This year Carolyn and I decided to head off somewhere a bit different from a usual break in the sun and opted for a cooler place to visit, certainly temperature wise, but additionally a part of the world we were both keen to see for its extraordinary landscape, history and Nordic culture, which is also pretty cool.

So we caught an Iceland Air flight from London Heathrow to Keflavik International Airport the former Meeks Field US airfield opened on the 23rd March 1943 in WWII and now the main airport for Iceland just outside of the capital Reykjavik.

Before embarking on our travels, we like to do a bit of homework on our intended destinations and with several months of research and YouTube watching we were fairly familiar with key landmarks to expect to see as Iceland hove into view from our aircraft after a very quick flight of about two and half hours instead of the usual three hours plus.

|

| The Mýrdalsjökull ice cap atop the Katla volcano, visible from our plane as we begin to descend towards Keflavik. |

|

| Katla volcano erupting through Mýrdalsjökull ice cap in 1918 |

As we began our final approach into Keflavik the rugged nature of the terrain became even more pronounced at low altitude, that and the almost complete lack of any type greenery such as a tree, let alone woodland or forestry, and quite unlike anywhere else we had visited previously.

The still volcanically active Iceland rises out of the Atlantic Ocean, along the Mid-Atlantic ridge that separates the European continent from North America and is the result of a series of massive eruptions that occurred some fifteen million years ago that thrust the land up and above sea level.

|

| Our route plan around Iceland, starting and ending in Reykjavik the capital, following the ring-road on Route 1 with a few detours here and there. |

|

| The view from our apartment in Reykjavik, with the Hallgrímskirkja (Church of Hallgrímur) dominating the centre of town |

Given the time of year and the approach of winter likely to make its impact felt as we began to head into the northern parts of the country, we hired a four-by-four Dacia SUV to help deal with winter road conditions, but with no intentions of heading off into snowy wastes which in October mainly applies to the interior, and its gravel/dirt roads, often closed to wheeled traffic for obvious reasons.

This remarkable building was the creation of State Architect Guðjón Samúelsson's commissioned in 1937, and he is said to have designed it to resemble the trap rocks, mountains and glaciers of Iceland's landscape, in particular its columnar basalt "organ pipe" formations (such as those at Svartifoss).

With the church close to our accommodation it was one of the first places visited, and the views from the tower out over the city was a magnificent way to orient oneself to our new surroundings.

As well as taking an educated observation of the take off run of the aircraft seen climbing out from Reykjavik local airport below, it was also an opportunity to observe 'Sky Lagoon' the new ocean side geothermal lagoon and steam baths, just outside the city and seen in the background of the picture; looking like a Hobbiton inspired bunker on its grassy embankment but an experience to luxuriate in naturally hot thermal waters that abounds in Iceland, as well as enjoying a spa treatment and sauna looking out over the nearby harbour approaches.

|

| Beyond Reykjavik airport is the grass covered Sky Lagoon Spa and thermal baths which Carolyn and I enjoyed during our stay in Reykjavik. https://www.skylagoon.com/ |

The front of the church is dominated by the imposing statue of Leif Erikson or Leif the Lucky, a Norse explorer who is thought to have been the first European to set foot on continental America, approximately half a millennium before Christopher Columbus.

|

'Leif Erikson Discovers America' by Hans Dahl |

According to the sagas of Icelanders, he established a Norse settlement at Vinland, which is usually interpreted as being coastal North America, and there is ongoing speculation that the settlement made by Leif and his crew corresponds to the remains of a Norse settlement found in Newfoundland, Canada, called L'Anse aux Meadows, which was occupied approximately 1,000 years ago.

It is a common misunderstanding that Sun Voyager steel sculpture created by artist Jón Gunnar Arnason is a Viking ship, quite understandable given that Iceland is the land of the Sagas. However this was not the original intention, rather it is a dream boat and an ode to the sun, representing the promise of undiscovered territory and a dream of hope, progress and freedom.

Reading the nearby notice board explaining the importance of this relic of the old town I caught site of the picture below from about 1926 showing what the area would have looked like prior to WWII and with the little low-roofed house front of Garðhús at the centre of the photo.

This little house is remarkable for several reasons, one being that it is an example of a half-stone house that were built in the 19th century to replace the traditional turf dwellings in many coastal communities, namely turf walls were replaced with long walls of cut stone, and this rare example was built in 1884 by a local fisherman.

The 1976 agreement at the end of the Third Cod War forced the UK to abandon the "open seas" international fisheries policy it had previously promoted, seeing the British Parliament passing the Fishery Limits Act 1976, declaring a similar 200-nautical-mile zone around its own shores, a practice later codified into the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which provided similar rights to every sovereign nation.

|

| The statue of Leif Erikson was presented to the people of Iceland from the people of America on his supposed one-thousandth anniversary in 1937. |

|

| The Harpa Concert Hall and Conference Centre completed in 2011 at a cost of 164 million Euros, another remarkable building inspired by the basalt landscape of Iceland. |

It is a common misunderstanding that Sun Voyager steel sculpture created by artist Jón Gunnar Arnason is a Viking ship, quite understandable given that Iceland is the land of the Sagas. However this was not the original intention, rather it is a dream boat and an ode to the sun, representing the promise of undiscovered territory and a dream of hope, progress and freedom.

When I'm in a new town, I'm always looking for evidence of the 'old town' and a connection to its past and this particular little Icelandic cottage close to the portside as we made our way to the Saga Museum caught my attention, as did the historic boats beyond it.

|

| Garðhús the little house pictured above and seen here at the centre of a photo from 1926. |

This little house is remarkable for several reasons, one being that it is an example of a half-stone house that were built in the 19th century to replace the traditional turf dwellings in many coastal communities, namely turf walls were replaced with long walls of cut stone, and this rare example was built in 1884 by a local fisherman.

That fisherman, Bjarni Oddsson, granddaughter Þuríður Dýrfinna Þorbjarnardóttir, was born in Garðhús on 30 October 1891 and like her grandfather would prove to be an intelligent young women of strong character who would graduate from the Women's College of Reykjavik in 1912, as an unusually gifted linguist.

Her abilities saw her working at the Hotel Skjaldbreið in Reykjavík, dealing with foreign visitors, among whom was the Marquis Henri Charles Raoul de Grimaldi d‘Antibes et de Cagne, a member of one of Europe‘s oldest princely dynasties, of which the Monaco royal family is a branch.

Þuríður and Henri fell in love, and were married in Reykjavík in October 1921. The wedding received extensive press coverage, as it was rare for people of such noble birth to visit Iceland – let alone marry an Icelander.

In the second year of her marriage Þuríður fell ill with tuberculosis, and she travelled widely in search of a cure, including Belgium, where she died on the 10th October 1925, aged only 33, and she was buried in Brussels, where her grave bears the arms of the Grimaldis.

|

| The former trawler Gullborg was built in Denmark in 1946 and is now an exhibit outside the Reykjavik Maritime Museum |

Just beyond Garðhús my eye was drawn to the Gullborg trawler and the Reykjavik Maritime Museum, but I have to say it soon was caught by the sight of a vessel that was only too familiar to a young 'JJ' growing up in the late 70's and reminiscences of nightly news reports about UK involvement in the so called 'Cod War' with Iceland; that saw regular TV clips of Icelandic gunboats sounding sirens and cutting in between British Leander class frigates, such as HMS Scylla, and trawlers attempting, to get in close over the trawlers nets and gear with a cutting device towed behind, thus severing the trawl and preventing the catch from being brought aboard.

My memories are from the third of three such maritime disputes over fishing rights and boundaries for territorial waters between the two NATO countries and allies which would be decided in Iceland's favour at the cost of 2,500 British fisherman's jobs in an already hard pressed industry as well as £1-million of repair costs to damaged Royal Navy frigates.

|

| Coast Guard Vessel Óðinn's specially reinforced bow for sailing through ice. |

|

| Method of operation of the Icelandic Coast Guard's trawling net cutter. |

Thankfully these disputes are a thing of the past and the UK and Iceland share a tradition in the enjoyment of fish and chips, something that Carolyn and I were only too happy to help celebrate during our stay.

|

| Óðinn took part in the three Cod Wars where the most effective and famous weapon was the trawl warp cutter, which is displayed on the afterdeck. |

Continuing our exploration of Reykjavik, I was on the look out for any signs of bird life in the city that indicated where we were in the world, and I didn't have to wait long as we made our way through the city park and my eye was immediately caught by the swans bracing themselves against the sharp wind as the Mallard ducks kept themselves very much tucked up against the cold.

|

| The whooper swan "hooper swan"; Cygnus cygnus |

The more usual swan to see in the UK is the mute swan, Cygnus olor, with its familiar black bulb atop its bright scarlet bill, and so I immediately recognised this very large swan, almost goose like in appearance, as a whooper swan, which are here in this part of Iceland all year round but only seen in the more northern parts of the UK when wintering and until now I had only seen them as illustrations in my bird book.

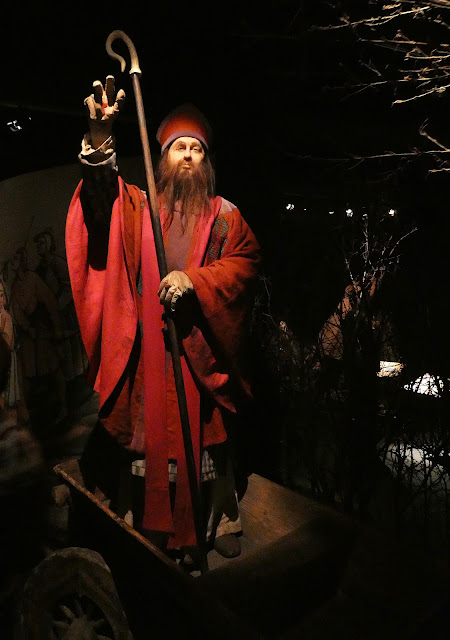

One of the final places I was keen to see during our stay in Reykjavik before packing our bags to head off along the ring-road was the Saga Museum with exhibitions of wonderful life size manakins beautifully sculpted and costumed.

|

| Saga Museum |

In a series of seventeen displays, the epic legends from the Icelandic sagas, with historical figures like Snorri Sturlusson, Ingolfur Arnarson and Leifur Eiriksson, and tragic episodes in the history of Iceland such as the disastrous Black death, the most devastating pandemics in human history, which claimed anything between 75 to 200 million people are brought to life in vivid detail.

|

| My rendition of Erik Oaksplitter and friends JJ's Wargames - Erik Oaksplitter and Companions |

I have to say that I was as interested as much for the history and drama the SAGA displays capture, as for the wonderful inspiration these figures provide for my next additions to my Dark Age collection, and the stories related to these depictions in the museum were to add extra colour and drama to the places that related to them that we visited later during our odyssey around Iceland.

The Papar

The people that we know to have lived in Iceland were the Papar, an Icelandic pronunciation from the Latin papa, via Old Irish, meaning "father" or "pope", who were Irish monks who are thought to have sailed to Iceland in simple curraghs (open skin covered boats) and took eremitic or solitary residence in parts of Iceland as hermits before that island's habitation by the Norsemen of Scandinavia, and their existence is attested by the early Icelandic sagas and recent archaeological findings.

They left behind them Irish books as well as crooks and bells from which it is possible to determine their origin.” This is the only mention by Ari the Learned of the Christian inhabitants of Iceland, but it ought to be pointed out that he was writing some 250 years after Iceland was settled by the Norsemen and therefore had little more than word-of-mouth reports and Dicuíl’s account to support his claims.

Hrafna-Flóki Vilgerðarson

The Vikings were known to be excellent sailors and navigators able to cross open ocean and discover new lands before returning home to tell others of their discoveries.

The first such explorer known to have come to Iceland was a Viking called Naddoður, of which the chronicles record how he sailed off course on his way back to Norway from the Faroe Islands and therefore found Iceland by complete chance.

Floki it seems decided not to rely on just observing any bird but instead took three ravens aboard with him for which he asked the blessings of the gods. En route he released the ravens in the hope that they would help him find the way to Iceland. The first raven flew towards the Faroe Islands, the second flew up into the air and then back down to the ship but the third flew forwards and thereby led Flóki to the coast of Iceland. From that time on he was therefore known as Hrafna-Flóki or Raven-Flóki.

Ingólfur Arnarson, with his wife Hallveig Fróðadóttir (c. 849 – c. 910) is commonly recognized as the first permanent Norse settler of Iceland and who arrived in the country in 874 AD.

After having thrown them into the water, Ingólfur came ashore at what was subsequently known as Ingólfshöfði, where he raised a house and spent his first winter.

Skalla-Grímur and Egill

One of the most celebrated blacksmiths of the Settlement Age in Iceland was the craftsman Skalla-Grímur Kveldúlfsson who can be seen here working alongside his son Egill.Grímur Kveldúlfsson is described as having been of a dark and unattractive complexion, reticent and little given to the company of others, losing most of his hair in his mid-twenties and was from that time on known as Skalla-Grímur or Grímur the Bald. He and his father, Kveldúlfur, were forced to leave Norway by King Harold Finehair and escaped to Iceland.

Kveldúlfur died before they reached Iceland, and it was his dying wish that his coffin be tossed into the sea, requesting his son to settle at whatever place the coffin washed ashore. Upon arrival Skalla-Grímur built the farmstead known as Borg at that spot near to the site of the present town of Borgarnes.

Skalla-Grímur was a great craftsman and set up a smithy down by the shore. There was a plentiful supply of iron ore but Skalla-Grímur had to dive into the water offshore to find a rock large enough to serve as an anvil. So heavy was the stone that it would have taken several men to carry up to the smithy to use as an anvil, but Skalla-Grímur had such great strength that he retrieved it alone from the bottom of the sea.

One of Skalla-Grímur’s sons inherited his dark complexion and foreboding features as well as his immense physical strength. He was called Egill and is considered to have been one of the outstanding poets of the Saga age.

The latest research on the genealogical connections between the Icelanders and the Irish on the one hand and the rest of Scandinavia on the other indicates that about eighty percent of the male population in Iceland at that time was of Nordic origin. However, the same research has shown that the greater part of the female population at the time was Celtic rather than Norse.

It is clear that a great many of the women were of Celtic origin, captured and enslaved by the Vikings who then took them to Iceland. One such woman was the famous Melkorka Mýrkjartansdóttir, one of the main characters in The Saga of the Laxdalers.

When Höskuldur returned home to Iceland, he took her with him, and despite Jórunn's irritation, the concubine was accepted into Höskuldr's household, though he remained faithful to Jórunn while in Iceland. The following winter the concubine gave birth to a son, to whom they gave the name Ólafr.

One day Höskuldr discovered Ólafr's mother speaking to her son; she was not, in fact, mute, and when he confronted her she told him that she was an Irish princess named Melkorka carried off in a viking raid when she was only fifteen, and that her father was an Irish king named "Myrkjartan" (Muirchertach) who has been associated with Muirchertach mac Néill.

Leifur the Lucky - Vinland

The expansion of Norse culture in the west and its search for new countries to settle or raid did not end with the discovery of Iceland, and it has been a common mistake for popular history to occasionally credit Erik as being the first European to discover Greenland, however, the Icelandic sagas suggest that earlier Norsemen discovered and attempted to settle it before him.

|

| 'Höskuldr discovered Ólafr's mother speaking to her son.' |

Leifur the Lucky - Vinland

The expansion of Norse culture in the west and its search for new countries to settle or raid did not end with the discovery of Iceland, and it has been a common mistake for popular history to occasionally credit Erik as being the first European to discover Greenland, however, the Icelandic sagas suggest that earlier Norsemen discovered and attempted to settle it before him.

|

| Summer in the Greenland coast circa year 1000 - by Carl Rasmussen |

Tradition credits Gunnbjörn Ulfsson (also known as Gunnbjörn Ulf-Krakuson) with the first sighting of the land-mass, as he made his way by ship from Norway to Iceland but ran ashore on an island west of Iceland. Eric the Red heard of Gunnbjörn’s troublesome journey and set sail from Iceland to be the first Nordic settler in Greenland.

According to the Saga of Eric the Red, Leif discovered Vinland after being blown off course on his way from Norway to Greenland. Before this voyage, Leif had spent time at the court of Norwegian King Olaf Tryggvesson, where he had converted to Christianity. When Leif encountered the storm that forced him off course, he had been on his way to introduce Christianity to the Greenlanders.

After they had arrived at an unknown shore, the crew disembarked and explored the area. They found wild grapes, self-sown wheat, and maple trees, and later they loaded their ship with samples of these newly-found goods and sailed east to Greenland, rescuing a group of shipwrecked sailors along the way. For this act, and for converting Norse Greenland to Christianity, Leif earned the nickname "Leif the Lucky".

Eric the Red also had a daughter Freydis, half sister to Lief Erikson and in the Saga of the Greenlanders, she is seen as evil and treacherous while The Saga of Eric the Red portrays her as outstandingly courageous in her fight against the natives of Vinland.

"Why run you away from such worthless creatures, stout men that ye are, when, as seems to me likely, you might slaughter them like so many cattle? Let me but have a weapon, I know I could fight better than any of you."

Ignored, Freydís picked up the sword of the fallen Thorbrand Snorrisson and engaged the attacking natives, and surrounded by enemies, she undid her garment and beat the sword upon her breast. At this the natives retreated to their boats and fled. Þorfinnr and the other survivors praised her zeal.

The Althingi

Towards the end of the settlement period the Icelandic chieftains decided to base their legal system on foreign prototypes. To this end a man named Úlfljótur, a farmer in the east who had many years of legal experience, was sent to Norway to learn all he could of the legal system there. The suggestions that he returned with were endorsed by the Icelanders but there was no writing tradition in the country at the time so the leaders of the legislature therefore undertook the extraordinary task of learning all the laws by heart.

|

| Lake Ölfusvatn, later named Þingvellir and the lake Þingvallavatn, the site of the first Althing in 930 AD. This was one of the first places we visited after leaving Reykjavik. |

The greater majority of the settlers of Iceland were heathen and believed in the old gods or Æsir as they were called.

Thorgier Ljosvetningagodi - Conversion to Christianity

In the year 1000 AD King Ólafur Tryggvason of Norway had taken four sons of Icelandic chieftains captive and sent two men, Gissur the White and Hjalti Skeggjason, to the country to deliver an ultimatum, that they would be killed if the country did not submit to Christianity. The king’s command was heard at the Althing that summer and was greeted with little enthusiasm by those who followed the old gods, and the Althing soon found itself divided into two distinct factions, those that favoured Christianity and those that were of the pagan persuasion, both rejecting the ways, beliefs and systems of law of the other and leaving the country on the brink of civil war.

Each faction was led by its own Law Speaker with the Christians electing Síðu-Hallur, whilst the pagans were led by Thorgeir Ljosvetningagodi Thorkelsson.

Thorgeir, himself a pagan priest and chieftain (a gothi), realised that a compromise between the two factions was required to avoid conflict and decided in favour of Christianity after a day and a night of silent meditation under a fur blanket, and under the compromise, pagans could still practice their religion in private and several of the old customs were retained.

The Icelandic church was established by the country’s leading chieftains and they chose one of their number to act as bishop. Many of these chieftains had churches built on their lands and became priests, sometimes even bishops so, to begin with, spiritual and worldly power was held by the same parties just as it was before the advent of Christianity.

Guðmundur was ordained as priest in 1185 at the age of 24, and a decade later, he had become one of the most influential clergymen in Iceland, culminating in his election as bishop of Hólar (the northern one of the two Icelandic bishop seats) in 1203.

|

Guðmundur Arason, 12th-13th century Icelandic bishop. Drawing is from a manuscript of Prestssaga Guðmundar góða |

The struggle for power between the elites and the church was characteristic of most European states at this time and Iceland was no different with Guðmundur, becoming a focal point in that struggle in his disputes with Icelandic chieftains, which faded over time, leaving his piety and generosity as a lasting legacy with the people that would see him seen as a national saint even though his place in Icelandic tradition has not been acknowledged by the Roman Catholic Church.

Grettir the Strong

Grettis saga is considered one of the Sagas of Icelanders (Íslendingasögur), which were written down in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries and record stories of events that supposedly took place between the ninth and the eleventh centuries in Iceland.During the commonwealth age in Iceland, 930 to 1262 AD, those found guilty of certain crimes were sentenced to be killed with impunity, and men could also sentenced to a three year exile and have a specific safe path, the straying from which meant certain death.

Grettir was a famous Icelandic outlaw whose story takes place some time between 980 to 1040 and he was outlawed for the first time at age fourteen and was forced to live outside of society for three years.

He would grow to become a strong and able man, if somewhat ill-tempered, and he would later go on to be outlawed again, with no time limit, and find himself hunted by the kinsmen of the people he had killed or wronged, becoming the longest surviving outlaw in Icelandic history, after nineteen years on the run, when his family asked for his banishment to be lifted.

|

| Grettir, all burly and ready to fight - Árni Magnússon Institute in Iceland |

It was ruled that he would have to survive the full twenty years and thus his enemies made one last effort to get their man and in relentless pursuit, with some magic thrown in for good measure, that caused Gettir to accidently wound himself; and thus unable to run, he was tracked down to the island of Drangey, off the northern tip of Iceland where he had sought to hide himself until his festering wound had healed.

Whilst fighting off his attackers with his brother Illugi he was killed.

Snorri Sturluson - A Poet and Politician

Snorri Sturluson, 1179 – 22 September 1241, was an Icelandic historian, poet, and politician.

The Black Death

Towards the middle of the fourteenth century, a deadly epidemic raged through Europe. It has variously been called the Great Plague or the Black Death and it wiped out about a third of the population of Europe. The epidemic originated in Asia and was divided into two strains, one carried by humans and the other by rats. The latter, and more common of the two, was the bubonic plague, distinguished by a swelling of the glands, high fever and severe head pains. The former and more deadly strain infected the respiratory system and was airborne. Its primary symptoms were extreme breathing difficulties and severe coughing.

The bubonic plague was mainly carried by rats and since there were hardly any rats in Iceland prior to the 18th century, it probably did not take root here. The Black Death did however not reach Iceland until about 50 years after its outbreak on the mainland.

The Battle at Orlygsstadir - 21st August 1238

The Battle of Örlygsstaðir was a historic battle fought by members of the Sturlungar family against the Ásbirningar and the Haukdælir clans in northern Iceland, and was part of the civil war that was taking place in Iceland at the time between various powerful clans during the time known as the Age of the Sturlungs.

The Battle of Örlygsstaðir was a historic battle fought by members of the Sturlungar family against the Ásbirningar and the Haukdælir clans in northern Iceland, and was part of the civil war that was taking place in Iceland at the time between various powerful clans during the time known as the Age of the Sturlungs.

The combined forces of Gissur and Kolbeinn had an easy and swift victory. About fifty of the Sturlungar men were killed and only seven from Gissur’s party while Kolbeinn’s force did not suffer a single casualty.

During the battle Sighvatur, then in his seventies, tried to hide himself behind a wall and when he was discovered by Kolbeinn’s men, they were ordered to slay him. Sighvatur received seventeen wounds and was stripped of his weapons and clothes.

In 1343 Sister Katrín, a nun at the convent of Kirkjubær in the south of Iceland was found guilty of having sold her soul to the devil and was punished by being burned at the stake. However, the annals from that period give differing accounts of the matter and her culpability appears to increase the further away from the scene of the event they were written. For example, in one account she is said to have given herself to a demon in a letter, and in another to have slandered the pope. In a third account, the letter to the demon is mentioned but she is also accused of having repeatedly committed fornication with men from outside the convent.

His son Sturla, a renowned warrior, fought on bravely, attacking the enemy with his famous spear Grásíða, but the shaft was so weak that he had to realign it with the spearhead after almost every stroke. He finally stopped fighting after receiving two deep wounds to the face and a third that pierced so heavily into his throat that the account says that one could have put three fingers into it.

When Sturla surrendered and pleaded for mercy, Gissur’s men granted it and covered him with a protective wall of shields. Then Gissur himself arrived, ordered his men to remove the shields and said: “I shall strike here” and delivered Sturla such a blow that he himself was “lifted up and saw the space between his feet and the ground.”

That blow proved not only to be the demise of Sturla Sighvatsson but also the end of the reign of the Sturlungar family.

Sister Katrin - The First Icelandic Martyr

Nevertheless, the first person to be convicted of heresy and suffer the awful fate of being burned at the stake was a nun called Katrín, nearly three centuries before the inquisition on the continent began.

Witch hunting became a popular sport in Europe and indeed into North America from the medieval era through to the so-called enlightenment era of the seventeenth century and Iceland joined in the merry contempt for human life with its batch of judicial killings of mainly strong willed independent women.

Iceland though was definitely later to the enlightenment values, pursuing the sport into the middle of the seventeenth century particularly in the area of the Western Fjords, but at least were an early adopter of the values of equal opportunity by including the prosecuting and burning of men at the stake along with women.

It should be noted in her defence that the pope in question was Clement VI and he was well known for his lechery and love of entertainment.

The voices for reform within the structure of the church grew louder, culminating in 1517 with the protest of the German monk and theologian Martin Luther who publicly denounced the church in Rome. From that time the Reformation was set in motion and its chief advocates turned out to be monarchs and various other secular leaders who saw an opportunity to fill their own coffers with the riches they could appropriate from the Roman church. Lutheranism was officially announced to be Iceland’s new religion at the Althing in 1541, but the Northerners and their bishop Jón Arason did not turn up to the assembly.

Bishop Jón became involved in a dispute with his sovereign, King Christian III, because of the bishop's refusal to promote Lutheranism on the island. Although initially he took a defensive rather than an offensive position on the matter, this changed radically in 1548, and at that point he and Bishop Ögmundur joined their forces to attack the Lutherans.

Hailing from the UK and having enjoyed a thorough education in the delightful period known as the English Reformation, I can easily relate to the turmoil suffered in Iceland by various parties when considering the various monuments to English martyrs dotted about County Towns in England such as Oxford and my own home town of Exeter.

The Icelandic church did not really begin to be a wealthy institution until the fifteenth century, when many farmsteads stood empty as a result of the plague or various natural disasters. Then they became available for a pittance and many of them were purchased by bishoprics. The manner in which the church thus amassed wealth was in full accordance with what was taking place in the rest of Europe.

In 1550, Jón and his two sons, Ari, and Björn, were finally captured and beheaded, ending his campaign for a Catholic Iceland. Christian Skriver, the king's bailiff who pronounced the bishop's death sentence, was later killed by fishermen who favored Jón's cause and the executioner was a petty criminal called Jón Ólafsson, who must have been tired by the time he came to his third victim because it took seven blows to ultimately severe the bishop’s head from his body. A year after these executions the Northerners avenged them by chasing down the executioner and pouring molten lead into his mouth.

Death Sentences and Execution in Iceland

From the latter half of the thirteenth century until the Reformation in the sixteenth century, offenders were tried under the Law Book Jónsbók, a formal codification of the laws, written in 1281 by Jón Einarsson, which demanded a sentence of death for crimes such as murder, thievery, rape and high treason.

In 1550, the Danish king was given judicial power in Iceland, and the amount of death sentences increased, with new laws added to the codex that meant that incest and cheating were now punishable with death, and by the seventeenth century secret pregnancies and child murders had also been added.

Between 1550 and 1830, 248 Icelanders were sentenced to death and during the latter half of the seventeenth century the principle group of offenders to increase were thieves or vagrants hanged for thievery, likely caused by the complaints from the upper-classes about the increase in beggars and homeless people after hard winters, with an Icelandic saying that a white flower known as 'Thieves Root' grows on the spot where a thief had been hung.

Imprisonment became a more frequent legal punishment at the start of the eighteenth century which presented Iceland with a problem as it had no prisons and so during the years 1730 to 1836, 165 (148 men and 17 women) Icelanders were imprisoned overseas, principally in Copenhagen.

Many Icelandic convicts were sentenced to Brimarhólmur, the main Danish shipyard as convict labourers.

Skarphéðinn Njálssonwas a semi-legendary Icelander who may have lived in the tenth century, and is known as a character in Njáls saga, a medieval Icelandic saga which describes a process of blood feuds, the saga believed to have been composed in Iceland during the period from 1270 to 1290.

|

| From Njáls saga: Skarphéðinn kills Thrain Sigfusson on the ice. |

Skarphéðinn is described as hardy and skilled warrior but also as an ill-tempered and sharp tongued man whose insults of potential allies at the althing ends up isolating Njáll and his family, leading to their demise as they are burned by their enemies inside their home at Bergþórshvoll.

I have to say that as a casual observer of the Icelandic Sagas I found the museum highly informative and well recommended for those of us interested in the history of Iceland embarking on a tour of the island like myself, as I found myself referring to the stories portrayed here as we journeyed to the different places on our tour.

In a follow up post or posts I will look at the highlights of our trip to Iceland as we head out from Reykjavik on Route 1 to get a closer look at the Land of Ice and Fire.

More Anon

JJ

Splendid! Thanks for the information from the Saga museum. Looking forward to part two.

ReplyDeleteHi and thank you, glad you are enjoying the read.

DeleteJJ