Corunna Retreat - Peninsular War Tour 2019

Battles and Actions in the Tagus Valley(Alcantara and Almaraz Bridges) - Peninsular War Tour 2019

Battles and Actions in the Tagus Valley, Battle of Talavera - Peninsular War Tour 2019

Badajoz, The French Siege and Allied First, Second and Third Sieges - Peninsular War Tour 2019

Cavalry Actions in Estremadura - Peninsular War Tour 2019

Elvas and the Battle of Albuera - Peninsular War Tour 2019

Battle of Bailen - Peninsular War Tour 2019

Our drive from Bailen to our house on the south coast, near La Manga, took us through yet more spectacular country, passing north of the Sierra Nevada,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tabernas_Desert

in the country that is home to the Spaghetti Westerns of my youth, and causing a moment of hilarity when, cresting a road climb, the countryside opened up to a vista straight out of 'A Fist Full of Dollars' and the Ipod immediately selected at random an Ennio Morricone number.

Following our long trip from the north coast via all the stop-offs along the way, both Carolyn and I were really looking forward to no driving and simply enjoying doing not a lot, but come the end of the week I was really looking forward to getting back on the road and plotting our course north around Madrid, via the Somosierra Pass.

Time pressure to get up to Burgos prevented any lingering on yet another famous Napoleonic battle site, and it like a few others it will have to wait for another time.

With Santander our final destination to catch the ferry home, we had allowed the late afternoon and most of the next day to explore Burgos and Vitoria, covering the campaigns of 1812 and 1813 before the French were finally forced to retire over the Pyrenees.

|

| Oman's map illustrating the area of the Vitoria campaign and the places we visited, highlighted on our journey to catch our ferry from Santander. |

Oman's map above shows the proximity of the two sites in relation to the coast, with the River Ebro dominating this part of Spain and the key towns and other rivers that came to feature in the campaigns of late 1812 and 1813.

A few years ago, I was very busy putting together my collection of figures recreating the Army of Estremadura as it was at the Battle of Talavera,with several posts looking at the history of the units in that army prior to their coming together for that particular battle.

That work led me to look at the units caught up in latter French invasion of 1808, led by the Emperor, that saw the Spanish armies, lining the River Ebro, rolled back in a lighting campaign by the Grande Armee.

|

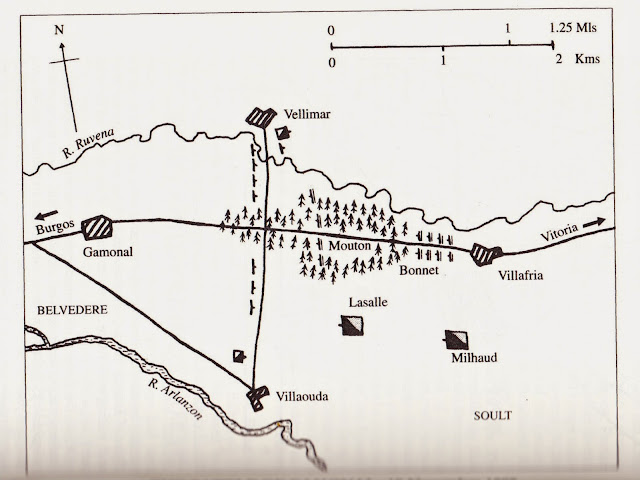

| Battle of Gamonal 10th November 1808 as mentioned in my post back in February 2015, looking at the Army of Estremadura and the units that came to compose it. https://jjwargames.blogspot.com/2015/02/the-army-of-estremadura-at-talavera-1809.html |

The Battle of Gamonal was one such battle in that campaign, that saw the woefully outnumbered army (10,349 Spanish vs 24,000 French) under the command of Mariscal de Campo Conde Belvedere caught by Marshal Soult before the walls of Burgos; with General Lasalle showing his flair as a cavalry commander by dismantling a Spanish line, almost single-handedly, as his brigade descended on the Spanish right flank just as the French infantry closed in on its front.

The battle saw the Spanish suffer 3,000 casualties, losing 16 guns and 12 colours.

|

| The Battlefield of Gamonal 2019, just outside of a much larger Burgos |

Any thoughts of considering the terrain in this battle during our visit were quickly dashed by the picture above showing that the hamlet of Gamonal has been swallowed up in the expansion of Burgos in the last two centuries and although the names of Villayuda and Vellimar still appear on sign posts on the road to Vitoria, the site of Lasalle's impressive cavalry attack is now a trading estate, that I have visited!

|

| My interpretation of 'The Volunteers of Badajoz' for Talavera 208 who also fought at Gamonal in 1808 https://jjwargames.blogspot.com/2015/02/1st-battalion-badajoz-volunteer-line.html |

So with the battle of Gamonal ruled out from our itinerary we headed towards the centre of Burgos to find our historic hotel before heading off into town to discover the other reason for coming, namely the famous castle atop the hill that overlooks it and which played a major role in the events of the autumn of 1812, following the battle of Salamanca, covered way back in July in the second post in this series.

Our hotel for our short stay was the 16th century late Gothic style Jesuit college, come military hospital, come army engineers college, the Palacio de Burgos, with its amazing cloister set at its heart and only a short walk away from the centre of town and up to the castle.

|

| Point 1 - The entrance to our hotel, the Palacio de Burgos to the right of the bell tower |

|

| The beautifully maintained cloister is from another age |

|

| Now converted into a modern function room, perfect for weddings and conferences |

Dropping our bags off and having had a freshen up in our room following the drive up, we immediately headed off into town following the banks of the River Arlanzon, set amid weeping willows, and with the spires of the nearby cathedral peeking over the riverside buildings, making the place look like Cambridge, except a lot warmer.

|

| The crowning spires of Burgos Cathedral above the River Arlanzon |

|

| The River Arlanzon, practically a brook at this time of year, mid summer |

After a short walk we came to the bridge leading across to the magnificent 14th century, Arco de Santa Maria medieval gate house in front of the square beyond and the 13th century Cathedral of St Mary of Burgos, whose spires dominate the view.

|

| Point 2 - Looking towards the Arco de Santa Maria gatehouse across the bridge |

Burgos on the River Arlanzon, is the historic city of Castile, and perhaps its most famous son would be El Cid Campeador, the medieval Castilian knight circa 1043 to 1099 who played a key role in the wars against the Moors.

The site of Burgos was thought to have been a Celtic settlement when the Romans arrived and following Augustus's reorganisation of its new province in 27 BC it became part of Hispania Tarraconensis, with the last people to be pacified by Rome situated in the area and along the northern coast.

Following occupations of the region by the Visigoths and Berbers, it was King Alphonso III the Great of Leon who conquered the region in the middle of the 9th century building several castles for Christendom to secure his newly won territory, giving the region its name Castile or 'land of castles'.

In 884 the city of Burgos was founded and under Count Fernan Gonzalez established an independence within Castile, subject to its kings, eventually establishing it as the favourite seat of the kings of Leon and the capital of the Kingdom of Castile.

Napoleon passed by in 1808 following the French victory at Gamonal as described by Oman;

'The Castle of Burgos lies on an isolated hill which rises straight out of the streets of the north-western corner of that ancient city, and overtops them by 200 feet or rather more.

Ere ever there were kings in Castile, it had been the residence of Fernan Gonzalez, and the early counts who recovered the land from the Moors. Rebuilt a dozen times in the Middle Ages, and long a favourite palace of the Castilian kings, it had been ruined by a great fire in 1736, and since then had not been inhabited. There only remained an empty shell, of which the most important part was the great Donjon which had defied the flames.

|

| San Roman church seen at the foot of castle hill, Burgos |

The summit of the hill is only 250 yards long: the eastern section of it was occupied by the Donjon, the western by a large church, Santa Maria la Blanca: between them were more or less ruined buildings, which had suffered from the conflagration.

Passing by Burgos in 1808, after the battle of Gamonal, Napoleon had noted the commanding situation of the hill, and had determined to make it one of the fortified bases upon which the French domination in northern Spain was to be founded. He had caused a plan to be drawn up for the conversion of the ruined mediaeval stronghold into a modern citadel, which should overawe the city below, and serve as a half-way house, an arsenal, and a depot for French troops moving between Bayonne and Madrid.'

|

| Point 3 - The interior ceiling of the Arco de Santa Maria medieval gate house. |

The Battle of Salamanca was perhaps the turning point in the Peninsular War, as following this battle, the French had to totally reassess Wellington as a commander.

Formerly considered as a defensive specialist, which he certainly was, the situation had changed dramatically on the 23rd July 1812 as the French suddenly discovered the 'new Marlborough' was at hand with, for a short time after the battle, disruption caused to the dispositions of the Army of Portugal, at least what was left of it, under General Clausel, the centre under Joseph and the south under Soult.

With the Army of Portugal now too damaged to cause an immediate threat, Wellington was free to occupy the central position by advancing on Madrid, bringing up Hill with his southern corps as the French command decided what to do in reaction to this turn of events.

The immediate effect of Wellington's victory and advance on the Spanish capital was for Clausel to take what remained of the Army of Portugal away to the north and hopes of resupply, replenishment and reorganisation closer to the French homeland.

|

| A contemporary satirical sketch of the entry into Madrid by Wellington on the 12th August 1812 https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?assetId=75291&objectId=1487889&partId=1 |

In addition the advance on Madrid would eventually force Joseph to abandon his plans to join with Marmont, now wounded and with his army in retreat, and to leave his capital to Wellington who entered it in triumph on August 12th as the French King headed south to join forces with Marshal Suchet's army around Valencia; whilst sending urgent messages to Soult urging him to abandon Andalusia and the siege of Cadiz and join him at Valencia before Wellington would be able to turn and attack either of the French armies in detail.

|

| Allied and French Troop Movements, August and September 1812 adapted from 'Wellington's Worst Scrape' by Carole Divall. |

Wellington took the time to allow his army to bask in their triumph and recover from the gruelling last six months which had seen the successful, if bloody, sieges of Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajoz crowned with overwhelming victory at Salamanca and to choose his next move once those of his opponents became clear.

The choices that presented themselves were to fall on either the remains of the Army of Portugal and remove them from the French order of battle or to head south hoping to cut Soult off before he realised the peril his obfuscation and delay was putting his army in, whilst he disputed with Joseph the need for him to abandon his fiefdom and independence, to put the fortunes of the French hold on the peninsula first and foremost.

In the end, news reached Soult on the 18th August with the first official confirmation of the disaster of Salamanca that finally convinced him in the sense of a French withdrawal and by the 24th of the month the evacuation was well underway as the French lines around Cadiz were destroyed.

|

| Point 4- The 13th century Cathedral of St Mary of Burgos on the square behind the gatehouse |

However, Wellington's hand was forced somewhat, as Clausel, realising that Wellington was heading for Madrid rather than pursuing him, cautiously gave permission to General Foy to lead an advance against the allied communication lines via Salamanca with a move back towards the River Duero and Vallodolid, which was retaken on the 14th August.

The French advance allowed them to retrieve French garrisons left behind in their retreat, entering Zamora on the 25th August, before Wellington's attention to the north finally forced the French back to the Douro, with Wellington seemingly content for the French to recover their garrisons, thus not forcing him to have to take them out by force of arms.

The activities of the allies were not just focused on Wellington's and Hill's troops in the centre, but also a vigorous campaign launched against the northern coast by Commodore Home Popham in cooperation with the northern guerrillas against French garrison troops under General Caffarelli, that effectively prevented him from providing any worthwhile reinforcements to the Army of Portugal.

In addition, the largest and safest harbour between the French border and the Ferrol at Santander had been under attack by Popham and the guerrillas since the 22nd July with the result that General Dubreton and his 1,200 strong garrison abandoned the place on the night of the 2nd August.

Meanwhile on the eastern coast of Spain, Allied activities in the area forced Marshal Suchet to take a considered view of his situation, unsure if Wellington would follow Joseph and bring the war to his theatre of operation together with his concerns of further Anglo-Spanish operations against his front around Alicante, following the landing of an Anglo-Sicilian force after his defeat of a Spanish army at Castalla in June.

I covered these events on my visit to Castalla last year.

http://jjwargames.blogspot.com/2018/05/first-and-second-battles-of-castalla.html

|

Thus with the decision to to take full advantage of his success so far and with the year coming to a close, Wellington had to hold his forward position below the River Ebro, and to do that he needed push Clausel back over the river and take Burgos.

Prior to his leaving Madrid under its new Spanish governor, General Carlos de Espana, Wellington wrote to Major General Murray confirming his strategic intentions;

'I hear the siege of Cadiz is raised; and there is a storm brewing up from the south, for which I am preparing by driving the detachments of the Army of Portugal away from the Duero; and I propose, if I have time, to take Burgos from them.

In the meantime I have ordered Hill to cross the Tagus by Almaraz, when he shall find that Soult moves out of Andalusia ... I have, I hope, relieved General Maitland of all anxiety at Alicante, by taking upon myself all responsibility, and giving him positive orders for his conduct, so that he will only have to fight in a good position, his supplies being secured to him from the sea.

.... Matters go on well, and I hope before Christmas, if affairs turn out as they ought, and Boney requires all the reinforcements in the North, to have all the gentlemen safe on the other side of the Ebro.'

Oman further described the French development of their northern fortified depot;

'Considered as a fortress it had one prominent defect: while its eastern, southern, and western sides look down into the low ground around the Arlanzon river, there lies on its northern side, only 300 yards away, a flat-topped plateau, called the hill of San Miguel, which rises to within a few feet of the same height as the Donjon, and overlooks all the lower slopes of the Castle mount. As this rising ground—now occupied by the city reservoir of Burgos—commanded so much of the defences, Napoleon held that it must be occupied, and a fort upon it formed part of his original plan.

But the Emperor passed on; the tide of war swept far south of Madrid; and the full scheme for the fortification of Burgos was never carried out; money—the essential thing when building is in hand—was never forthcoming in sufficient quantities, and the actual state of the place in 1812 was very different from what it would have been if Napoleon's orders had been carried out in detail.

Enough was done to make the Castle impregnable against guerrillero bands—the only enemies who ever came near it between 1809 and 1812—but it could not be described as a complete or satisfactory piece of military engineering. Against a besieger unprovided with sufficient artillery it was formidable enough: round two-thirds of its circuit it had a complete double enceinte, enclosing the Donjon and the church on the summit which formed its nucleus. On the western side, for about one-third of its circumference, it had an outer or third line of defence, to take in the lowest slopes of the hill on which it lies. For here the ground descended gradually, while to the east it shelved very steeply down to the town, and an external defence was unnecessary and indeed impossible.

The outer line all round (i.e. the third line on the west, the second line on the rest of the circumference) had as its base the old walls of the external enclosure of the mediaeval Castle, modernized by shot-proof parapets and with tambours and palisades added at the angles to give flank fire. It had a ditch 30 feet wide, and a counterscarp in masonry, while the inner enceintes were only strong earthworks, like good field entrenchments; they were, however, both furnished with palisades in front and were also ' fraised ' above.

|

| The view out over Burgos from the foot of the castle hill |

The Donjon, which had been strengthened and built up, contained the powder magazine in its lower story. On its platform, which was most solid, was established a battery for eight heavy guns (Batterie Napoleon), which from its lofty position commanded all the surrounding ground, including the top of the hill of San Miguel.

The magazine of provisions, which was copiously supplied, was in the church of Santa Maria la Blanca. Food never failed—but water was a more serious problem; there was only one well, and the garrison had to be put on an allowance for drinking from the commencement of the siege. The hornwork of San Miguel, which covered the important plateau to the north, had never been properly finished. It was very large; its front was composed of earthwork 25 feet high, covered by a counterscarp of 10 feet deep. Here the work was formidable, the scarp being steep and slippery; but the flanks were not so strong, and the rear or gorge was only closed by a row of palisades, erected within the last two days.

The only outer defences consisted of three light fleches, or redans, lying some 60 yards out in front of the hornwork, at projecting points of the plateau, which commanded the lower slopes. The artillery in San Miguel consisted of seven field-pieces, 4- and 6-pounders: there were no heavy guns in it.'

Wellington left Madrid on September 1st leaving behind him, some 40,000 troops in and around the capital which included his three most experienced divisions at siege work, namely the Light, 3rd and 4th Divisions, whilst the two he chose to take with him, the 1st and 7th, were the most inexperienced.

The balance of the Allied army pursued the French north with Clausel's 22,000 strong force stopping every now and then on a ridge or behind a small river, forcing the Allies to deploy, as if ready to offer battle, before resuming their march before any serious fighting could start.

In this way the two armies eventually arrived before Burgos on the 18th September, which again saw Clausel deployed in front of the town before retiring yet again, leaving a garrison of 2,000 men under General Dubreton, the same officer who had evacuated Santander in August.

Wellington and his staff reconnoitred the castle and its defences and seems not to have been overly concerned with what he found, however Lieutenant Colonel Robe, Royal Artillery prophetically commented to Alexander Dickson in command of the Portuguese artillery that;

'we have had a view of the castle which appears a more tough job than we might have supposed.'

|

| The view looking towards the area of the Battle of Gamonal now covered in buildings, top left of picture |

Oman continues with his description of the French defenders;

'The garrison of Burgos belonged to the Army of the North, not to that of Portugal. Caffarelli himself paid a hasty visit to the place just before the siege began, and threw in some picked troops—two battalions of the 34th, one of the 130th; making 1,600 infantry. There were also a company of artillery, another of pioneers, and detachments which brought up the whole to exactly 2,000 men—a very sufficient number for a place of such small size.

|

| Officer and Voltigeur of the 34me Ligne as depicted by Bosselier - Two battalions from the regiment formed the bulk of the garrison at Burgos |

There were nine heavy guns (16- and 12-pounders), of which eight were placed in the Napoleon battery, eleven field-pieces (seven of them in San Miguel), and six mortars or howitzers. This was none too great a provision, and would have been inadequate against a besieger provided with a proper battering-train: Wellington—as we shall see—was not so provided. The governor was a General of Brigade named Dubreton, one of the most resourceful and enterprising officers whom the British army ever encountered. He earned at Burgos a reputation even more brilliant than that which Phillipon acquired at Badajoz.

The weak points of the fortress were firstly the unfinished condition of the San Miguel hornwork, which Dubreton had to maintain as long as he could, in order that the British might not use the hill on which it stood as vantage ground for battering the Castle; secondly, the lack of cover within the works.

The Donjon and the church of Santa Maria could not house a tithe of the garrison ; the rest had to bivouac in the open, a trying experience in the rain, which fell copiously on many days of the siege. If the besiegers had possessed a provision of mortars, to keep up a regular bombardment of the interior of the Castle, it would not long have been tenable, owing to the losses that must have been suffered.

Thirdly must be mentioned the bad construction of many of the works—part of them were mediaeval structures, not originally intended to resist cannon, and hastily adapted to modern necessities: some of them were not furnished with parapets or embrasures—which had, to be extemporized with sandbags.

Lastly, it must be remembered that the conical shape of the hill exposed the inner no less than the outer works to battering: the lower enceintes only partly covered the inner ones, whose higher sections stood up visible above them. The Donjon and Santa Maria were exposed from the first to such fire as the enemy could turn against them, no less than the walls of the outer circumference.

If Wellington had owned the siege-train that he brought against Badajoz, the place must have succumbed in ten days. But the commander was able and determined, the troops willing, the supply of food and of artillery munitions ample—Burgos had always been an important depot. Dubreton's orders were to keep his enemy detained as long as possible—and he succeeded, even beyond all reasonable expectations.'

Wellington had brought with him four division, the 1st, 5th 6th and 7th together with two independent Portuguese brigades, together with the small siege train he had used at Salamanca to deal with the French forts, namely, three 18-pounder guns and five 24-pounder carronades.

The siege artillery component has been generally and rightly criticised for not being sufficient to deal with even a minor fortress such as Burgos, and to compound the weakness, Wellington had insufficient stocks of powder, shot and shell that had the attackers worried about supply levels before the first shot was fired that would see the ridiculous situation of allied troops being offered bounties to recover any shot previously fired at the defences for reuse.

As well as deficiency in the artillery, Wellington also lacked in enough engineers and a corps of sappers and miners to lead the work only made worse by having with him his least experienced divisions at siege work.

|

| The satellite view shows clearly the limited remains of the castle with the tree covered slopes of San Miguel Hill above it |

As at Ciudad Rodrigo, Wellington commenced his siege with a rapid attack on an outlying fortified work to offer his gunners the best place to establish their batteries; and so on the morning of the 19th the fleches protecting the forward slopes of the St Miguel hill fort were attacked and captured by the light companies of the Highland Brigade (79th and 42nd Foot) commanded by Major Edward Charles Cocks of the 79th Cameron Highlanders.

|

| The 79th Cameron Highlanders as depicted by Bryan Fosten |

That evening Cocks was ordered to make a second attack on the rear of the main hornwork, to cause a distraction to the defenders and prevent reinforcements arriving from the castle or the defenders retreating back to it whilst a main assault was made on the front of the position under the cover of darkness.

The attack commenced at 8pm with Cocks leading his soldiers at the double, running along the side of the hill under heavy fire from the castle and the hornwork, which mowed down many on the race to get to the palisade at its rear.

Cocks closely followed by Sergeant John Mackenzie of the 79th reached it first and not waiting for the ladders, heaved each other over the palisades, followed by the survivors from the dash.

Sergeant Donald Mackenzie and Buglar Charles Bogie with a party of men guarded the escape route whilst the rest of the force rushed on into the works to begin a fierce hand-to-hand struggle.

Meanwhile the frontal attack had been driven off by the defenders, but the noise of the fighting to their rear unnerved the French soldiers sufficient for their resolve to break and cause them to make a headlong rush to evacuate the works, trampling over Mackenzie's and Bogie's party at the rear, as they made their escape back to the castle, leaving the works in the control of Cocks and his men.

Cocks wrote of the attack in a letter home to his friend and cousin Thomas Somers Cocks;

'Clausel, with the remains of Marmont's army, retired before us from Vallodolid, abandoning Burgos, where he left 2,000 men in a strong fort under the orders of General de Brigade de Bruton. A large outwork called the hornwork of San Miguel considerably added to the strength of this fort. The Marquis* resolved to assault it the night of the investment, the 19th, and I was entrusted with one attack with the light companies ....

We tumbled the garrison out, bayoneting 70, taking 70, and wounding from 2 to 300. In consequence of this the Marquis recommended me for a brevet lieut colonelcy ...

I think Burgos will fall about the 5th October; part of the force employed here will then probably move towards Madrid. Soult has evacuated all Andalusia. He is now near Jaen or Baeza. The French chiefs have no union; Suchet absolutely refused to go out of his quarters at Valencia for Joseph who, in consequence, removed to [?]. Soult hates both. If things continue to look well in the north I do not think there will be a Frenchman on this side of the Ebro in January ...'

* Wellington

Oman described the attack on the hornwork thus;

'The storm succeeded, but with vast and unnecessary loss of life, and not in the way which Wellington had intended. It was bright moonlight, and the firing party, when coming up over the crest, were at once detected by the French, who opened a very heavy fire upon them. The Highlanders commenced to reply while still 150 yards away, and then advanced firing till they came close up to the work, where they remained for a quarter of an hour, entirely exposed and suffering terribly. Having lost half their numbers they finally dispersed, but not till after the main attack had failed.

On both their flanks the assaulting columns were repulsed, though the advanced parties duly laid their ladders: they were found somewhat short, and after wavering for some minutes Pack's men retired, suffering heavily.

The whole affair would have been a failure, but for the assault on the gorge. Here the three light companies—140 men—were led by Somers Cocks, formerly one of Wellington's most distinguished intelligence officers, the hero of many a risky ride, but recently promoted to a majority in the l/79th. He made no demonstration, but a fierce attack from the first. He ran up the back slope' of the hill of St. Miguel, under a destructive fire from the Castle, which detected his little column at once, and shelled it from the rear all the time that it was at work.

The frontal assault, however, was engrossing the attention of the garrison of the hornwork, and only a weak guard had been left at the gorge. The light companies broke through the 7-foot palisades, partly by using axes, partly by main force and climbing. Somers Cocks then divided his men into two bodies, leaving the smaller to block the postern in the gorge, while with the larger he got upon the parapet and advanced firing towards the right demi-bastion.

Suddenly attacked in the rear, just as they found themselves victorious in front, the French garrison—a battalion of the 34th, 500 strong —made no attempt to drive out the light companies, but ran in a mass towards the postern, trampled down the guard left there, and escaped to the Castle across the intervening ravine.

They lost 198 men, including 60 prisoners, and left behind their seven field-pieces. The assailants suffered far more—they had 421 killed and wounded, of whom no less than 204 were in the l/42nd, which had suffered terribly in the main assault. The Portuguese lost 113 only, never having pushed their attack home. This murderous business was the first serious fighting in which the Black Watch were involved since their return to Spain in April 1812; at Salamanca they had been little engaged, and were the strongest British battalion in the field—over 1,000 bayonets. Wellington attributed their heavy casualties to their inexperience—they exposed themselves over-much.

' If I had had some of the troops who have stormed so often before [3rd and Light Divisions], I should not have lost a fourth of the number.'

With the hornwork now in Allied hands work to construct communication trenches to it began immediately despite the best efforts of the French garrison who opened up on the position from the Napoleon battery with a murderous fire that caused the withdrawal of all but three-hundred of the attackers.

Over the next two days the first battery position was set up and armed with two 18-pounder guns and three 24-pounder howitzers ready to open fire on the garrison the next day, and then Wellington changed the plan, as described by Oman;

' ... Wellington, encouraged by his success at San Miguel, had determined to try as a preliminary move a second escalade, without help of artillery, on the outer enceinte of the Castle. This was to prove the first, and not the least disheartening, of the checks that he was to meet before Burgos.

The point of attack selected was on the north-western side of the lower wall, at a place where it was some 23 feet high. The choice was determined by the existence of a hollow road coming out of the suburb of San Pedro, from which access in perfectly dead ground, unsearched by any of the French guns, could be got, to a point within 60 yards of the ditch.

|

| The view looking down the slope from the western castle walls reveals the remains of the first French ditch and palisade. |

The assault was to be made by 400 volunteers from the three brigades of the 1st Division, and was to be supported and flanked by a separate attack on another point on the south side of the outer enceinte, to be delivered by a detachment of the cacadores of the 6th Division. The force used was certainly too small for the purpose required, and it did not even get a chance of success. The Portuguese, when issuing from the ruined houses of the town, were detected at once, and being heavily fired on, retired without even approaching their goal.

At the main attack the ladder party and forlorn hope reached the ditch in their first rush, sprang in and planted four ladders against the wall. The enemy had been taken somewhat by surprise, but recovered himself before the supports got to the front, which they did in a straggling fashion. A heavy musketry fire was opened on the men in the ditch, and live shells were rolled by hand upon them. Several attempts were made to mount the ladders, but all who neared their top rungs were shot or bayoneted, and after the officer in charge of the assault (Major Laurie, l/79th) had been killed, the stormers ran back to their cover in the hollow road.

They had lost 158 officers and men in all—76 from the Guards' brigade, 44 from the German brigade, 9 from the Line brigade of the 1st Division, while the ineffective Portuguese diversion had cost only 29 casualties. The French had 9 killed and 13 wounded.

This was a deplorable business from every point of view. An escalade directed against an intact line of defence, held by a strong garrison, whose morale had not been shaken by any previous artillery preparation, was unjustifiable.'

General Dubreton was justifiably proud of his men when he wrote in his dispatch;

'the assault jas been received with vigour by five companies of the second battalion of the 34th of the line. A few of the assailants reached as far as the parapet, but they were knocked over, and the rest put to flight by our fusilade and by the loaded shells which we rolled into the ditch . . . The enemy suffered greatly in this action, and left in the ditches the shells which they had brought, and about forty dead, including three officers. There were a great number of wounded, if one judges by the wreckage abandoned at the point of attack.'

Ensign John Mills, 2nd Coldstream Guards had this scathing comment on the attack;

'Our men got the ladders up with some difficulty under a heavy fire from the top of the wall, but were unable to get to the top. Hall of the 3rd Regiment [3rd Foot Guards] who mounted first was knocked down. Frazer tried and was shot in the knee. During the whole of this time [the French] kept up a constant fire from the top of the wall and threw down bags of gunpowder and large stones.

At last, having been twenty-five minutes in the ditch and not seeing anything of the other parties they retired having lost half their numbers in killed and wounded. 3 officers were wounded. The Portuguese failed in their attempts. Thus ended the attack which was almost madness to attempt.'

Following the bloody repulse of the 22nd, the plan of attack reverted back to a more considered approach with mining operations commenced against the outer wall and No.1 battery opened fire on the 25th, drawing this comment from Alexander Dickson at the end of the first day;

'it being found by the want of precision in the [24-pounder] howitzers with round shot, a greater expenditure of ammunition would be required . . . than the limited means . . . could afford'

It seems ten percent of the available round shot was used in that first day to discover that the guns were highly inaccurate, forcing a a bounty to be offered to the soldiers to return every round shot they could for reuse, even those of the wrong calibre, which were duly paid for!

Wellington was also forced to turn to the Royal Navy for help with additional supplies when he wrote to Sir Home Popham on the 26th September;

'I am very much in want of 40 barrels of gunpowder, each containing 90 pounds, for the attack of this place; and I should very much be obliged to you if you could let me have this quantity from the ships under your command.'

The next day he sent a further request for biscuit commenting;

'We are getting on very rapidly, and I do not feel certain that I shall succeed, as I have very little artillery and stores for my object; but I hope I may succeed.'

The mining operations were hampered too with a lack of specialist sappers and miners, together with tools for work underground, however promising progress was made by digging out the hollow road from the suburb of San Pedro (see Oman's map above) and creating the first parallel, making use of the summit of the bank to open the ground undetected by the garrison above.

To further protect the 250 strong work party, a firing trench was built across the parallel to offer defensive fire but sharpshooters placed by Dubreton in a nearby projecting palisade took a steady toll of the men as they worked ever closer.

In addition to the progress from San Pedro, a second battery position was started on San Miguel Hill, together with a firing trench constructed in front of the first battery position which drew an almost immediate response from the gunners on the Napoleon battery as noted by Lt. Colonel John Jones of the Royal Engineers;

'the showering of grape-shot which fell without intermission all round the spot, causing an incessant whizzing and rattling amongst the stones, appeared at that moment to be carrying destruction through the ranks; but, except the necessity of instantly carrying off the wounded, on account of their sufferings, it caused little interruption to the workmen.

It was remarked here, as it has been on former occasions, that a wound from a grape-shot is less quietly borne than a wound from a round-shot or musketry. The latter is seldom known in the night, except from the falling of the individual; whereas the former, not infrequently, draws forth loud lamentations.'

|

| One of the plans around the castle walls which helps to bring some sense to the remains that can be seen |

By the 27th of September the first mine was making good progress and work had started on the building of a second, despite the constant defensive fire taken from the defenders.

However it seems Dubreton had anticipated the Allied tactic when he noted on the 25th that;

'Always presuming that the enemy will make a breach with a mine, we have prepared several means of obstacles to push back the assault.'

Despite the unexpectedly robust resistance from the French garrison, Wellington could at least draw comfort from the wider situation with regard to the Army of Portugal seeing Clausel content to sit on the left bank of the Ebro, dispersing his troops, as he sought to rebuild his force.

By the 27th work by the French was discovered by the Allies showing the construction of a covered way to their middle line of defences, suggesting a possible withdrawal from the outer line if pressed.

|

| Looking back along the route up from the town |

By the 29th the first mine was forty-two feet long and the second thirty-two feet; the first having come up against solid masonry suggesting the foundation of the scarp wall had been reached. A five foot powder chamber was constructed and filled with twelve barrels each containing ninety pounds of powder.

With the fuse laid in a wooden channel, the tunnel was packed with bags of earth for fifteen feet to force the explosion up and by 22.00 the mine was ready to be fired.

Lt Colonel Jones RE picks up the account of the firing of the mine;

'At midnight a storming party of 300 men, having been paraded in the lower town, and a working party, with the necessary tools and materials, being in their rear to form a lodgement, the mine was sprung.

The explosion made very little report, but brought the wall down, The earth of the rampart behind the ruined scarp remained very steep, but next the broken parts of the wall, on both sides, the ascent was easy.'

The breach was not as extensive as hoped and Jones postulates that perhaps the explosives were laid against an older foundation rather than that of the wall. The lack of damage to the wall was only compounded when, due to a lack of engineer officers to lead the forlorn hope to the breach, they became lost with just a sergeant and four men finding their way to and into it only to be driven back at the point of the bayonet as a French counterattack sealed of the breach.

The shortage of engineer officers was having a direct effect on the operation as the few that were with the army were now either dead or wounded except their commander, now Colonel John Burgoyne who we first met in my post looking at the destruction of Fort Concepcion, recovering from being hit in the head by a spent musket ball.

The lack of artillery to was not helping matters, as the lack of support fire in the next preceding days failed to prevent the French garrison from building a parapet behind the breached section of wall.

|

| The road up from the town leads along the western wall |

The lack of progress and the continual drain of casualties being suffered over the first twelve days of the siege was taking effect on the Allied troops with a growing loss of confidence in the engineers and the commander-in-chief.

The situation reached a low point on the 2nd October when the whole of the working party for the night, except those from the Guards regiments, failed to turn up, resulting in a stinging rebuke from Wellington and several officers being arrested for neglect of duty.

One particular problem was that the working parties were now so close to the French defences that anybody putting their head above the parapet was immediately shot by the French sharpshooters, causing the Allies to reposition one of the captured French six-pounders from the hornwork to batter down one particularly annoying stockade, taking three hours to get the position destroyed.

In the next few days work continued preparing the second mine and to construct a second battery position on San Miguel hill. Unfortunately the French had discovered the latter work before the battery got a chance to open fire, and they pounded it mercilessly, damaging two of the three guns that Wellington had and forcing them to be remounted later on temporary carriages causing them to have to be fired with reduced charges and thus at reduced effect for the remainder of the siege.

|

| Looking down into the gorge between Castle and San Miguel Hill. |

Wellington, it seems was realistic about the situation, writing in his dispatches;

'I am very afraid that I shall not take this castle. It is very strong, well-garrisoned, and well provided with artillery. I had only three pieces of cannon, of which one was destroyed last night, and not much ammunition; and I have not been able to get on as I ought.

I have, however, got a mine under one of the works, which I hope will enable me to carry the exterior line; and when that shall be carried, I hope I shall get on better. But time is wearing apace, and Soult is moving from the South; and I shall not be surprised if I were obliged to discontinue this operation in order to collect the army.'

On October 4th No.1 battery opened fire on the breach created by the first mine as recounted by Oman;

'At dawn, battery No. 1 opened on the wall, where it had been damaged by the first mine on September 29th, using the two 18-pounders and three howitzers. The effect was much better than could have been expected: the 18 lb. round-shot (of which about 350 were used) had good penetrating power, and the already shaken wall crumbled rapidly, so that by four in the afternoon there was a practicable breach sixty feet long.

Wellington at once arranged for a third assault on the outer enceinte, telling off for it not details from many regiments, as on the previous occasion, but—what was much better—a single compact battalion, the 2/24th. Only the supports were mixed parties.

|

| My interpretation of the 2/24th for Talavera 208 https://jjwargames.blogspot.com/2014/12/24th-warwickshire-regiment-foot-howards.html |

At 5 p.m. the mine was fired, with excellent effect, throwing down nearly 100 feet of the rampart, and killing many of the French. Before the dust had cleared away, the men of the 2/24th dashed forward toward both breaches, with great spirit, and carried them with ease, and with no excessive

loss, driving the French within the second or middle enceinte.

The total loss that day was 224, of which the assault cost about 190, the other casualties being in the batteries on San Miguel and in the trenches. But the curious point of the figures is that the 2/24th, forming the actual storming-column, lost only 68 killed and wounded; the supports, and the workmen who were employed to form a lodgement within the conquered space, suffered far more heavily.

Dubreton reports the casualties of the garrison at 27 killed and 42 wounded.'

Among the Allied wounded was Colonel John Jones RE, a wound to the ankle that forced the officer to return to England, which allowed him to complete his comprehensive work on the British Sieges of the Peninsular War published in 1814. Perhaps more importantly at the time, his wounding left Wellington with one less highly experienced engineer.

|

| The view along the eastern wall of the castle |

The French launched two sorties on the 5th and 8th of October causing some damage, but the real damage to the morale of the Allied army was already severe and the army was losing heart.

Oman described the French attack on the 8th October;

'On October 8 Dubreton, growing once more anxious at the sight of the advance of the trenches toward the second enceinte, ordered another sally, which was executed by 400 men three hours after midnight.

It was almost as successful as that of October 5. The working party of Pack's Portuguese and the covering party from the K.G.L. brigade of the 1st Division were taken quite unawares, and driven out of the advanced works with very heavy loss. The trench was completely levelled, and many tools carried away, before the supports in reserve, under Somers Cocks of the l/79th—the hero of the assault on the Hornwork—came up and drove the French back to their palisades.

Cocks himself was killed—he was an officer of the highest promise who would have gone far if fate had spared him, and was the centre of a large circle of friends who have left enthusiastic appreciations of his greatness of spirit and ready wit.

The besiegers lost 184 men in this unhappy business, of whom 133 belonged to the German Legion: 18 of them were prisoners carried off into the Castle.

The French casualties were no more than 11 killed and 22 wounded—only a sixth part of those of the Allies.'

|

| The view along the northern wall facing San Miguel Hill |

Dubreton described the sortie from the French perspective;

'Two companies of grenadiers, two sections of voltigeurs and a detachment of pioneers and workers came out rapidly and marched so precisely to the enemy's communication trenches with the parallel that everyone in the entrenched camp, with the exception of two English officers and thirty-six soldiers made prisoner, was bayoneted by the voltigeurs and buried in the trenches.

Our troops, after having filled in the enemy's works, made their retreat in good order. During this sortie we lost an officer and six men killed, two officers and twenty men wounded.'

Captain William Tomkinson, a close friend of Cocks from when they served together in the 16th Light Dragoons, was distressed to hear the report of his friends death when he went to the camp of the 79th to get more details;

'He fell by a ball which entered between the fourth and fifth rib on the right side, passing through the main artery immediately above the heart, and so out the left side, breaking his arm; the man was close to him. In Cocks, the army has lost one of its best officers, society a worthy member, and I a sincere friend.'

Wellington wrote a letter of condolence to Cocks's father Lord Somers in which he stated;

'Your son fell as he lived, in the zealous and gallant discharge of his duty . . . and I assure your Lordship that if Providence had spared him to you, he possessed acquirements, and was endowed with qualities, to become one of the greatest ornaments of his profession, and to continue an honour to his family, and an advantage to his country.'

They buried him the next morning under a cork tree in the 79th's ground at Bellima. Attended by Lord Wellington, Sir Stapleton Cotton, Generals Pack and Anson and the whole of their staffs and the officers of the 16th Light Dragoons and 79th Regiment; Cocks funeral proved to be one of those rare occasions that Wellington shed a tear.

Following the French sortie no further attempts were made to push the works forward and the Allies contented themselves with firing from their two batteries, with No.2 causing a practical breach in the middle line, twenty to twenty-five feet wide at the junction of the middle and outer lines (Breach III on Oman's map) and No.1 targeting the keep of the castle.

After dark a zig-zag trench was dug to within thirty yards of the new breach and the Guards managed to put down enough musketry to drive off French attempts to repair it.

The next day on the 9th, hot shot was fired against the church of Santa Maria La Blanca causing some smoke to be observed rising from the building but no general conflagration and work commenced on a final mine fifty yards out from and aimed at the church of San Roman.

Wellington described the situation in a letter to Beresford;

'We have a practicable breach in the second line, notwithstanding that all our guns and carriages are what is called destroyed; and I am now endeavouring to set fire the magazine of provisions.

I cannot venture to storm the breach. We have used such an unconscionable amount of musket ammunition, particularly in two sorties, made by the enemy, one of the 5th and the other yesterday morning, that I cannot venture to storm until I am certain of the arrival of a supply.

I have sent to the rear and to Santander; and we are making some. But I have not yet heard of any approaching, I fear, therefore, that we must turn our siege into a blockade.'

If that wasn't bad enough rumours were circulating that the Army of Portugal had received reinforcements of 10,000 infantry and 1,500 cavalry from the Army of the North and was concentrating on Pancorvo (see Oman's map of the campaign area at the top of the post).

Oman picks up the account of the final assault on Burgos before the situation elsewhere forced the Allies to break off;

'On the 18th the engineers reported that the church of San Roman was completely undermined, and could be blown up at any moment. On the same morning the one good and two lame 18-pounders in battery 2 on San Miguel swept away, not for the first time, the sandbag parapets and chevaux defrise with which the French had strengthened the breach III. They were then turned against the third enceinte, immediately behind that breach, partly demolished its fraises,' and even did some damage to its rampart.

This was as much as could have been expected, as the whole of the enemy's guns were, as usual, turned upon the battering-guns, and presently obtained the mastery over them, blowing up an expense-magazine in No. 2, and injuring a gun in No. 1.

But in the afternoon the defences were in a more battered condition than usual, and Wellington resolved to make his last attempt. Already the French army outside was showing signs of activity; and, as a precaution, some of the investing troops—two brigades of the 6th Division—

had been sent forward to join the covering army. If this assault failed, the siege would have to be given up, or at the best turned into a blockade.

The plan of the assault was drawn up by Wellington himself, who dictated the details to his military secretary, Fitzroy Somerset, in three successive sections, after inspecting from the nearest possible point each of the three fronts which he intended to attack.

Stated shortly the plan was as follows:

(1) At 4.30 the mine at San Roman was to be fired, and the ruins of the church seized by Brown's cacadores (9th battalion), supported by a Spanish regiment (1st of Asturias) lent by Castanos. A brigade of the 6th Division was to be ready in the streets behind, to support the assault, if its effect

looked promising, i.e. if the results of the explosion should injure the enceinte behind, or should so drive the enemy from it that an escalade became possible.

(2) The detachments of the Guards' brigade of the 1st Division, who were that day in charge of the trenches within the captured outer enceinte, and facing the west front of the second enceinte, were to make an attempt to escalade that line of defence, at the point where most of its palisades had been destroyed, opposite and above the original breach No. I in the lower enceinte.

(3) The detachments of the German brigade of the 1st Division, who were to take charge of the trenches for the evening in succession to the Guards, were to attempt to storm the breach III in the re-entering angle, the only point where there was an actual opening prepared into the inner defences.

From all the works, both those on St. Miguel and those to the west of the Castle, marksmen left in the trenches were to keep up as'hot a musketry fire as possible on any of the enemy who should show themselves, so as to distract their attention from the stormers.'

The mine was blown under San Roman on the 18th October 1812 as four-hundred Allied troops assaulted the second line as described by Oman;

'On the explosion of the mine at San Roman, punctually at 4.30, all three of the sections of the assault were duly delivered. At he breach the forlorn hope of the King's German Legion charged at the rough slope with great speed, reached the crest, and were immediately joined by the support, led most gallantly by Major Wurmb of the 5th Line Battalion. The first rush cleared a considerable length of the rampart of its defenders, till it was checked against a stockade, part of the works which the French had built to cut off the breach from the main body of the place.

Foiled here, on the flank, some of the Germans turned, and made a dash at the injured rampart of the third line, in their immediate front: three or four actually reached the parapet of this inmost defence of the enemy. But they fell, and the main body, penned in the narrow space between the two enceintes, became exposed to such an overpowering fire of musketry that, after losing nearly one man in three, they finally had to give way, and retired most reluctantly down the breach to the trenches they had left. The casualties out of 300 men engaged were no less than 82 killed and wounded 2, among the former, Wurmb, who had led the assault, and among the latter, Hesse, who commanded the forlorn hope, and was one of the few who scaled the inner wall as well as the outer.

|

| An illustration of the original gate house to the castle |

The Guards in their attack, 100 yards to the right of the breach, had an even harder task than the Germans, for their storm was a mere escalade. It was executed with great decision: issuing from the front trench they ran up to the line of broken palisades, passed through gaps in it, and applied their ladders to the face of the rampart of the second enceinte. Many of them succeeded in mounting, and they established themselves successfully on the parapet, and seized a long stretch of it, so long that some of their left-hand men got into touch with the Germans who had entered at the breach.

|

| Private of the 2nd 'Coldstream' Guards |

But they could not clear the enemy out of the terre-pleine of the second enceinte, where a solid body of the French kept up a rolling fire upon them, while the garrison of the upper line maintained a still fiercer fusillade from their high-lying point of vantage. The Guards were for about ten minutes within the wall, and made several attempts to get forward without success. At the end of that time a French reserve advanced from their left, and charging in flank the disordered mass within the enceinte drove them out again.

The Guards retired as best they could to the advanced trenches, having lost 85 officers and men out of the 300 engaged.

The French returned their casualties at 11 killed and 30 wounded.'

Total Allied casualties are estimated to have been 160 men. Two days later Wellington lifted the siege with the French armies massing and clearly threatening his position.

|

| The remains of the foundations of the castle gatehouse seen from the walls above. |

The Army of Portugal now numbered some 38,000 men and together with a large detachment from the Army of the North, brought total French forces between Pancorvo and Briviesca to just under 50,000 men with the new commander General de Division Souham, who replaced Marshal Marmont at the recommendation of Marshal Massena after he had turned down a return to his old job.

Allied losses during the twenty-six day siege were 550 killed and 1,550 wounded plus the loss of three guns.

The French lost 304 killed and 323 wounded plus 60 captured.

|

| The remains of the medieval wall can be seen from the castle, this view looking towards position '6' on my route map at the top of the post. |

As well as the Army of Portugal marching on Burgos, Joseph had united with Soult's army in October and on the 15th marched on Madrid at the head of 61,000 men and 84 guns.

Wellington managed to slip away from Burgos undetected on the 21st October falling back behind the River Pisuerga at Torquemada.

After a four day struggle as Wellington tried to prevent a French crossing, his position was finally turned forcing him to retreat and order General Hill to do the same, leaving Madrid to Joseph as he fell back to meet Wellington at Alba de Tormes on November 8th.

On November 15th Wellington found himself back at the old battlefield of Salamanca, the scene of his triumph earlier that summer, facing off Soult with 65,000 Allied troops against 80,000 French.

Perhaps his hat was worth at least a corps on any battlefield that day as Soult refused any ideas to attack; contenting himself with a cavalry pursuit as the demoralised and disordered Allied troops staggered back to Ciudad Rodrigo, losing some 5000 men in the retreat and putting the final cap on what had promised to have been an amazing year in the fortunes of Wellington and his army only to see themselves back where they had started the previous January with plenty of recriminations to follow.

Lt. Colonel Jones later wrote;

'A siege is one of the most arduous undertakings on which troops can be employed, - an undertaking in which fatigue, hardships, and personal risk, are the greatest, - one in which the prize can only be gained by complete victory, and where failure is usually attended with severe loss or dire disaster.

Success or failure of a siege frequently decides the fate of a campaign, sometimes of an army . . .'

|

| The view towards San Miguel hill covered in trees and with the former position of the Napoleon battery behind the castle wall directly ahead. |

I came away from Burgos feeling that there was a lot more the site could tell the visitor, with more work needing to be done to put what is visible into better context than the way it is now.

For me the castle still caries the melancholy of the events that happened there so long ago and the account of this most difficult of sieges and the retreat that followed, makes the events of 1813 even more extraordinary, when Wellington would come back into Spain with an allied army even stronger and better prepared than the one he marched with the previous year, a story I will pick up in the concluding post of this series as Carolyn and I travel up to Vitoria prior to heading home.

Sources consulted in the preparation of this post;

Intelligence Officer in the Peninsula, Letters & Diaries of Major The Hon. Edward Charles Cocks 1786 - 1812 - Julia Page

Wellington's Worst Scrape, The Burgos Campaign 1812 - Carole Divall

Wellington's Engineers, Military Engineering in the Peninsular War 1808-1814 - Mark S. Thompson

History of the Peninsular War Vol VI - Sir Charles Oman.

For a really well illustrated account of the various Allied assaults during the siege of Burgos, The British Battles site does an excellent job and is well worth visiting for greater clarity.

https://www.britishbattles.com/peninsular-war/attack-on-burgos/

Another fascinating report - thank you. My abiding memory of Burgos Castle is finding a carbine/pistol ball on a patch of recently disturbed ground. Could have been from anytime in 100+ years but, or course, I'm CERTAIN it's a relic of the 1812 siege!!!! Spent the rest of my trip staring closely at the ground.

ReplyDeleteSuperb post!! Thanks to share all these info and picts!

ReplyDeleteGreat report, good reading. I’m trying to find out where the 79th camp was during this siege. Bellima or Bellema is mentioned in the texts, but unlike all of the other locations, it seems impossible to find... any ideas?

ReplyDeleteHi Luke,

DeleteThank you glad you enjoyed the read.

As you will see I refer to the 79th's camp at Bellima in my account of the death of Cocks, but unfortunately, due to lack of time, I was not able to explore the area more widely than covered in my account.

Other than the usual exploits of general research I cannot offer much help other than I can highly recommend the Spanish 1:25000 walking maps I was using, sadly not for the Burgos area, but that helped me to identify some of the smaller hamlets mentioned in accounts from the time although names of places can change in two hundred years.

You may also find that the area you seek is no longer what it was with the development that has occurred in Spain in recent times and we found that aspect most obvious at Vitoria just up the road.

Sorry I can't be more helpful and good luck with your investigation.

JJ

Seems Bellima is Villimar. Someone is also trying to find more info here https://x.com/burgosconstruye/status/1699502328007557140?s=46&t=gE4bUYMg8aoHuHlcfoH82g

DeleteOk thank you for the update.

DeleteI am a bit of a chump, even my limited knowledge of Spanish reminds me that 'V' is pronounced 'B', hence 'Balencia' instead of 'Valencia' as it would be in English.

The map at the top of the post illustrating the Battle of Gamona actually shows the town of Vellimar or the Spanish pronounced Bellimar on the River Ruvena.

JJ