Corunna Retreat - Peninsular War Tour 2019

Following the battle of Bussaco (see link above and to the other posts in the series) and the French turning of the position in the afternoon of the 27th September 1810, the Allied retreat recommenced to Lisbon, followed by the French expecting to find a British army in full preparation to evacuate the country, courtesy of the Royal Navy, and an end to the campaign.

Coimbra was taken, though the bounty of much needed provisions stored in the towns warehouses was not to prove as useful as Massena had hoped and much to his annoyance; as the uncontrolled battalions of Junot's VIII Corps ravaged the town on its passage through, carelessly destroying food-stocks they could not carry and making up for the inability of the Allies to destroy them themselves before they evacuated.

|

| General Louis-Pierre Montbrun commanded the Cavalry Reserve Division of the Army of Portugal consisting of six regiments of dragoons |

On the 11th October General Montbrun's cavalry found their advance towards Lisbon blocked by a series of hills surmounted by a line of fortifications, and when the General reconnoitred the position in detail, he reported to Massena that the chain of forts extended many miles, prompting the Marshal to come forward to see for himself.

Redoubts and forts, close enough to support each other with artillery fire, extended for miles amid the hills and broken country with many of the streams and watercourses dammed, adding flooded areas to further impede an attacker; backed up by long lines of trenches, wooden stakes and barriers designed to slow any progress whilst under fire from the guns within the forts.

|

| Marshal Andre Massena, commander of the Army of Portugal |

Following a further extensive reconnaissance of the lines and some probing of the defences to test the Allied defence, with Massena personally inspecting the lines himself and growing more and more despondent as he began to appreciate their strength; even coming under fire himself at Arruda whilst walking away from a wall he had just been inspecting a position from with his glass, it became obvious that the French did not have the strength to force the defences backed up as they were by the Allied army.

Their followed the inevitable round of recriminations as to how it was that the Marshal was not informed of the state of Allied defences around Lisbon, with his army now amid hostile country, bereft of supplies in front of an Allied army with full supplies and reinforcement available from the sea.

On the 14th November Massena moved his army back from the lines to winter around Santarem on the River Tagus, constructing field works of his own deciding to wait the situation out in the hope of further reinforcements in the spring.

Massena received news that on the 14th December, General D'Erlon's IX Corps had arrived at Almeida to reinforce his position, however D'Erlon was in an impossible situation, under orders from the Emperor to not only reinforce Massena but also to use his troops to guard the line of communication to him from the Spanish border, in the end only managing to send forward another 6,000 men that only added to the problem of inadequate supplies.

As the winter months passed and the hardships endured by the Army of Portugal increased, Massena knew the time was coming to begin a retreat, prompting Wellington to write;

"It is wonderful that they have been able to remain in the country so long, and it is scarcely possible that they can remain much longer. If they go, and when they go, their losses will be very great and mine nothing. If they stay they must continue to lose men daily as they do now ..."

On the 5th March 1811, after months of bickering and conflicting advice from his corps commanders and in the face of expressed opposition from some of them, Massena ordered the French retreat north, but, wanting to keep his options open, with no precise final destination indicated.

Retreating in three columns, slowly and quietly, with surplus equipment and unnecessary baggage destroyed, allowing horses to be used for towing guns and with straw dummies and false canon left in forward positions, the French troops trudged north accompanied by hundreds of sick comrades.

The Allies were caught somewhat off-guard by the French withdrawal, with the enemy gaining a day's march on them before the extent of their pull-out was discovered; but the pursuit was commenced as soon as it was discovered, following the trail of smoke columns in the wake of the French army as it seemingly took out its wrath on the Portuguese civilians and their villages that it passed through.

Ney's VI Corps performed the role of rearguard and successfully fended off the Allied pursuit several times, finally, deciding to turn and hold the Allied pursuit at Pombal on the 11th March 1811, to delay the Allied advance while Montbrun's advance guard secured Coimbra.

On the 10th March Wellington wrote;

"The enemy still continue on their ground in front of Pombal, but not, I think, in the strength they were yesterday. They are still, however, very strong; and my own opinion is, that they will draw off the corps which they have there in the course of this night. If they do not, I propose to attack them there to-morrow. I think it most likely that they will go back as far as Condeixa, where they will collect their force with more ease than they can at Pombal."

The village of Pombal sits on the River Arunca with its prominent 12th century Templar castle sat above it and with a line of hills behind running parallel with the road to Redinha.

The description of the action at Pombal that followed is taken from 'The History of the the Peninsular War - Volume IV' by Sir Charles Oman;

'Ney, apparently having detected the arrival of British reinforcements, then drew back one of his divisions, and left the other (Mermet) in position on the heights behind the town, with a single battalion holding the lofty but ruined castle which dominates the place.

|

| Pombal Castle, built in the 12th century by Gualdim Pais, Master of the Templar Knights, and occupied and badly damaged by French troops in 1811, the castle was restored in 1940. |

|

| The 3rd Cacadores crossed the bridge at Pombal capturing the town from French troops occupying it before being counterattacked and driven out themselves |

Wellington, on perceiving that the enemy was drawing back, ordered Elder's battalion of Cacadores (3rd Cacadores) supported by two companies of the 95th Rifles, to charge across the bridge and occupy the town, while the rest of the Light Division advanced in support, and Picton moved to the left, to cross the stream lower down. The attacking force passed the narrow bridge under fire, cleared the nearer streets and assailed the castle and the small force left there.

Seeing his rearguard in danger of being cut off, and noting that Elder's force was small, Ney came down from the heights with four battalions** of the 6th Leger and the 69th Ligne, thrust back the Cacadores and the supporting rifle companies, and brought off the troops in the castle. He barricaded the main street, and set fire to the houses along it in several places before departing; these precautions detained for some minutes the main column of the Light Division, which was hurrying up to reinforce its van.

|

| The view from the battlements looking to the south with the higher ground behind Pombal visible |

The French were all retiring up the hill before they could be got at, and only suffered a little from Ross's guns, which were hurried up to play upon the retreating column, as it re-formed in the position beyond Pombal. By the time that the Light Division had disentangled itself from the burning town, and Picton had crossed the stream on the left, the day was far spent; and Ney retired at his leisure after dark, without having been further incommoded. The British followed, and encamped on the further side of the water, ready for pursuit next morning.

|

| The high-ground directly behind and next to the castle was occupied by Ney's reserves who descended into the town to eject the 3rd Cacadores and 95th Rifle companies |

Ney was much praised for the tactical skill which he had shown in saving his rearguard, and Erskine* was thought to have handled the Light Division clumsily. The French losses, trifling as they were, much exceeded those of the Allies—they lost four officers and fifty-nine men, all in the 6th and 69th.

|

| One of the modern day bridges as seen from the castle at Pombal. The 3rd Cacadores stormed the bridge and captured the town before Ney counterattacked. |

The Cacadores lost ten rank and file killed, and an officer and twenty men wounded—the two companies of the 95th had an ensign and four men wounded—a total of thirty-seven, little more than half the French loss.'

----------------------------------------------

* The reference to Erskine, is to Major General, Sir William Erskine who took command of the Light Division following General Craufurd taking home leave. On hearing of Sir William's departure for the Peninsular, Wellington wrote to Horse Guards complaining that he "generally understood him to be a madman", to which the reply came back that, "no doubt he is some times a little mad, but in his lucid intervals he is an uncommonly clever fellow; and I trust he will have no fit during the campaign, though he looked a little wild as he embarked."

** The French regiments detailed in Oman's text were Macaune's brigade, part of Marchand's division with two battalions of the 6th Legere and three battalions of the 69th Ligne

----------------------------------------------

Lieutenant George Simmons of the 95th Rifles, now recovered from the wound he received at the Action on the Coa described the fight for Pombal;

"The enemy moved off before day, and our cavalry and Horse Artillery set out in pursuit of it. They were obliged to halt a little way from Pombal, and the Light Division were sent forward to dislodge the enemy's Light Infantry and Voltigeurs from the enclosures. The castle, an old ruin situated upon an eminence, was very spiritedly attacked by the 95th Rifles and the 3rd Cacadores.

Although the enemy disputed the ground obstinately, which, from the nature of it, was very defensible, yet they were driven sharply through Pombal, Some officers' baggage was captured.

The enemy remained on strong ground at a little distance from us. The 1st, 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th Divisions arrived near us in the course of the evening. The town of Pombal is frightfully dilapidated, and the inhabitants as miserable as I have before represented them in other places."

|

| The 6eme Legere were in the forefront of Ney's defence at Pombal, Casal Novo and Foz d'Arouce |

Captain Perre-Francois Guingret of the 6th Legere also described the action from the French perspective:

"The 6eme Legere, of which I was part, formed the extreme rearguard: the enemy pushed us vigorously .... I remember that a (shrapnel) shell removed a whole section of my company."

The retreat continued the next day, with VI Corps taking up a strong position on the 12th either side of the Redinha river, covering the important bridge through the town from the high ground.

Again Massena impressed upon Ney the importance of holding this ground for as long as possible whilst the retreat of the rest of the army continued.

Mermet's division was supported with fourteen guns and cavalry from the 3rd Hussars, 6th and 11th Dragoons, with Marchand's division on the opposite bank covering the bridge and the withdrawal route.

The town of Redinha proudly displays its Peninsular War heritage with its memorial to the battle close by the road into town.

Sadly much of the ridge held by Mermet and the Allied brigades on their approach to it is now under thick forestry or 'wood' as George Simmons described it, with not much prospect of gauging the nature of the ground, and so I focused my attention on the area around the bridge and the higher ground behind it occupied by Marchand.

|

| The Battlefield Memorial commemorating the two hundredth anniversary |

Lieutenant Simmons of the 95th Rifles described the action at Redinha as the Allies advanced on Ney's rearguard;

"The enemy took up a position to receive our attack in front of Redinha, his right resting on the river Soure, protected in front by heights covered with wood, and his left beyond Redinha upon the river.

|

| The road leading down from the ridge held by Mermet's division at Point 1 on the map. The picture illustrates the heavily wooded nature of the terrain in front of the town. |

The front part of his line was much intersected with deep ravines. In the centre was a beautiful plain filled with infantry, formed in good order but a motley-looking set of fellows in greatcoats and large caps, a body of cavalry supporting, and other bodies moving according to circumstances.

|

| The tile display although showing some questionable attention to detail seems to capture Simmons description of the French; "a motley-looking set of fellows in greatcoats and large caps" |

The wooded heights were attacked by a wing of the 1st Battalion (Rifles), commanded by Major Stewart, who carried them in gallant style. The other wing attacked the left, the Light Division acting in unison with these attacks, our columns moving rapidly into the plain, forming line and moving on, and also the cavalry.

|

| The bridge that formed the focal point of the action, pictured at Position 2 on the map |

It was a sunshiny morning, and the red coats and pipeclayed belts and glittering of men's arms in the sun looked beautiful. I felt a pleasure which none but a soldier so placed can feel. After a severe struggle we drove the enemy from all his strongholds and down a steep hill to the bridge. We pushed the fugitives so hard that the bridge was completely blocked up, numbers fell over its battlements, and others were bayoneted; in fact, we entered pell-mell with them. The town was set on fire in many parts by the enemy previous to our entering it, so that numbers of them, to avoid being bayoneted, rushed into the burning houses in their flight.

|

| The River Ancos forms a significant barrier |

Lieutenant Kincaid* passed with me through a gap in a hedge. We jumped from it at the same moment that a Portuguese Grenadier, who was following, received a cannon shot through his body and came tumbling after us. Very likely during the day a person might have a thousand much more narrow escapes of being made acquainted with the grand secret, but seeing the mangled body of a brave fellow so shockingly mutilated in an instant, stamps such impressions upon one's mind in a manner that time can never efface.

A man named Muckston laid hold of a French officer in the river and brought him out. He took his medal, and in the evening brought it to me. I took it, but should have felt happy to have returned it to the Frenchman.

|

| The road junction on the opposite bank at Point 3 with the high ground behind occupied by Marchand's division |

The enemy cannonaded our columns crossing the bridge and occasionally gave the skirmishers some discharges of grape. Notwithstanding, it did not deter us from following them and driving them some distance, when we were recalled and formed up. The British army bivouacked for the night. Lieutenants Chapman and Robert Beckwith wounded."

|

| The high-ground beyond the town was no doubt from where the French cannonaded the Allied columns mentioned by Simmons |

----------------------------------------------

*Lieutenant Kincaid, mentioned by Simmons in his account is non-other than Sir John Kincaid who wrote "Adventures in the Rifle Brigade" and "Random Shots by a Rifleman".

----------------------------------------------

Whilst Marshal Ney was doing his best to delay the Allies at Redinha, General Montbrun with his cavalry and a detachment of engineers had, since the 10th of March been reconnoitering the banks of the Mondego, finding the bridge blown and Trant's militia dug in with guns on the opposite bank, reporting to Massena that the town was held by the brigades of Trant and Silveira.

The actual force that opposed Montbrun was Trant's militia, 3,000 men with just six guns and under orders from Wellington to withdraw in the event of the French making a serious attempt to take the town.

By the 12th of March the position at Coimbra was hopeless as the Allied army was now too close to allow the French any time to occupy the town, build a replacement bridge and get 30,000 men across whilst Ney's rearguard attempted to hold back the Allied pursuit.

Thus Massena was forced to redirect the French route via Condeixa and Miranda de Corvo, bringing together the French army as a whole with the added pressure of so many French troops trying to use the same road.

|

| Captain Jean Marbot ADC to Marshal Massena |

The pressure on the French rearguard was constant and bitter with the cavalry on both sides engaging in small clashes along the route exemplified by the action described by Captain Marbot who was riding with a dispatch from Massena to Ney when he was challenged by a mounted infantry officer to single combat.

He at first ignored the challenge, but when accused by his adversary of cowardice, turned and rode towards him, only to be charged by two hussars who came out from some nearby woods in ambush. He recounted;

"I was caught in a trap, and understood that only a most energetic defence could save me... So I flew upon the English officer; we met; he gave me a slash across the face, I ran my sword into his throat. His blood spurted all over me, and the wretch fell from his horse to the ground, which he bit in his rage. Meanwhile the two hussars were hitting me all over..."

Even the French commander himself felt the pressure of the Allied pursuit, as he found himself and his staff threatened by Allied hussars (presumably KGL) after Ney having had his position turned at Codeixa and forced to retreat, forgot to inform Massena of his movement which was only countered by a robust stand by some French grenadiers and Massena's escort of dragoons.

Marbot recounted what happened;

"The English, never dreaming that the French commander would be thus separated from his army, took our group for a rear-guard, which they did not venture to attack; but it is certain that if the hussars had made a resolute charge, they would have carried off Massena and all who were with him."

|

| A portrait believed to be Henriette Leberton, the mistress of Marshal Massena, and wife of another officer, taken on campaign, dressed in hussar style uniform as an 'additional aid-de-camp' |

Needless to say, the relations between Ney and Massena were soured yet further after this incident with the latter revealing his own standards of honour for suspecting that Ney would have deliberately placed him and his mistress in danger, exclaiming several times according to Marbot;

"What a mistake I made bringing a woman to the war!"

Meanwhile Marshal Ney was forced to turn, yet again, at the hamlet of Casal Novo on the 14th of March, where Sir William Erskine was able to display his innate incompetence in handling the Light Division in front of the French rearguard on a rather foggy day; not believing the French to be present or to bother sending out a reconnaissance to check his assertion, leaving his troops exposed to heavy fire for two to three hours, before forcing their way into the village only to be met by a French line on the ridge behind and to suffer yet more unnecessary casualties before the French pulled away.

|

| The rearguard action at Casal Novo, the one place we didn't have time to visit. |

There is an excellent quote by Oman from William Napier's History recounting the conversation between Lieutenant Colonel John Ross of the 1/52nd Light Infantry and Erskine about the French rearguard and its position;

"... informed by Colonel Ross that the French were still in Casal Novo ' he kept blustering and swearing it was all nonsense—that the captains of the pickets knew nothing about the matter, and that there was not a man in the village. Just as he spoke the dense fog began to clear, and bang came a shot from a twelve pounder, which struck the head of our column and made a lane through it, killing and wounding many. Then came a regular cannonade, but the wise Sir William was sure it was but a single gun and a picket supporting it, and desired Colonel Ross to send my company against its flank .."

The needless losses suffered by the Light Division were small compensation for the fact that Wellington was now certain that the French had turned away from Coimbra and were now headed towards Mirand de Corvo and Foz d'Arouce beyond.

On the 15th of March the French rearguard again turned to face the Allied pursuit to hold the bridge over the River Ceira at the village of Foz d'Arouce.

Lieutenant George Simmons resumes the story;

"After marching a league from the latter town, we found the enemy's rear-guard had taken up a position at Foz de Aronce, with their back to the river Ceira, and the bridge behind them blown up. The remainder of their army was in position on the other side, having passed by fording, but in consequence of heavy rains, the river became so swollen that it was in a few hours impassable.

Our gallant chief observed with his penetrating eye the egregious mistake that the officer. Marshal Ney, who commanded the French rearguard, had made.

|

| Lieutenant Colonel Beckwith of the 95th Rifles now commanded the first brigade in the Light Division, consisting of the 43rd Light Infantry, 3rd Cacadores and four companies of the 95th Rifles |

We were all hungry and tired. I was frying some beef and anxiously watching the savoury morsel, when an order was given by Lord Wellington himself to Colonel Beckwith: "Fall in your battalion and attack the enemy; drive in their skirmishers, and I will turn their flank with the 3rd and 1st Divisions."

The whole Light Division were smartly engaged.

"The enemy opposed to the company (Captain Beckwith's) I was with, were behind a low wall. The approach was through a pine wood, and the branches were rattling about our ears from the enemy's bullets. Lieutenant Kincaid got shot through his cap, which grazed the top of his head. He fell as if a sledge hammer had hit him. However, he came to himself and soon rallied again. Lieutenant M'Cullock was shot through the shoulder. The attack commenced about five in the afternoon and lasted till after dark, the rain falling abundantly during part of the time.

The French fought very hard, and, some finding resistance to be in vain, threw themselves upon our generosity, but the greater part rushed into the river, which was tumbling along in its course most furiously, and there soon found a watery grave.

The enemy so little dreamt of being disturbed this night that their cooking utensils were left upon their fires for strangers to enjoy their contents. Such are the chances of war! I was quite exhausted and tired, and was with about fifteen of the company in the same state, when we made a great prize.

|

| The road junction at the edge of the village with the hill at its centre. The Light Division entered the village to the right of picture and 3rd Division along the road to the left. |

One of the men found a dozen pots upon a fire, the embers of which were low and caused the place to escape notice. Here we adjourned, and soon made the fire burn brightly. We found the different messes most savoury ones, and complimented the French for their knowledge of making savoury dishes, and many jokes were passed upon them.

The men looked about and found several knapsacks; they emptied them at the fireside to see their

contents and added to their own kits, shoes and shirts of better quality than their own. In every packet I observed twenty biscuits nicely rolled up or deposited in a bag; they were to last each man so many days, and he must, unless he got anything else, be his own commissary. We had been very ill-off for some days for bread, so that some of these proved a great luxury."

The next day 16th of March Simmons recorded in his diary;

"At two o'clock this morning the enemy had the arches of the bridge more effectually blown up. The weather began to clear at daylight. We saw numbers of the enemy dead in the river, and lying about near the bushes as the water had left them. It was judged about 700 or 800 had been drowned, and the 39th Regiment lost their Eagles in the water. A great quantity of baggage must have been destroyed or thrown into the water, as there were a great many mules and donkeys close to the river-side, hamstrung in the hind leg. These poor animals looked so wretched that one could not help feeling for them, and disgusted us with the barbarous cruelty of the French. To have killed and put them out of their misery at once would have been far better. We remained in bivouac."

|

| Just before the bridge is the old battle memorial, perhaps in situ when Sir Charles Oman walked the village on September 28th 1910 |

Oman's account of the action is the one I am most familiar with, with this little battle being one of the first Napoleonic actions I wargamed, back in my 'salad days';

"The 2nd and 8th Corps crossed the stream with much delay, at a bridge which had been somewhat injured by the local Ordenanca but was still serviceable. They deployed on a range of commanding heights on the further side, and encamped. Ney, always eager to carry on the detaining process which he had hitherto practised with such skill, only sent three of his six brigades across the river, though Massena had ordered him to pass, and to destroy the bridge.

He remained with the rest and Lamotte's light cavalry, posted on two long hills with the village of Foz between them, on the hither side of the water. Though he had a good position, yet the defile to the rear was a dangerous thing for such a large body of troops, since the Ceira was in flood, and every man had to retire over the single damaged bridge. Moreover the troops, tired by the night march, guarded themselves badly; in especial the cavalry, which ought to have watched every road, with vedettes out for many miles to the front, huddled together near the river for the convenience of water and grazing: General Lamotte indeed crossed the Ceira with great part of his men, and seems to have kept no look-out whatever."

|

| Nice to see the memorial has been updated to record the passing of the bi-centenary in 2011 |

"... Ney's rearguard visible on the lower eminences on the hither side of the stream. Picton and Erskine halted, thinking that it was too late in the afternoon to undertake a serious attack, and that Wellington would wait, as usual, for his supports to come up. They had directed their divisions to encamp and thrown out their pickets, when the Commander-in-Chief rode up, not long before dusk.

Surveying the enemy, and seeing that few battalions were under arms, and that Ney was evidently expecting no fighting—his cavalry indeed had given him no proper warning of the approach of the Allies—Wellington resolved to strike at once, though his nearest reserve, the 6th Division, was still some way off. Picton was told to attack the French left, the Light Division their right.

The first blow was very effective and partook of the nature of a surprise, for the enemy was caught unprepared. Some companies of the 95th Rifles, penetrating down a hollow road, arrived almost unopposed in the village of Foz, quite close to the bridge, while the rest of the Light Division was holding Marchand's troops engaged in a frontal fight, and Picton was making good way against the brigade belonging to Mermet, which formed the French left.

The noise of close combat breaking out almost in their rear, at a spot which seemed to indicate that the bridge was in danger, and their retreat cut off, caused a panic in the French right-centre, and the 39th regiment broke its ranks and hurried towards the bridge, where it met and became jammed against Lamotte's cavalry, who were hastily returning to take up the position from which they had unwisely retired an hour or two before.

Finding the passage impossible, the fugitives turned to a deep ford a little downstream and plunged into it, where many were drowned and the regimental eagle was lost *, while their colonel was taken prisoner.

|

| The bridge in a much better state than during the battle and showing what a significant river the Ceira is even when not in full spate. |

Ney saved the situation, which had arisen through his own disobedience to Massena's orders, by charging, with the third battalion of the 69th regiment the rifle companies which had got into Foz do Arouce and were threatening the bridge. They were driven back on to their support, the 52nd regiment, and the passage having been cleared by the Marshal's exertions, the troops to the left and right crossed it in some disorder, and took refuge on the opposite bank.

They were shelled during their defile, not only by Ross's and Bull's horse artillery batteries, but by some guns belonging to their own 8th Corps, which in the deepening twilight failed to distinguish between pursuers and pursued.

----------------------------------------------

*It was found in the river at low water and sent to London. The loss is mentioned in George Simmons's diary under March 16. Wellington sent it home in July.

----------------------------------------------

By the time that night had fully set in, the French rearguard was all over the river, and the bridge was blown up. If the attack had been delivered an hour earlier, it is probable that Ney would have suffered losses far greater than he actually endured—perhaps 250 men killed, wounded, drowned, or taken—for the British divisions were prevented by the failing light from acting as effectively as they otherwise might against the masses hastily recrossing the bridge.

Wellington's loss was trifling—4 officers and 67 men, nearly a third of them in the rifle companies which had broken the French centre for a moment, and had then been driven back by Ney.

The small remainder of the baggage of Marchand and Mermet was captured on this occasion, including some biscuit, which proved most grateful to the Light Division, as it had, like the rest of the British army, outmarched its transport."

The action at Foz d'Arouce marked a pause in the Allied pursuit, for not only were the French suffering in their lack of supplies and their inability to 'live off the land' in their usual rapacious ways but the Allies too were outrunning their supplies as mentioned by Simmons, with the Light Division only too happy to relieve the French of the meagre rations that they managed to capture from them.

|

| The Duke of Wellington was forced, through a lack of supplies for his Portuguese troops, to halt the Allied pursuit at Foz d'Arouce. |

Wellington wrote to the Earl of Liverpool after the action at Foz d'Arouce;

"The destruction of the bridge at Foz d'Arouce, the fatigue which the troops have undergone for several days, and the want of supplies, have induced me to halt the army this day... the Portuguese troops have no provisions, nor any means of conveying any to them... it is literally true, that Gen. Pack's brigade, and Col. Ashworth's had nothing to eat for four days, although constantly marching or engaged with the enemy. I was obliged either to direct the British Commissary Gen. to supply the Portuguese troops, or to see them perish from want; and the consequence is, that the supplies intended for the British troops are exhausted, and we must halt till more come up, which I hope will be this day."

Ney continued the withdrawal of VI Corps cautiously gaining time for the repairs to be made to the bridge ahead at Ponte de Murcella on the River Alva, before crossing under the cover of VIII Corps following in their wake and avoiding Allied attempts to cut his corps off now that the pursuit had been recommenced.

Supplies continued to be a problem for Wellington causing him to halt the pursuit on several occasions, noting on the 25th March that the French were pressing on towards the Coa, with their left looking likely to cross the river at Sabugal.

However what Wellington didn't know was that Massena had issued new orders to the Army of Portugal on the 22nd March that would surprise the Allies and the French. After a few days rest around Celorico, with the army expecting to march the last twenty miles to Almeida and a resupply, it was instead ordered to march south on Guarda and then on to Belmonte and Alfayates with the ultimate intent of crossing the Tagus and marching on Lisbon via the southern route.

Needless to say, the officers and men of his tired and ragged army received the news with shock and dismay, and Marshal Ney angrily refused to obey the order, explaining the needs of the army and complaining that;

"Since you always wait for the moment of greatest danger to make up your mind, I am obliged to prevent the total ruin of the army."

Massena removed Ney from command, instructing him to return to Spain to await the Emperor's pleasure, whilst Major Pelet was dispatched to Paris to make sure Napoleon was briefed with his side of the story.

|

| A contemporary picture of Sabugal and its castle overlooking the River Coa. |

Massena then pressed on with his ridiculous plan, stopping at Guarda and sending out reconnaissance patrols to the south to find that the land ahead was barren, as he had been told to expect by his commanders; in addition, D'Erlon had refused to follow him with IX Corps, instead marching to Almeida, and writing to inform Massena that the town only had enough supplies for fifteen days and that Ciudad Rodrigo was in a similar state.

With his army short of supplies, ammunition and horses whilst also exhausted and underfed, Massena finally saw sense and abandoned his plans, turning instead to get the army behind the River Coa.

The Allies had finally resumed their stop-start pursuit and entered Guarda just as the French were leaving, with Reynier's II Corps bringing up the rear with his corps reaching Sabugal on the 2nd April 1811, with Massena urging him to resume his march as soon as possible.

Reynier, however, decided to halt and wait for darkness to cover his retreat, most likely influenced by the lack of French cavalry, with the exhausted remnants sent away to Ciudad Rodrigo, to refit and take up remounts to make up their losses.

Wellington's situation was markedly different, now having been reinforced with new troops from Lisbon together with the arrival of the newly created 7th Division, amounting to some 6,000 men, the Allied commander felt emboldened to strike, now he knew from his cavalry patrols that the enemy was standing firm upon the Coa at Sabugal.

To quote Oman;

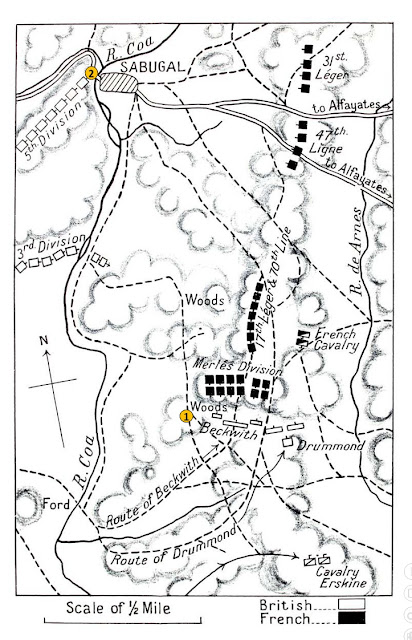

"The plan which Wellington evolved for the final eviction of the French from Portugal was to turn their left wing on the side of Sabugal, while containing their right wing (the 6th Corps) on the central Coa.

Sabugal, a little walled place with a ruined Moorish castle, lies in a projecting bend or hook of the Coa, which turns back just above the town at right angles to its original course, which is directly from east to west. The river is not far from its source, and though its banks are steep its waters are narrow, and there are many fords both above and below Sabugal. If a strong turning column, concealing itself in the hills, passed along the south bank of the Coa, and crossed the river some miles above the town, it could throw itself upon the rear of the 2nd Corps and cut it off from its retreat on Alfayates.

Meanwhile a general attack by Wellington's main body would drive it from its position straight into the arms of the turning column, and there would be a good chance of inflicting a crushing defeat upon the corps, perhaps of capturing it wholesale. If the attack were delivered by surprise at dawn, the whole matter ought to be completed before either the 6th or the 8th Corps could get up to the support of Reynier. When at last they could appear on the field, the 2nd Corps would be already demolished, and Wellington was prepared to risk a general action.

|

| The view from Point 1 towards Sabugal and the castle poking up above the line of trees following the course of the River Coa. The 3rd Division would have forded the Coa off to the left of picture |

The turning column was to be formed by the Light Division and the two cavalry brigades, who were to ford the Coa at two separate points two and three miles respectively above Sabugal. Meanwhile the enemy was to be given no chance of falling upon this detachment, since he was to be attacked in front with very superior forces. Picton and his division were to cross an easy ford a mile south of Sabugal, the 5th Division was to assail the town-bridge at the same moment. It was intended that the turning force should cross the Coa first, but only so far ahead of the frontal attacking force as to make it certain that it should not get engaged with the main body of the enemy, before the 3rd and 5th Divisions were coming into action.

Unfortunately the morning of the 3rd of April was one of dense fog—good for concealing the march of the troops, but bad in that it prevented the troops from discovering their objective. Both Picton and Dunlop (who was commanding the 5th Division in Leith's absence on leave) resolved not to move, and sent to Wellington, who was hard by, for orders.

|

| Looking back from Point 1 towards the Coa from where the Light Division crossed |

Not so the rash and presumptuous Erskine, who repeated this day the precise mistake that he had made at Casal Novo three weeks back. Without coming himself to the front, he sent an aide-de-camp to the Light Division, to bid it descend to the river and cross at the ford which had been assigned to it in the general scheme. The cavalry were also ordered to move forward and take the other ford, more to the right, by which they were to get into the enemy's rear.

|

| The end of the French held ridge, occupied by Merle's division, as it would have been seen by Beckwith's brigade and with Drummond's brigade attacking further to the right of picture. |

The Light Division, and Beckwith's brigade in particular, now unsupported, pressed on over the Coa and launched itself into the attack on the French held ridge, driving the enemy back but finding themselves hard-pressed as more French troops came up in support of those they had already engaged; leaving Beckwith's brigade in disorder and with French cavalry threatening Drummond's brigade out on the right flank who having ignored Erskine's order to hold, and had marched to the sound of the guns in support of Beckwith.

Erskine, who had attached himself to the light cavalry brigade, contrived to lose himself and the brigade in the fog, whilst also losing a lone squadron of the 16th Light Dragoons that came up to help drive off the French cavalry threatening Drummond's brigade's right flank.

Oman picks up the story;

"At this moment the fog suddenly lifted, and both Wellington and Reynier were able to make out the face of the battle. The sight was not altogether comforting to either of them: Wellington could see the Light Division on the crest, opposed by a very superior enemy (the proportion was about five to three at this moment) and with their left flank turned by the column which had just come up. Reynier, on the other hand, saw the masses of Picton's and Dunlop's divisions halted close above the fords, at and below Sabugal, and just preparing to cross. He had so stripped his centre and right, while bringing up troops to crush the Light Division, that only the two regiments forming Heudelet's 1st Brigade, the eight weak battalions of the 31st Leger and 47th Ligne, about 3,300 bayonets, were left to occupy two miles of slope on each side of the town of Sabugal.

|

| Fine groves of large chestnut trees, although these looked like oaks, on the approach march of Beckwith's brigade as it turned the French line seen at Point 1. |

This brigade was thereby exposed to grave danger, for while it was doing its best to 'contain' the Light Division, Picton, coming up from the river at a furious pace, with the 5th Fusiliers deployed in his front, rushed in upon its flank, and drove its battalions one upon another. The 17th and 70th were overwhelmed and thrust down the back of the hill with a loss of 400 men, of whom 120 were unwounded prisoners. Their wrecks took refuge with the other brigades, which retired as rapidly as they could along the Alfayates road, with the 31st Leger and 47th Ligne, the only intact body, covering the flight of the rest.

|

| The 31e Legere in Spain in 1811-12 by Boisselier, part of Arnauld's brigade, Heudelet's division at Sabugal. Note the officer wearing Spanish brown cloth as a make-shift replacement tunic. |

......the rain, which had been falling for almost the whole morning, became absolutely torrential, and hid the face of the country-side so thoroughly that Wellington commanded the whole army to halt. It is said that this order was given on the false intelligence that the 8th Corps was visible coming up from Alfayates to join Reynier, a report for which there was no foundation whatever.

Erskine and the cavalry never touched the retreating force, save one squadron of the German hussars, who happed upon the French transport column, and captured the private baggage of Reynier himself and General Pierre Soult.

The total loss of the French was 61 officers and 689 men; this fearful proportion of losses in the commissioned ranks was due to the gallantry with which they threw away their lives in bringing up to the front the shaken and demoralized soldiers, who could not face the English musketry. One gun and 186 unwounded prisoners were taken.

The British loss was only 169—that of their Portuguese companions no more than 10. Of the total of 179 no less than 143 were men of the Light Division, of whom 80 belonged to the 43rd; Picton's troops, only engaged for a few minutes at the end of the combat, had twenty-five casualties. The horse artillery lost one, the German hussars two men wounded. It is sufficiently clear from these figures who had done the fighting that day"

|

| Slightly on from Point 1 the crossing point of 3rd Division from the treeline along the Coa to the left of picture |

Lieutenant Simmons account records the progress of the Light Division as it made its way across the Coa and the battle they had with Merle's division on the ridge. Considering all the issues described by Oman, you just have to admire the 'matter of fact' account of what was a very hard battle for Simmons and his comrades, mentioning casually that the Allied cavalry was 'unlucky', certainly unlucky to be attached to General Erskine!

"Colonel Beckwith's Brigade crossed the river Coa; the sides steep; the 95th led. It was deep and came up to my arm-pits. The officer commanding the French piquet ordered his men to fire a few shots and retire. On getting footing, we moved up in skirmishing order and followed in the track of the piquet.

|

| Sabugal castle sits above the bridge used by 5th Division |

We were met by a regiment, and kept skirmishing until the rest of the Brigade came up, when we pushed the enemy through some fine groves of large chestnut-trees upon the main body (Reynier's Corps or 2nd). Two guns opened on us and fired several discharges of round and grape. The guns were repeatedly charged, but the enemy were so strong that we were obliged to retire a little. Three columns of the enemy moved forward with drums beating and the officers dancing like madmen with their hats frequently hoisted upon their swords. Our men kept up a terrible fire. They went back a little, and we followed. This was done several times, when we were reinforced by the other Brigades, and the guns were taken.

|

| Some of the locals out and about enjoying the afternoon sunshine down by the Coa |

But from the enemy's numbers being very much superior, the combat was kept up very warmly until General Picton's (3rd) Division came up and pushed out its Light companies on their flank, the 5th Regiment forming a line in support.

The 5th Division, under General Dunlop, soon crossed at this bridge and passed through Sabugal.

The enemy gave way and went off in confusion; the rain now fell in torrents and materially assisted their retreat.

|

| The bridge over the Coa at Point 2, taken by 5th Division following the Alfayates road |

Our cavalry was unluckily too distant to take advantage of the loose manner in which they moved off.

The Light Division was put into the town for the night, as a compliment for its conduct on this day, and the remainder of the army in bivouac. Lieutenant Arbuthnot was killed, Lieutenant Haggup wounded. Colonel Beckwith wounded and his horse shot.

|

| The River Coa, described by Oman as having steep banks and narrow waters at this part of its course, although still quite deep according to Simmons, coming up to his armpits when he forded it. |

Lieutenant Kincaid and I, with our baggage, were provided with a dilapidated habitation. We had very little to eat, but were sheltered from the pelting rain.

In one corner of the place several miserable human beings were huddled together, nearly starved to death. I gave a poor little child some of my bread, but then all the wretched creatures began to beg from me. I could not assist them, not having enough to satisfy the cravings of a hungry stomach, and being aware of another rapid march awaiting me, and more exertions and dangers to encounter before we could put the French over the frontiers of Portugal; and as Sancho says, 'It is the belly that keeps up the heart, not the heart the belly.'"

"The Portuguese nation are informed that the cruel enemy who had invaded Portugal, and had devastated their country, have been obliged to evacuate it, after suffering great losses, and have retired across the Agueda. The inhabitants of the country are therefore at liberty to return to their occupations."

Now back to the Portuguese border with Spain, Carolyn and I were looking forward to heading south, just as Massena had planned to do, with the Tagus valley and warmer weather to look forward to, but first we would take time to conclude Marshal Massena's campaign into Portugal; with his last throw of the dice at Fuentes de Onoro, a battle that Wellington never claimed as a victory, even though he was left in possession of the field at the end of it.

References referred to in this post:

The Key to Lisbon, The Third Invasion of Portugal 1810-11 - Kenton White

Wellington Against Massena, The Third Invasion of Portugal 1810-11 - David Buttery

History of the Peninsular War Vol IV - Sir Charles Oman

Fantastic post - thank you for such an enthralling account

ReplyDeleteHi David,

DeleteMany thanks, I'm really pleased you enjoyed the read and appreciate your comment.

JJ

This series of posts on your blog is fantastic - I look forward to more even though I'm catching up with your progress now I'm back from my holidays... During which I visited York Army Museum, largely as a result of having seen it on your blog.

ReplyDeleteHi and thank you.

DeleteIt's really great to hear back when others have enjoyed reading particular posts and even better when it inspires visits to the places covered.

Cheers

JJ

Thanks for this great tour, JJ, especially of Sabugal. I am flushing out a scenario and as always, your blog is a terrific resource!

ReplyDeleteHi Bill,

DeleteThanks for your comment, it prompted me to take another look at this post myself and brought back a lot of happy memories.

Great, consider me now looking forward to your next AAR.

JJ