In my last post we were heading back out on the road after a wonderful two-day stop over in Húsavík that included a bit of whale watching and were now heading west on the final leg of our twenty day road-trip around Iceland, and there is a link below to the previous post and those that preceded it below.

|

| JJ's on Tour, Iceland, Land of Fire & Ice Part Three |

As the map of our route below reveals, we were now on a rather long leg of our trip to Blönduós, Point 11, via the capital of north Iceland, Akureyi accessing the town through the 4.6 mile long Vaðlaheiðargöng road tunnel.

.jpg) |

| https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Va%C3%B0lahei%C3%B0arg%C3%B6ng_(2019).jpg |

|

| The "Capital of North Iceland", Akureyri, pictured as we descended from the Vaðlaheiðargöng road tunnel. |

Given the road conditions would likely cause our journey to take about three hours to our next stop over we decided to stop in Akureyi to get a few groceries and a pay quick visit to the town botanical gardens.

Open all year round, the Akureyri Botanical Garden is unique and significant in that it is one of the northernmost botanical gardens in the world, just 53 miles south of the Arctic Circle.

The garden has its origins in 1910 when women from Akureyri founded the Park Association with the goal of beautifying their city. The city had granted them a hectare of land the previous year, making the Akureyri Botanical Garden the first public park in Iceland.

The garden also contains several wooden houses, including Eyrarlandsstofa, one of the oldest houses in Akureyri, adding to the historical and cultural significance of the site.

Hosting a diverse range of plant species, with around 400 species of Icelandic plants featured in its southeastern corner, by the end of 2007, the garden boasted approximately 7,000 species, including plants from arctic regions as well as those from temperate zones and high mountain areas.

Returning to the car and filling up with fuel in preparation for our long drive, we headed off across some remarkable terrain, and that's saying something for Iceland, demanding occasional stops in suitable pull in places to get some pictures along the way.

We were now heading into the land of the Sagas populated by folks such as Eiríkr Þorvaldsson better known as Erik the Red, Valthjof, and Valthjof's friend, Eyjolf the Foul, not to mention Hrafn the Dueller, but more about them later.

As we descended into the lower lying valleys, the conditions improved as did the visibility, and an opportunity to take a closer look at a creature very distinctively Icelandic.

|

| The Icelandic horse, not just another type of pony. |

Developed from ponies brought to Iceland by Norse settlers in the 9th and 10th centuries, the breed is mentioned in various documents from throughout Icelandic history and centuries of selective breeding have developed the Icelandic horse into its modern physical form, together with natural selection having also played a role in overall hardiness and disease resistance; the harsh Icelandic climate likely eliminated many weaker horses early on due to exposure and malnourishment, with the strongest passing on their genes.

In 982 AD the Icelandic Althing (parliament) passed laws prohibiting the importation of horses into Iceland, thus ending crossbreeding. The breed has now been bred pure in Iceland for more than 1,000 years.

As the daylight started to draw in, a feature we noted was starting earlier with each day seeing us lose an hour of daylight in the morning and evening by the end of our tour, we arrived at Brekkukot Cottages, our accommodation, just eight miles south of Blönduós, and we got ourselves settled in for the night with me making best use of the groceries bought in Akureyi by cooking dinner.

|

| Glaumbær Farm & Heritage Museum. https://www.glaumbaer.is/is/en |

|

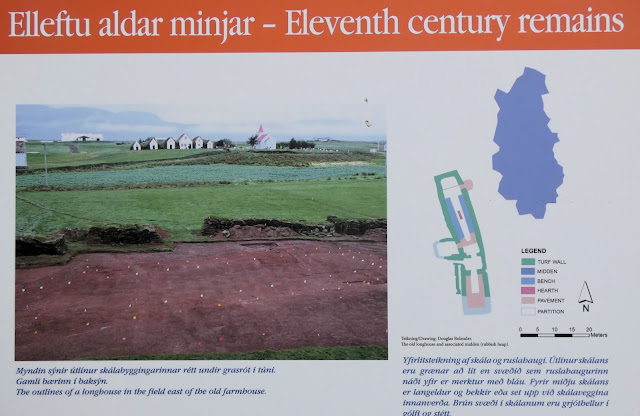

| The levelled field beyond the sign on the raised farm mound revealed a 90 foot long longhouse following remote sensing and excavation of the site. |

The yellow building is Áshús, while the gray one is Gilsstofa.

Áshús was built at Ás at Hegranes, Skagafjörður in 1884-86, and was moved to the Glaumbær Museum site in 1991.

|

| Áshús was built at Ás at Hegranes, Skagafjörður in 1884-86 |

The house, in its new location near to the old turf farmhouse, represents the type of buildings that supplanted turf houses in the 19th century, and also serves as a reminder of the hard lives lived by Icelandic rural people, telling the story of an influential home that played an important role in improving agricultural methods and techniques in the region in the period around 1900.

|

| Gilsstofa built circa 1849 |

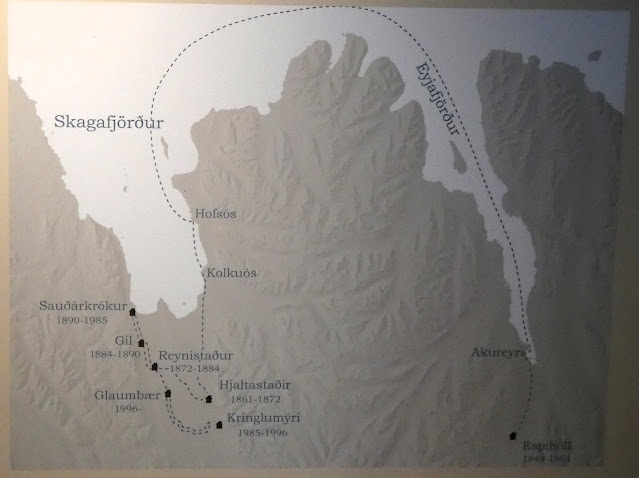

The first leg of the journey was over the ice from Espihóll to Akureyri, where the timber was loaded onto a ship which transported it to Skagafjörður. From there the timber was then towed to Hjaltastaðir, where the regional administrator lived until 1872.

The house was dismantled once more, and the timber was dragged over the frozen waters of Héraðsvötn to Reynistaður, where it remained until 1884. From 1873 to 1892, the building housed the Skagafjörður regional administration, and was also used as a location for social gatherings. It served as a theatre for the first local drama productions, and a variety of entertainments were held there.

In 1884, a new regional administrator took over. He lived at Gil, not far from Reynistaður, the house was moved there, where it remained until 1891, when it was transferred to Sauðárkrókur. In its sixth incarnation, it was assigned a new function. It was now known as Gilsstofa (the house from Gil).

A farmhouse is said to have stood on the hill at Glaumbær since the Age of the Settlements (900 AD). The present buildings, seen below vary in age; the most recent addition having been built in 1876-79, while the oldest – the kitchen, "long pantry," and middle baðstofa – are believed to have been preserved much as they were in the mid-18th century. The passages connecting the individual units have also remained unchanged for many centuries.

The form of the farmhouse as it is today is similar to that of many large farmhouses in Skagafjördur from the 18th and 19th centuries, and between 1879 and 1939, the farmhouse at Glaumbær remained unchanged; it was repaired and declared a conserved site in 1947, the year the last inhabitants moved out. An English benefactor, Sir Mark Watson, contributed a gift of £200 for the renovation of the farmhouse, which was crucial to its preservation. |

| 'Gilsstofa has an interesting history as it was repeatedly moved from place to place in the years from 1862 to 1891.' |

The house was dismantled once more, and the timber was dragged over the frozen waters of Héraðsvötn to Reynistaður, where it remained until 1884. From 1873 to 1892, the building housed the Skagafjörður regional administration, and was also used as a location for social gatherings. It served as a theatre for the first local drama productions, and a variety of entertainments were held there.

In 1985 it was taken on yet another journey by road to a farm, finishing up almost where it began its tour of Skagafjörður in the mid-19th century.

Gilsstofa was reconstructed at the Glaumbær museum in 1996-97.

|

| Glaumbær Old Turf Farm |

The Glaumbær estate provided little rock suitable for building purposes, but it has plenty of good turf, so the walls of the farmhouse contain relatively little rock; it was used only at the base of the walls to prevent damp from rising up into them. Imported timber and driftwood were used in the interior frame and panelling.

The farmhouse consists of a total of 13 buildings (houses), each of which had its own function.

This collection of buildings and the farm in particular were quite unlike anything to be seen back home and I would guess pretty unique to Iceland, but I have to admit as I made my way into the front hall and passage way into the farmhouse living space seeing the dried turf walls gradually replaced by carefully constructed timber panels, and snug living spaces, I found myself recounting Tolkien's description of Bilbo's hobbit hole and I'm sure he would have found great inspiration from a building like this;

Having soaked up the social history of Skagafjörður it was soon time to be back on the road, especially when the first coach party of tourists turned up, piling into the toilets prior to exploring the buildings we had just looked at.

|

| Eiríkr Þorvaldsson better known as Erik the Red, for obvious reasons as the depiction illustrates. |

We were now heading to Búðardalur, or more precisely Eiríksstaðir in Haukadalur (Hawksdale), a place I was much looking forward to seeing, it being the former homestead of no less an historical personage, Eiríkr Þorvaldsson better known as Erik the Red, and father of Leif Eiríksson, or Leif the Lucky, the first known European discoverer of the Americas.

|

| On the 586 grit road, illustrated on the map below, that runs alongside Haukadalsvatn, the two mile long lake that runs through Haukadalur on our way to the Eiríksstaðir Open Air Museum. |

|

| Eiríksstaðir can be seen at the centre of this map of the local area and we stayed at Stóra-Vatnshorn farm, shown close by. |

Indeed our accommodation for the night would be practically next door to his original tenth century homestead and the reconstruction of it that had been built close by.

|

| Icelandic voyages of exploration in the 10th and 11th centuries |

Medieval Icelandic tradition relates that Erik and his wife Þjódhild had four children: a daughter, Freydís, and three sons, the explorer Leif Erikson, Thorvald and Thorstein.

Unlike his son Leif and Leif's wife, who became Christians, Erik remained a follower of Norse paganism, and while Erik's wife took heartily to Christianity, even commissioning Greenland's first church, Erik greatly disliked it and stuck to his Norse gods—which, the sagas relate, led Þjódhild to withhold intercourse from her husband, and that probably didn't help his anger management issues and his habit of leaving lots of people dead who he fell out with.

As the sagas relate, similar to his father before him, Erik also found himself exiled for a time, with the initial confrontation occurring when Erik's thralls (slaves) caused a landslide on a neighbouring farm belonging to a man named Valthjof, and Valthjof's friend, Eyjolf the Foul, (what a great name!) killed the thralls.

In retaliation, Erik killed Eyjolf as well as Hrafn the Dueller (Holmgang-Hrafn), and then kinsmen of Eyjolf sought legal prosecution and Erik was later banished from Haukadalur for killing Eyjolf the Foul around the year 982.

|

| An example of ornamented pillars in the Saga Museum, Reykjavik. JJ's on Tour, Iceland, Land of Fire and Ice |

When Erik had finished building his new home, he went back to retrieve his pillars and timbers from Thorgest; however, Thorgest refused to return them to Erik, and so Erik then went to Breidabolstadr and took the pillars back. As a result, Thorgest and his men gave chase, and in the ensuing fight Erik slew both of Thorgest's sons as well as "some other men".

|

| Leif Erikson as portrayed in the Saga Museum, Reykjavik. JJ's on Tour, Iceland, Land of Fire and Ice |

Erik later died in an epidemic that killed many of the colonists in the winter after his son's departure.

I love, as I think many of us do in the hobby, exploring history through the land, the buildings, and relics that link back to the characters that walk the stage of events in the past, and often the tabletops we create, and nothing quite links you up with people from the dimmer more distant parts of history than being able to see replica buildings based on reconstructed originals; and I had a similar experience to this visit as when Carolyn and I visited Butser Ancient Farm back in 2018, link below.

|

| JJ's Wargames - Butser Ancient Farm and Experimental Archaeology |

However this particular visit took the experience to another level with the day drawing in and our guide dressed in period costume taking Carolyn and I and another couple into this marvellous reconstruction of what the original house, literally situated tens of yards away from where we were sat around a mock, gas fire surrounded with the day to day items and furnishings that would have likely be seen in that same building back in 982 when Erik prepared to leave Haukadalur for good.

|

| The adventure back to the tenth century begins! |

As we made ourselves comfortable around the gas fire in the centre of the lodge, it being explained that the beds we were sat on were designed for three occupants at a time, with all occupants sat upright when sleeping so as not to have their heads horizontal and thus in direct level with the fire that would have been kept alight during the long cold nights.

The hazard they wished to avoid by sleeping upright was to them an unknown cause, but related to dying in the night from carbon monoxide poisoning due to the build up of the gas from and around the fire in a turf lodge only ventilated by an opening in the roof directly above it.

The weaponry, the cloth weaving, the food and day to day life in a home like this during Erik's time were described in wonderful detail, that had me recalling our visit to York, or Viking 'Jorvik' in 2017, where many of the items shown and discussed were instantly familiar.

|

| The drift wood rafters covered in turf complete the roof with a square skylight opening over the hearth the only ventilation within. |

Following the identification of this site and initial excavations, in 2000 a pit-house was excavated next to the main building. Among other finds in the floor were carved stone spindles of Norwegian manufacture, which have been interpreted as having been a dyngja, a "bower" or women's work-room, having previously been viewed as a bath-house or sauna and a kitchen or smokery.

The "bower" or women's work-room can be seen in the pictures below.

|

Entrance to the "bower" or women's work-room. |

The building was simple in construction and indications are that it had not been occupied for long, with carbon 14 dating of charcoal from an undisturbed area of human habitation deposits in front of the ruins yielding a date of the 9th–10th century.

The museum was created in 1999 and formally opened in 2000 in association with the celebration of the thousand-year anniversary of the discovery of Vinland and is close to the actual ruins, which are a protected archaeological site.

With our visit over ending yet another busy day and dinner calling we made the short drive back up the valley to our lodgings at Stóra-Vatnshorn farm, and Carolyn took a few more pictures the next morning of this wonderful valley and the memories created with our visit that previous evening.

That next morning the lake was so still creating these perfect mirror conditions that Carolyn captured with the camera, before we were back in the car heading for the Snaefellsnes peninsula, Point 13 before our return to Reykjavik in preparation for catching a flight home.

|

| Back on the road and heading for our next destination, the Snaefellsnes peninsula. |

In the next post I'll pick up the final leg of our journey as we take a look at the magical West of Iceland before heading south to Reykjavik.

More anon

JJ

No comments:

Post a Comment