland, England, 85-410 AD |

The lace-up soldier's boot above was a practical choice in a northern climate. The woman's shoe below still has hobnails on the sole, marrying frontier practicality with style.

|

| Leather, Vindolanda Fort, Northumberland, England, 85-410 AD |

|

| Leather, Vindolanda Fort, Northumberland, England, 85-410 AD |

Women in Forts

Officer's wives, concubines, other enslaved women and girls, local women and even empresses visited, lived and worked in forts. Terentianus asked permission from home to buy a concubine, but we do not know if his request was approved.

|

| Human hair and jet: York, North Yorkshire, England 200-400 AD |

Evidence of women and girls within fort walls include personal ornaments such as earrings, and hairpins similar to those in this bun of hair, the only preserved remains of a woman buried in a lead-lined coffin filled with liquid plaster.

The pot next to the hair resembles Julia Domna, locally made merchandise probably commemorating her residence amidst the soldiers in York's fortress from 208-11 AD.

|

| Ceramic: York, North Yorkshire, England 200-25 AD |

Memorial to a Child

Representations of children, particularly young girls, are rare from the Roman world and the example below is a poignant memorial to Vacia, who died aged three, having spent her short life amongst the military community on Hadrian's Wall.

|

| Stone, Carlisle, Cumbria, England, 100-200 AD |

However an older child is depicted, perhaps suggesting that it was a ready made tombstone, and portrays a little girl dressed in a long belted tunic and cloak, and holding a bunch of grapes in her right hand.

Military Preparation begins Young

Troops in positions of power might exploit local populations or even their comrades, from moneylending and profiteering to scamming and swindling; with Terentianus a victim of theft by fellow soldiers and superiors.

The bones offer no clue to their cause of death, but the haphazard burial suggests an illicit and violent end for both men, tumbled one on top of the other without respect or dignity.

One motivation for soldiers who were granted citizenship after 25 years of service might be their son's improved prospects. Many sons of soldiers also entered the profession, some perhaps inspired by childhood experiences of army life. Some troops described their origins as castris, meaning they were born in camp.

|

| Wood, London, England 43-410 AD |

The small wooden sword above was likely a toy, used by children playing at soldiering.

Abusers and Abused

With limited numbers of soldiers policing a vast empire, military justice could be summary and often beatings were arbitrary with criminals and rebels alike routinely executed to discourage others.

Such underhand treatment fed resentment a resistance, military rosters list soldiers 'slain by bandits', however troops who broke the rules were not outside the law, sometimes suffering similar fates to the peoples they controlled.

Murdered Soldiers?

Two Roman soldiers, identified by their swords, military fittings and boot hobnails, were found hastily buried in Canterbury, England. One was a young adult, aged 20 to 34, the other was aged 35 to 49 when they died.

|

| Human bone, Canterbury, Kent, England, Late AD 100s |

Canterbury was a strategic point on the road from the English Channel to London and perhaps the two men were possibly cavalrymen, suggested by their long swords, acting as staionarii, policing this important transport route.

The diet of both men was that typical of Roman soldiers, including wheat, barley, root vegetables, meat and dairy. Radiocarbon dating and the style of the long swords suggests they served under the Antonine emperors, in the late AD 100s.

Crucified

One of the most extreme execution practices in the Roman world was crucifixion, and such a prolonged and painful death was reserved for the enslaved and free non-citizens.

|

| Human bone and iron, Fenstanton, Cambridgeshire, England, 100-200 AD |

Terentianus and other citizen-soldiers gave up their rights when they enlisted, making crucifixion for desertion or cowardice an ever-present threat.

In 60 or 61 AD, Boudica's revolt in southeast England followed a period of relative calm after the Roman conquest, but in the turmoil that followed, her Iceni people razed Colchester, then the capital of Roman Britain and a settlement for retired soldiers.

|

| Boudica raises her people in revolt to Roman rule - Peter Dennis/Osprey |

This helmet is made from pieces of Roman helmets found in the city's destruction debris, a reminder of the number of Roman soldiers killed in the attack.

|

| Iron, Colchester, Essex, England, about 60 or 61 AD |

Boudica was only defeated after London and St Albans had suffered similar fates.

The Teutoburg Disaster

A Roman citizen and cavalry commander of Germanic origin, Arminius treacherously teamed up with his native tribes in 9 AD, to successfully ambush three legions led by Publius Quinctilius Varus, the Roman governor of Germania, and Varus and his entire army were destroyed.Arminius evaded Roman retribution, ridding his homeland of Roman rule, but was ultimately murdered by opponents within his own tribe.

Below is the world's most complete Roman legionary's articulated cuirass, found on the battlefield.

Analysis suggests the soldier died wearing it.

|

| Iron, Kalkriese, Germany, 9 AD |

|

| Iron, Kalkriese, Germany, 9 AD |

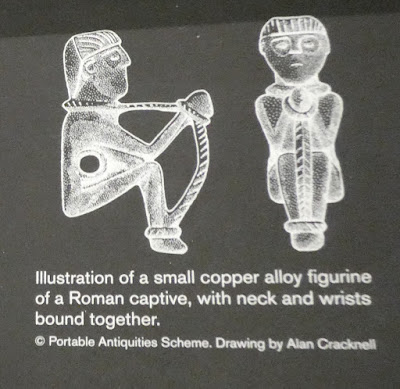

The wider end fitted around the captive's neck and the opposite end cuffed the wrists, probably tightly and painfully, in a fixed position, offering no means of escape and could be worn forwards or backwards for greater discomfort.

For perhaps fifty percent of soldiers fortunate enough to have survived illness and violence, the rewards of honourable discharge and social transformation awaited at the end of twenty-five years of service.

Citizen-soldiers like Terentianus received a lucrative bonus upon retirement, whilst for auxiliaries, it was a fundamental change of status, with Roman citizenship affording them rights and privileges in law, taxes and property.

Such a soldier might traverse and defend a vast empire, but only through completion of service could he, and by extension his family, truly count as a citizen of Rome.

|

| Emperor Caracalla in a bid for political popularity alongside his military pay rise extended universal citizenship to all unenslaved inhabitants of the Roman World. Marble, Rome, Italy, 215-7 AD |

Eventually, social upgrades came before retirement. Emperor Septimius Severus, 193-211 AD, improved pay and rights for soldiers. His son Caracalla, 198-217 AD, extended universal citizenship to all unenslaved inhabitants of the Roman World.

This radical change ended the difference between legionaries and auxiliaries, and transformed the Roman empire.

Last Will and Testament

Below is part of a legal tract on edicts concerning the inheritance rights of the heirs of Roman soldiers given by emperor Hadrian.

|

| Papyrus fragment of Ulpian's Ad edictum, book 45, Batn el-Hant (ancient Theadelpheia), Egypt, 213-50 AD |

Soldiers become Gentlemen

In his pursuit of military popularity, emperor Semptimius Severus introduced new rewards and marital rights for Roman soldiers, with pay multiplied and ordinary troops permitted the trappings of Roman gentlemen such as fine cloths and gold jewellery.

|

| Gold, Rome, Italy, 193-211 AD |

Set with a gold coin of Severus, the man sized ring above is a show of wealth as well as loyalty.

|

| Gold, River Rhine between Kostheim and Kastel, Germany, 150-250 AD |

|

| Gold, Cologne, Germany, 150-250 AD |

|

| An optio keeps order in the rear ranks in his usual position on the left flank, supporting his centurion in the centre front rank. |

A Soldier leaves this World

Estimates suggest half of Roman soldiers died in service before reaching retirement, probably as much due to natural causes as battle.

|

| Marble, Alexandria, Egypt, 160-90 AD |

The inscription notes: '. . . he went on to another world that is no world, where there is nothing else except darkness.'

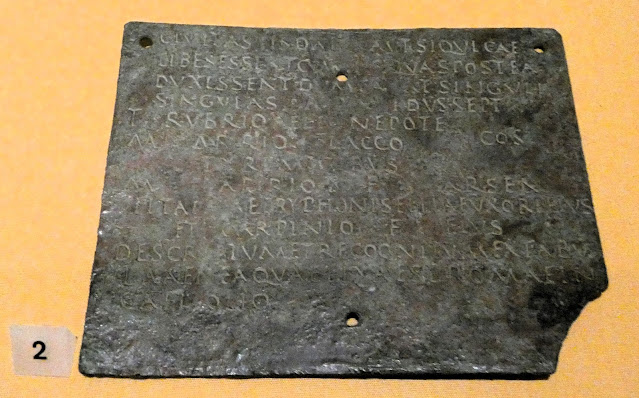

This diploma was awarded to auxiliary cavalryman Gemellus from Pannonia (Hungary), following 25 years' service and it extended citizenship to one wife only, to deter polygamy, and their children.

His retirement was conferred in Britain during Hadrian's visit in 122 AD, perhaps in the presence of the emperor himself.

Marcus Syrus, Citizen of Rome

Life Savings

Soldiers were encouraged to bank savings, not least to discourage desertion, since such an act meant abandoning hard-earned pay, and even without the end-of-service cash reward bestowed upon legionaries, auxiliary soldiers could save up in preparation for their retirement.

|

| Papyrus, Al-Bahnasa (ancient Oxyrhynchus), Egypt, 100-200 AD |

The papyrus above records the purchase of prime land reserved for Roman citizens in Egypt by an auxiliary veteran named Marcus Julius Valerianus, in a transaction enabled by his new citizen status.

Honourable Retirement

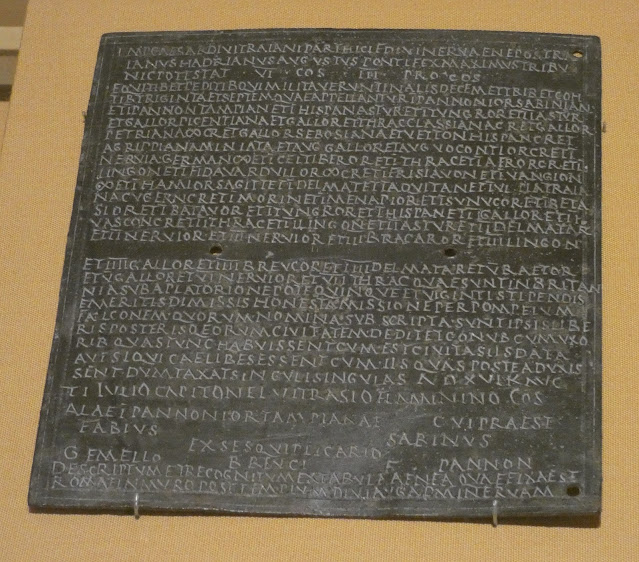

Most Roman soldiers were required to serve twenty-five years, and when retirement finally arrived, the cherished reward of citizenship was bestowed in the form of a double-leaved tablet (diploma), signed by seven witnesses and sealed.

|

| Bronze, Egypt, 8th September 79 AD |

This diploma confirms the formal discharge from the Egyptian-based fleet of a rower, Marcus Papirius, after 26 years' service, marines and their shipmates served and extra year, but even lowly galley-rowers were afforded the status and rewards of soldiers, and Papirius's wife Tapaea and their son Carpinius became citizens too.

Cherished Citizenship

Citizenship gave retired soldiers the full rights and privileges of Romans throughout the empire, with respect to laws, taxation, property and governance.

|

| Bronze, O-Szony, Hungary, 17th July 122 AD |

A letter of introduction for purchasing land, Terentianus, who entered the service as a lowly marine before progressing to become a soldier of the legion is described as a 'man of means', and as a citizen-soldier he was entitled at retirement to a cash reward equivalent to ten years' pay, some 120 gold coins (aurei).

The hoard below comprises 126 aurei, approximately ten and half years wages.

|

| Gold and ceramic, Didcot, Oxfordshire, England, 180-9 AD |

Marcus Syrus, originally from Jerash, Jordan, retired in 71 AD after serving 26 years as a marine at Misenum, Italy, and was granted citizenship after honourable discharge by emperor Vespasian.

|

| A first century Roman marine |

This diploma was recovered from Syrus' workshop-residence in Pompeii, kept safe in his bedside alcove.

|

| Bronze, Pompeii, Italy, 71 AD |

Without the benefit of a cash reward, he evidently retired into a civilian trade, living and working in Italy, half a world away from Jerash, a Roman citizen transformed by his military service.

This concludes my review of 'Legion Life in the Roman Army' presented by the British Museum in 2024, a wonderful presentation of some of the best artefacts in the world and certainly providing me with plenty of inspiration when the time comes to resume work on my own collection of figures from this period.

If you are interested in seeing more posts looking at Roman history from the JJ's Wargames back catalogue, I've attached a few links above and you can interrogate the tabs at the top of the blog entitled Early Imperial Rome and JJ's Dacian Wars.

I'm off on my travels this weekend with a 'Boys Beano to Newark' to see the Partizan Show on Sunday, so will hope to post some pictures and thoughts about the show on my return. Until then.

More anon

JJ

.jpg)

A great write-up and beautifully presented as always JJ. Seeing Trajan's column has always been a highlight for me, as was visiting the legionary museum in Caerleon. The British museum exhibition and the chance to see that Roman shield first-hand would rank up there for me.

ReplyDeleteI'm off to see this in a couple of weeks... I'm working in Euston for a morning so it seemed the perfect opportunity to pop in.

ReplyDeleteHi Chaps,

ReplyDeleteI'm just back from a weekend up in Newark with friends visiting Partizan 2024, and saw your comments.

Firstly thanks for your remarks, and I would reiterate what an extraordinary exhibition this is and would encourage anyone with the opportunity to go and see such an amazing collection of Roman items geared very much towards the military aspects of the Roman empire which I reckon anyone reading this blog might have a slight interest in, and Alastair, enjoy, you're in for a treat.

Cheers guys

JJ

Well done a fantastic post.

ReplyDeleteWillz.

Hi Willz,

DeleteThanks mate, glad you enjoyed it.

JJ